| Contents | Previous | Next |

Five studies have documented that 60 to 90 percent of patients with panic disorder develop a major depression at some time in their lives (Breier et al. 1984; Cloninger et al. 1981; Raskin et al. 1982; Pariser et al. 1979; Katon et al. 1986). Conversely, Leckman and colleagues (1983&) found that 21 percent of patients with major depression had a past or current episode of panic disorder. Data from the ECA project also revealed that people with major depression were 19 times more likely to have panic disorder and 15 times more likely to have agoraphobia than people without major depression (Boyd et al. 1984). Patients with panic disorder or agoraphobia and a history of major depression have been shown to have a more severe anxiety disorder, greater levels of past impairment, and a longer duration of panic disorder when compared to patients with panic disorder or agoraphobia and no history of depression (Breier et al. 1984). Leckman and colleagues (1983&) demonstrated that patients with major depression who also suffered from panic disorder had increased family prevalence of depression, anxiety disorders, and alcoholism.

Several studies have documented that major depression is not only a secondary complication of panic disorder, but frequently occurs autonomously (Breier et al. 1984; Katon et al. 1986). In one epidemiologic study of panic disorder in primary care, 44 percent of patients with panic disorder had an episode of major depression prior to their episode of panic disorder, 33 percent had an episode of panic disorder prior to an episode of major depression, and 22 percent had simultaneously occurring episodes (Katon et al. 1986).

Panic disorder and major depression clearly tend to occur in the same patient population, but it is not clear whether these two disorders have the same underlying etiology. Breier and colleagues (1984) offered two possible hypotheses: (1) anxiety and depressive symptoms are different phenotypic expressions of a shared genetic diathesis or (2) the presence of one disorder might lead to the development of a second disorder with a different pathophysiologic state (e.g., diabetes mellitus often leads to the development of coronary artery disease).

The data suggesting an overlap of panic disorder and major depression is supported by Goldberg's (1979) finding that 67 percent of patients with mental illness in primary care clinics had mixed symptoms of anxiety and depression. Thus, any primary care patient with symptoms of anxiety should be carefully screened for major depression and vice versa. The frequent co-occurrence of these disorders suggests that antidepressant medication (tricyclics or MAOIs) will be needed and that dosage levels used to treat depression should be employed. Specific psychotherapies (cognitive-behavioral) that increase the patient's confidence in coping with this severe anxiety disorder may also decrease panic attacks and secondary depressive symptoms (Rapee and Barlow 1988).

Research on panic disorder by Quitkin and colleagues (1972) demonstrated that patients with panic disorder often tended to self-medicate with sedative-hypnotic agents, especially alcohol and benzodiazepines. As panic disorder worsens, the patient frequently develops severe social phobias that interfere with social and vocational functioning. Also, the patient often develops generalized anxiety and not only suffers from the severe acute episodes of panic, but also from chronic symptoms of free-floating anxiety. Alcohol or sedative-hypnotics are sometimes used in desperation to try to control the anxiety. These agents usually have a short anxiolytic action, but the rapid drop in blood levels may then cause an exacerbation of severe anxiety and worsening panic attacks. Alcohol, in particular, may also worsen a psychophysiologic disorder, such as peptic ulcer disease or labile hypertension, that was precipitated by the panic disorder.

Panic Disorder and Secondary Alcohol AbuseMr. M was a 35-year-old laboratory technician who developed acute anxiety attacks with symptoms of tachycardia, shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating or diaphoresis, and a fear of impending death several weeks after his woman friend broke off their relationship; They had lived |!| together for 3 years and had had recurrent relationship problems for the last year. Mr. M developed severe social phobias that prohibited participation in group meetings of his research group and eating in the hospital cafeteria. He began to drink the grain alcohol from his laboratory prior to research meetings to try to decrease his anxiety, soon escalating the dosage and also drinking wine at night to help with sleep. He presented to his family physician with hemetemesis and melena approximately 3 months after the start of the panic attacks and 2 months after escalating his drinking. He was admitted to the impatient service with a hematocrit of 20. He received several blood transfusions and was found on endoscopy to have had a large bleed from a gastric ulcer. He was quite tremulous, with increased pulse and blood pressure for 3 to 4 days, necessitating 25 mg of librium TID initially. He was seen in psychiatric consultation and diagnosed as having panic disorder and secondary alcohol abuse. He gave no past history of either psychiatric problem prior to the current episode. After 14 days of sobriety, Mr. M was still having frequent anxiety attacks and severe social anxiety. He was started on imipramine 25 mg with dosages increased to 100 mg over 10 days, made a rapid recovery, and was well on 2-year follow-up. |

Alternatively, primary alcohol abuse and recurrent withdrawal may lead to a kindling effect on central controls of the sympathetic nervous system and the subsequent onset or worsening of panic disorder (Post et al. 1984). Kindling is the opposite of toleranceŚwith increasing exposure to a drug, the person experiences more intense effects rather than decreased effects. Thus, repetitive decreases in alcohol blood levels may increase the arousal and responsivity of the sympathetic nervous system. As seen in exhibit 5, many of the symptoms of panic disorder and alcohol withdrawal are quite similar and, therefore, may present difficulty in differential diagnosis (George et al. 1988).

Exhibit 5. Overlap of symptoms of panic disorder and alcohol withdrawal |

|

| Panic disorder | Early alcohol withdrawal |

| Tachycardia Chest pain Dyspnea Sweating Hot and cold flashes Dizziness Tremulousness/shaking Paresthesia Faintness Nausea or gastrointestinal distress Derealization or depersonalization Fear of loss of control, dying, or going crazy |

Tachycardia Tremulousness Hypertension* Sweating Diarrhea Nightmares* Nausea, vomiting, or gastrointestinal distress Cramps Exaggerated startle Fever* Agitation, restlessness* |

| *Starred items either occur more commonly in alcohol withdrawal or only in alcohol withdrawal (nightmares, fever, and agitation). | |

The ECA study determined that 13 percent of Americans met criteria for alcohol abuse at some time in their lives (Robins et al. 1984). Exhibit 6 lists the DSM-III-R criteria (APA 1987) for psychoactive substance dependence. The main feature of this disorder is that the person has impaired control of psychoactive substances (such as alcohol) and continues to use the substance despite adverse consequences to health, vocation, family, and social life. Some people never meet criteria for dependence on alcohol or other substances, but they have maladaptive patterns of use. These maladaptive patterns include recurrent use of alcohol when it is physically hazardous (when driving or using machinery) or continued use of alcohol despite recurrent social, vocational, or physical problems resulting from it. These types of maladaptive patterns without dependence are labeled psychoactive substance abuse.

For both females and males, the prevalence of drinking is highest and abstention is lowest in the, 21- to 34-year age range. Alcohol abuse or dependence has three main patterns. The first consists of regular daily intake of large amounts; the second, of regular heavy drinking limited to weekends; and the third, of long periods of sobriety interspersed with binges of heavy daily drinking lasting for weeks or months (APA 1987). Alcohol abuse and dependence are often associated with abuse of other substances, including marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, heroine, and sedativehypnotics. The use of alcohol and these other substances together is most often seen in adolescents and adults under age 30. Although benzodiazepines are contraindicated in alcohol abuse, they are often prescribed by physicians in a misguided attempt to try to help stop or reduce the patient's craving for alcohol.

Exhibit 6. Diagnostic criteria for psychoactive substance dependence |

|||||||||||||

| A | At least three of the following:

Note: The following items may not apply to cannabis, hallucinogens, or phencyclidine (PCP):

|

||||||||||||

| B | Some symptoms of the disturbance have persisted for at least 1 month, or have occurred repeatedly over a longer period of time. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Source: Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition, Revised. Copyright 1987 American Psychiatric Association, p. 252-253. | |||||||||||||

Three recent studies of patients with alcohol abuse found that up to a third of them suffer from panic disorder, agoraphobia, or multiple social phobias (Mullaney and Tripett 1979; Bowen et al. 1984; Smail et al. 1984). Helzer and Pryzbeck (1988) have also shown that patients diagnosed as meeting criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence in the ECA study were more than twice as likely to suffer from panic disorder.

Small and colleagues (1984) studied the co-occurrence of these disorders in depth to try to discern which problem occurred first and whether alcohol use ameliorated or worsened social phobias and panic attacks. They studied 60 alcohol abusers and found that 21 subjects had mild phobias and 11 had severe phobias. The more severely phobic males were also found to be the most alcohol dependent, and those with no phobias were least alcohol dependent. This effect was not found in females. All phobic alcoholics reported that alcohol had helped them cope in feared situations, and almost all had deliberately used it for this purpose.

In a subsequent study of 24 hospitalized alcohol abusers with panic disorder and multiple social phobias, periods of heavy drinking and dependence on alcohol were associated with an exacerbation of agoraphobia and social phobias (Stockwell et al. 1984). Subsequent periods of abstinence were associated with substantial improvements in these anxiety states. Thus, although alcohol was often used to try to cope with panic attacks and social phobias, it paradoxically made these anxiety disorders worse as alcohol abuse became more severe. The authors hypothesized that the worsening of phobias resulted from the repeated avoidance of fear through drinking and the increased anxiety from rapidly fluctuating blood levels of alcohol.

The implications of this research for the primary care physician is that all patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobias, and generalized anxiety should be carefully screened for alcohol and other psychoactive substance abuse. If alcohol abuse and/or other psychoactive substance abuse is present, that disorder should be treated first and the patient reassessed after detoxification and alcohol treatment. If panic attacks and social phobias are still present, treatment with a tricyclic antidepressant and/or behavioral therapy may be instituted. On the other hand, all patients with primary alcoholism should be questioned about panic disorder, agoraphobia, and social phobias. If these disorders co-occur with alcoholism, the patient should be reassessed after detoxification and alcohol treatment. If these disorders are not alleviated with alcohol treatment alone, specific psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic measures should be instituted.

Patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) have unrealistic or excessive worry about one or more life circumstances for 6 months or longer during which they are bothered more days than not by these concerns (exhibit 7). The patient must also have at least 6 of 18 symptoms from three categories:(1) motor tension, (2) autonomic hyperactivity, and (3) vigilance and scanning. In some patients, symptoms of GAD are lifelong and persistent, whereas for other patients, the symptoms are acute, intermittent, and closely related to stressful life events.

Exhibit 7. Diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder |

|

| A | Unrealistic or excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation) about two or more life circumstances, e.g., worry about possible misfortune to one's child (who is in no danger) and worry about finances (for no good reason), for a period of 6 months or longer, during which the person has been bothered more days than not by these concerns. In children and adolescents, this may take the form of anxiety and worry about academic, athletic, and social performance. |

| B | If another Axis I disorder is present, the focus of the anxiety and worry in A is unrelated to it, e.g., the anxiety or worry is not about having a panic attack (as in panic disorder), being embarrassed in public (as in social phobia), being contaminated (as in obsessive compulsive disorder), or gaining weight (as in anorexia nervosa). |

| C | The disturbance does not occur only during the course of a mood disorder or a psychotic disorder. |

| D | At least 6 of the following 18 symptoms are often present

when anxious (do not include symptoms present only during panic attacks): Motor tension

Autonomic hyperactivity

Vigilance and scanning

|

| E | It cannot be established that an organic factor initiated and maintained the disturbance, e.g., hyperthyroidism, caffeine intoxication. |

| Source: Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition, Revised. Copyright 1987 American Psychiatric Association, p. 252-253. | |

In primary care, the majority of patients with symptoms of GAD develop these symptoms secondary to another major DSM-III-R disorder, most commonly panic disorder, major depression, or alcohol abuse (Breslau and Davis 1985; Katon et al. 1987&). These three disorders must be actively screened for and ruled out along with organic causes of anxiety (see chapter 8). This will leave only a small group of patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Recent research suggests that many of these GAD patients actually do have infrequent panic attacks (Barlow et al. 1986; Katon et al. 1987b) and, similar to patients with panic disorder, may respond better, especially over the course of several months, to tricyclic antidepressants than standard benzodiazepines (Johnstone et al. 1980; Kahn et al. 1986). Other proven psychopharmacologic agents for GAD include benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, and buspirone (Roy-Byrne and Katon 1987).

The central feature of social phobia is a persistent fear of, and compelling desire to avoid, a situation in which the individual is exposed to public scrutiny and may act in a way that will be humiliating and embarrassing (APA 1987). Examples include being unable to urinate in a public lavatory, hand trembling when writing in the presence of others, and saying foolish things or not being able to answer questions in social situations. To fit this diagnosis, the patient must not only fear social situations, but actually avoid them or endure them with intense anxiety. These avoidant behaviors interfere with social or occupational functioning and the patient has marked distress about being afraid. Other DSM-III-R disorders, such as panic disorder or major depression, must be ruled out, and the fear must be unrelated to symptoms that are actually caused by a medical disorder (e.g., trembling or tremor in benign essential tremor). One of the few studies of treatment of social phobias (Roy-Byrne and Katon 1987) reported convincing evidence of the superiority of MAOIs in 70 percent of cases and suggested that beta-blockers were no better than placebos. No reports of tricyclic antidepressant efficacy have been published. Exposure-based behavioral treatments (reviewed in chapter 10) have been reported to be successful (Heimberg et al. 1985).

Simple phobia refers to a persistent fear of and compelling desire to avoid a circumscribed stimuli (object or situation) other than fear of having a panic attack (panic disorder) or humiliation or embarrassment in certain social situations (as in social phobia) (APA 1987). Also, the phobic stimulus must be unrelated to the content of the obsessions in obsessive compulsive disorder or the trauma of posttraumatic stress disorder. The person recognizes the fear as excessive or unreasonable, but nonetheless avoids the situation or endures it with intense anxiety. Exposure to the object (dog, cat, snake) or to the situation (heights, closed-in spaces) invariably brings on intense anxiety, and the avoidance interferes with the patient's life.

Systematic desensitization and in vivo exposure are the most effective treatments for the simple phobias, and no real benefit has ever been shown from medications (Roy-Byrne and Katon 1987).

The DSM-III-R criteria (APA 1987) for PTSD are presented in exhibit 8. Patients with PTSD have experienced a severe catastrophic event that is outside the range of normal human experience and would be distressing to anyone. The patient frequently and persistently reexperiences the event by having recurrent, often intrusive images of the trauma; recurrent dreams or nightmares of the event; suddenly acting or feeling as if the traumatic event were reoccurring, including illusions, hallucinations, or flashback episodes; and intense psychologic distress when exposed to environmental stimuli that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event. Patients with PTSD have persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma or numbing of general responsiveness, as well as chronic symptoms of increased arousal when exposed to events that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event. Recent research has suggested that patients with PTSD have increased autonomic nervous system tone. Vietnam veterans with PTSD were found to have chronic elevation of noradrenergic activity compared with veterans having other psychiatric diagnoses (Kosten et al. 1987). Kolb (1984) also showed that combat veterans with PTSD had greater autonomic nervous system arousal in response to an audio-tape of battle sounds than did combat veterans without the disorder.

Panic disorder is also believed to be secondary to dyscontrol of the central alarm system of the brain that controls the autonomic nervous system, and researchers have reported strong links between panic disorder and PTSD. Mellman and Davis (1985) found that 25 of 25 Vietnam veterans with PTSD reported that their flashbacks occurred during anxiety states meeting DSM-III criteria for panic attacks. Rainey and colleagues (1987) administered infusions of sodium lactate (which cause panic in approximately 70 percent of panic attack patients versus less than 5 percent of controls) to seven patients with PTSD, six of whom also met criteria for panic disorder. The lactate infusions resulted in flashbacks in all seven patients and panic attacks in six patients.

If there is a connection between PTSD and panic disorder, then medications that are effective in dampening autonomic nervous system tone in panic disorder should be effective in PTSD. Recent reports suggest that both imipramine and MAOIs are effective in PTSD (Bleich et al. 1986), and Kolb and associates (1984) demonstrated that clonidine, an alpha-2 receptor agonist that diminishes release of norepinephrine, has also been effective in reducing the autonomic hyperactivity of PTSD.

Exhibit 8. Diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder |

|

| A | The person has experienced an event that is outside the range of usual human experience and that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone, e.g., serious threat to one's life or physical integrity; serious threat or harm to one's children, spouse, or other close relatives and friends; sudden destruction of one's home or community; or seeing another person who has recently been, or is being, seriously injured or killed as the result of an accident or physical violence. |

| B | The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in at least one of

the following ways:

|

| C | Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma or numbing of

general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by at

least three of the following:

|

| D | Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not present before the

trauma), as indicated by at least two of the following:

|

| E | Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in B, C, and D of at least 1 month. Specify delayed onset if the onset of symptoms was at least 6 months after the trauma. |

| Source: Reprinted with permission from The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition, Revised. Copyright 1987 American Psychiatric Association, p. 250-251. | |

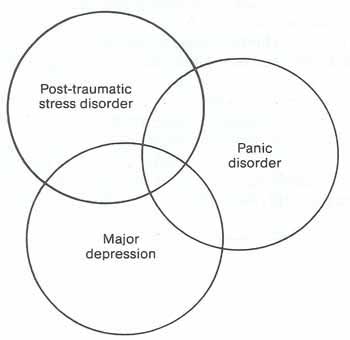

In primary care, civilian cases of PTSD are occasionally seen, and these patients may have combinations of symptoms of PTSD, panic disorder, and major depression (figure 2). These cases are often precipitated by extreme trauma such as a severe automobile accident, industrial accident, or natural disaster (flood, hurricane, fire). Many of these cases are complicated by the legal and disability systems that may unconsciously lead to prolongation of disability. Early intervention with accurate diagnosis and aggressive treatment is essential to avoid the risk of long-term disability.

| Figure 2. Relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder to panic disorder and major depression |

|

|

The following case demonstrates the overlap between PTSD, panic disorder and major depression and the reinforcement of maladaptive illness behavior by the disability system.

Posttraumatic Stress DisorderMrs. R was a 38-year-old mother of two employed as a food service worker in a local hospital. Her problems started when she wheeled her food service cart into an elevator that malfunctioned and fell two floors. Mrs. R fell down striking her head and neck and was unconscious for an undetermined amount of time. The elevator lights went out when it malfunctioned, and she was trapped inside for 1 to 2 hours while an elevator maintenance crew worked to get her out. She was hospitalized for several days, and a neurologic evaluation including CT head scan, skull x rays, and spinal films proved negative. After the accident, she developed chronic neck and head pain as well as nightmares of the incident and daytime intrusive memories and flashbacks. She felt she could never go back to work at the same hospital because of severe anxiety associated with even passing the building. She refused to use elevators because of severe anxiety and wondered if she could ever do the same type of work again. She complained of insomnia, decreased energy, irritability and depressed mood, anhedonia, poor concentration, and poor appetite since the accident. In addition, she developed acute attacks of rapid heartbeat, diaphoresis, dyspnea, dizziness, paresthesia, and a sense of impending doom. These attacks were very frightening to her and made her fearful of going out alone. Her husband complained that she was detached from him and the children since the accident and was ignoring most of her household duties. The patient was diagnosed as having PTSD, panic disorder, and major depression. She was started on imipramine, 50mg daily, with dosage increasing to 250mg over 2 to 3 weeks. Most of her symptoms improved rapidly on this medication, but she still felt she could never return to her old job and eventually was given 50-perent disability retirement in a legal settlement. |