| Contents | Previous | Next |

The patient with panic disorder has cognitive, affective, and somatic symptoms (table 1) and also suffers social consequences such as increased dependency on the spouse and vocational problems (Grant et al. 1983). In primary care, patients with panic disorder often selectively focus on and complain about the most frightening autonomic somatic symptom or on a psychophysiologic symptom caused by autonomic hyperactivity (e.g., diarrhea, epigastric pain, headache) (Katon 1984). Freud (1894) recognized the many modes of presentation of anxiety attacks and the frequent misperception by patients that they had a primary physical illness when he stated "the proportion in which somatic symptoms are mixed in anxiety attacks varies to a remarkable degree, and almost every accompanying symptom alone can constitute the attack just as well as anxiety itself." Panic disorder may also cause an exacerbation of symptoms from chronic medical illnesses such as asthma, angina pectoris, and diabetes (Katon and Roy-Byrne 1989).

In a study of 55 primary care patients with panic disorder referred for psychiatric consultation by their primary care physicians, Katon (1984) found that 89 percent of the patients had initially presented with one or two somatic complaints and that misdiagnosis often continued for months or years. The three most common complaints were of cardiac symptoms (chest pain, tachycardia, irregular heart beat), gastrointestinal symptoms (especially epigastric distress), and neurologic symptoms (headache, dizziness, vertigo, syncope, or paresthesias). Clancy and Noyes (1976) also provided evidence for somatization in panic disorder. They examined the medical clinic records of 71 patients with anxiety neurosis and found that 30 different categories of tests had been carried out. A total of 358 tests and procedures were performed on the group (range 0-11; mean = 7.5 tests), and these patients had 135 specialty consultations. The most frequently requested tests were electrocardiograms (38 percent), electro-encephalograms (24 percent), and upper gastrointestinal series (25 percent); the most commonly requested specialty consultations were from the cardiology, neurology, and gastroenterology services. These results document the frequency of cardiac, neurologic, and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with panic disorder.

|

Table 1. Components of panic disorder |

|||

| Cognitive | Affective | Somatic | Social |

| Worry Sense of foreboding Sense of impending doom or dread Exaggeration of innocuous situations as dangerous Exaggeration of probability of harm in specific situations Tendency to be inattentive, distractible Sense of unreality Rumination Loss of control |

Anxiety or nervousness Secondary depression Irritability |

Tachycardia Hyperventilation (patient complains of shortness of breath) Tingling in hands and feet Diaphoresis Dizziness or syncope Flushing Muscle tension Tremulousness Restlessness Chest tightness, pressure on chest (pseudoangina) Headaches, backaches, muscle spasms |

Dependency Vocational limitations Isolation |

| Source: Adapted from Grant et al. 1983,p. 909. | |||

Lydiard and colleagues (1986) recently described a series of patient who had both irritable abowel syndrome (IBS) and panic disorder. IBS is a chronic gastrointestinal syndrome characterized by abdominal discomfort and pain with an alteration in bowel habits (cramping, diarrhea, constipation) in the absence of weight loss or demonstrable gastrointestinal pathology. Effective treatment of panic disorder also ameliorated the patients’ irritable bowel complaints. Several patients with both irritable bowel disorder an panic disorder were also described by Katon (1984).

Irritable bowel syndrome affects 8 to 17 percent of the general population (Drossman et al. 1982) and several studies have found that 70 to 90 percent of IBS patients have diagnosable psychiatric problems, most commonly anxiety and depression (Young et al. 1976). Drossman and colleagues (in press) compared 73 IBS patients who received medical care for their symptoms to 82 persons with IBS who did not seek such care. The IBS patients visiting physicians had higher scores on psychologic tests of depression, anxiety, and somatization. The following case demonstrates the association of irritable bowel symptoms with panic disorder and the amelioration of both the anxiety and the irritable bowel disorder with a tricyclic antidepressant.

Panic Disorder Associated With Irritable Bowel SyndromeMrs. S is a 47 year – old teacher who presented to the primary care physician with left lower quadrant “crampy” pain and intermittent diarrhea and constipation. She had several prior gastrointestinal workups, resulting in negative upper and lower GI series and colonoscopy. Mrs. S Stated that her bowel tended to act up under stress and had been an intermittent problem to her throughout her life. She was referred to psychiatric consultation owing to her apparent nervousness. Mrs. S gave a history of having suffered from five episodes of major depression. At the interview, she had depressed mood, but no other vegetative symptoms. She complained of episodes of rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, sweatiness, dizziness, and a sense of loss of control that often preceded her abdominal pain and diarrhea. Her family physician had treated her with an anticholinergic agent for her bowel symptoms without success. The patient was diagnosed as having current panic attacks as well as a history of major depressive episodes. She was started on 25 mg of imipramine with the suggestion to increase by 25 mg imipramine with the suggestion to increase by 25 mg increments every 5 days. On 50 mg of imipramine, her abdominal symptoms and panic attacks disappeared, and she remained asymptomatic over the succeeding year. |

The presentation of cardiac complaints by patients with panic disorder is especially likely to lead to expensive and potentially iatrogenic medical testing. Past studies have documented high anxiety and depression scores on psycho-logic tests of patients who had chest pain and normal coronary angiograms (Elias et al. 1982; Costa et al. 1985). Followup studies of these patients have consistently shown that the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction is low (Kemp et al. 1986), yet 50 to 75 percent have persistent complaints of chest pain and disability after normal coronary arteriograms (Ockene et al. 1980). These patients are frequently described in the medical literature as "cardiac neurotics" or "cardiac cripples" (Caughey 1939).

Three recent studies found that patients with chest pain who had negative angiography or treadmill tests had a very high prevalence of panic disorder (Katon et al. 1988; Beitman et al. 1987; Bass and Wade 1984). Bass and Wade (1984) examined 99 patients with chest pain undergoing coronary arteriog-raphy. Fortysix had hemodynamically insignificant disease, and 53 had significant coronary stenosis. Twenty-eight (61 percent) of the patients with insignificant disease had psychiatric diagnoses compared to 23 percent of those with significant obstruction. The most common psychiatric diagnosis in the patients with insignificant disease was anxiety neurosis, and 52 percent of this patient group exhibited polyphobic behavior.

Katon and colleagues (1988a) studied 74 patients with chest pain who were referred to coronary angiography. Using structured interviews, 43 percent of the 28 patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries were found to have panic disorder compared to 5 percent of 46 patients with chest pain who had significant coronary artery stenosis. Patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries had a significantly higher mean number of autonomic symptoms (tachycardia, dyspnea, dizziness) associated with their chest pain (5.2 versus -> 3.8, p<.05) and were significantly more likely to have atypical chest pain. Beitman and colleagues (1987) found that 43 (58 percent) of 74 patients with atypical or nonanginal chest pain and no evidence of coronary artery disease by electrocardiogram, treadmill, or angiography had panic disorder.

Ford (1987) reviewed the association between chest pain and psychiatric illness in the ECA study and found that 2.5 percent of patients complained of chest pain. Patients with chest pain were four times as likely to have panic disorder, three times as likely to have phobic disorder, and twice as likely to have major depression as controls without chest pain.

The above correlations documenting a high association between chest pain and panic disorder have more significant implications for the primary care physician than for the cardiologist. The cardiologist is more likely to be sent patients with multiple cardiac risk factors and to feel bound to refer them for cardiac testing. On the other hand, the most common primary care patient is a 20- to 40-year-old female, the subgroup with the highest prevalence rate for panic disorder (Myers et al. 1984) and a low frequency of coronary artery disease.

In all three of the above studies of patients with chest pain referred for cardiac testing, patients with negative workups were significantly younger and more likely to be female. Moreover, 40 percent of primary care patients with panic disorder present with chest pain (Katon 1984). Primary care physicians are the "filter" for cardiac referrals, and thus increased education about the association between chest pain and panic disorder may increase the accuracy of diagnosis and decrease unnecessary medical referrals and testing. The following case demonstrates the expensive and extensive testing that some patients with panic disorder receive.

Panic Disorder Associated With Chest Pain and Other Somatic ComplaintsMr. D was a 35 year-old lawyer who presented to his primary care physician with acute episodes of chest pain, tachycardia, and labile hypertension. After these spells, he often had a had a sensation of stomach tightness and headaches. He was initially hospitalized in the CCU for 3 days where cardiac enzymes, EKG, echocardiogram, and exercise tolerance testing were all negative He was next referred to a gastroenterologist. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, gastroscopy, serum amylase, and liver function tests revealed only a small duodenal ulcer. He was started on cimetadirie with no improvement of his symptoms. The patient was next referred to a neurologist. A CT head scan, EEG, EMG (for tingling in the hands), lumbar puncture, and neurologic examination were all negative. The patient was then referred to an endocrinologist for the episodic labile hypertension. A workup for pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, hypoglycemia, and thyroid disease were all negative. Finally, the patient was referred for psychiatric consultation because of his apparent nervousness and his wife's concern over his increasing depression. On psychiatric examination, he described the attacks of chest pain as not only accompanied by tachycardia but also by shortness of breath, tingling in hands and feet, diaphoresis, dizziness, and a sense of impending doom. In addition, he complained of depressed mood, insomnia, and decreased appetite, libido, and concentration. He was diagnosed as having panic disorder and major depression and Started on imipramine, with a gradually increasing dosage to 300 mg daily at bedtime. He had a rapid recovery over a 1- month period with complete resolution of his symptoms. His labile hypertension resolved and his propranolol and cimetadine were tapered and discontinued over a 1-month period |

In primary care, three main types of somatization are seen (Rosen et al. 1982). The first and most common type occurs when patients present with somatic complaints after one or more stressful life events. Many of these somatic complaints are psychophysiologic in origin, such as headaches, epigastric distress, muscle spasms, and insomnia. They are probably secondary to the autonomic nervous system arousal associated with stress. The second type of somatization is subacute and occurs when patients suffering from major depression and panic disorder selectively focus on the somatic components of these illnesses or on a psychophysiologic problem (headaches, dizziness, chest pain) precipitated by these illnesses.

The third and most difficult type of somatization to handle is chronic somatization. These patients frequently have chronic psychologic pain secondary to developmental insults such as being abandoned, physically and/or sexually abused, or severely neglected in their families of origin (Zoccolillo and Cloninger 1986; Walker et al. 1988). Their families were often chaotic, and alcohol and drug abuse were common (Woerner and Guze 1968). Drug and alcohol abuse have often been problems for these patients as well (Perley and Guze 1962). Frequently, this group of patients suffers from a sense of powerlessness in interpersonal relationships, and somatic symptoms become a mechanism for adapting to a threatening world. Somatic symptoms can be used to manipulate a spouse, avoid intimacy, and attain disability payments and prescription medications (opiates and benzodiazepines) (Katon et al. 1984).

Patients with chronic somatization may also suffer from panic disorder and/or major depression. The major developmental insults they have experienced should leave them prone to these affective problems. However, treatment of panic attacks or depression in this group of patients often leads to only 30- to 40-percent improvement in symptoms. Somatization often persists because of the benefits within the social support network that continue to reinforce illness behavior. Personality disorders are often associated with chronic somatization and, as reviewed above, personality disorders are a predictor of poor treatment response in patients with panic disorder.

It is important to emphasize that untreated patients with panic disorder frequently develop multiple complaints in multiple organ systems, and they can be misdiagnosed as suffering from chronic somatization or hypochondriasis, in general, or more specifically, somatization disorder (Katon 1986; Noyes et al. 1986). Pharmacologic studies of panic disorder have consistently demonstrated extremely high scores on psychologic measures of somatization (such as the somatization scale of the SCL-90) in patients with panic disorder and a reduction in their scores to normal levels with effective treatment (Sheehan et al. 1980; Noyes et al. 1986; Fava et al. 1988). Noyes and colleagues (1986) examined the hypochondriacal tendencies seen in patients with panic disorder. They found that, prior to treatment, patients with panic disorder scored as high on an index of hypochondriasis, the Illness Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ) (Pilowsky and Spence 1983), as did a group of hypochondriacal psychiatric patients. After treatment, patients with panic disorder had a significant reduction in somatic preoccupation, disease phobia, and disease conviction as measured by the IBQ. These data suggest that the majority of patients with panic disorder who present as hypochondriacs with a myriad of somatic symptoms can be effectively treated.

Katon (1984) studied 55 patients meeting DSM-III criteria for panic disorder who were referred to psychiatric consultation. Two-thirds of the female patients and one-third of the male patients had multiple positive symptoms on the medical review of symptoms and, as a result, spuriously met DSM-III criteria for somatization disorder (which require 14 or more medically unexplained somatic symptoms in females and 12 or more symptoms in males). In a later epidemiologic study of panic disorder in primary care using the DIS interview, Katon and colleagues (1986) determined that patients with panic disorder averaged 14.1 symptoms on a medical review of systems compared to 7.3 symptoms in a control group (p<.005).

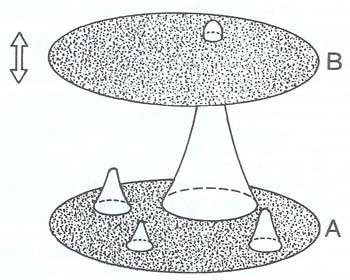

The above studies indicated that panic disorder seems to lower the conscious threshold for worrying about physical symptoms — patients focus more on their bodies. Also, by the nature of autonomic nervous system arousal, panic disorder is apt to cause physical symptoms. Robinson and Granfield (1986) published a schematic model to help explain how emotional upset leads to the increased perception of somatic symptoms (figure 1).

| Figure 1. A model of symptoms |

|

|

| Source: Adapted from Robinson, J.O., and Granfield, A.J. The frequent consulter in primary medical care. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 30:587-600, 1986. Copyright 1986 by Pergamon Press. Reproduced with permission. |

In this model, A represents a state of total comfort that rarely occurs physiologically. Diary studies of patients have shown that the average patient has a new symptom every 5 to 7 days, few of which are brought to the attention of a physician (Demers et al. 1980). Discomfort experiences that are sub-threshold physiologic events stemming from internal organs, joints, muscles, and so forth are represented by bumps on surface A. The height of the bump represents the seriousness of the experience in terms of its becoming consciously perceptible. During the emotional arousal of severe anxiety, surface A becomes increasingly bumpy, leading to psychophysiologic symptoms such as insomnia, headache, epigastric distress, and fatigue.

Surface B represents the threshold above which discomfort is consciously perceived. This surface is driven up or down by mood states, anxiety, stress, and focus of attention. Studies of patients with panic disorder or major depression suggest that these two illnesses tend to lower the B surface, leading to increased focusing, monitoring, and worrying about physical symptoms (Katon 1984; Katon et al. 1986; Katon and Von Korff in press). The result of both the increased physiologic symptoms and bumpiness of the B axis and the increased focus and worry about these symptoms on the A axis is that the patient with an illness like panic disorder becomes anxious and obsessed by his symptoms and appears to the primary care physician to have hypochondriasis or somatization disorder. The danger is that the primary care physician, who sees many "trait" somatizers, will misperceive this as a trait or long-term irreversible part of the patient's personality. It is instead "state" somatization, which is subacute and directly resulting from panic disorder, and it is highly curable given accurate diagnosis and specific treatment.

The NIMH ECA study pointed to the difficulty that psychiatrists also have in distinguishing state or secondary somatization, resulting from an acute psychiatric illness such as panic disorder or major depression, from trait or primary somatization, a largely irreversible condition (Boyd et al. 1984). The data from this large psychiatric epidemiologic survey of five American cities demonstrated that patients who met DSM-III criteria for somatization disorder were 96 times more likely to also meet criteria for panic disorder than were patients who did not meet criteria for somatization disorder. Liskow and colleagues (1986) found that 41 percent of 78 female psychiatric outpatients with somatization disorder also met criteria for panic disorder. Similarly, Sheehan and Sheehan (1982) found that 71 percent of patients who met criteria for panic disorder also met criteria for somatization disorder.

One of the problems in differentiating these two illnesses is that symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, and dizziness are part of the DSM-III-R criteria (APA 1987) for both disorders (exhibit 4). Also, one of the major criteria for the diagnosis of somatization disorder is an increased tendency to report physical symptoms that cannot be well explained medically. As mentioned above, research suggests that patients with panic disorder may report twice as many physical symptoms as do controls without psychiatric disorder.

How can the primary care physician proceed with diagnosis when faced with an obviously hypochondriacal patient with multiple unexplained physical symptoms? One differentiating factor is that somatization disorder usually begins in the late teens and is chronic; the hypochondriacal preoccupation of these patients is only part of the generally chaotic lives these patients lead. The family histories of patients with somatization disorder often reveal a tendency for females in the family to have somatization disorder and the males to have antisocial personality disorders and/or be alcohol abusers (Woerner and Guze 1968). Developmentally, patients with somatization disorder usually were brought up in chaotic families where they experienced physical and/or sexual abuse, neglect, and abandonment (Zoccolillo and Cloninger 1986). Their adult relationships are often characterized by multiple marriages and relationships that are abusive (e.g., the spouse is an alcoholic who is frequently violent) (Guze 1976). In addition, patients with somatization disorder have a tendency to abuse prescription medications (opiates and general sedative-hypnotics), street drugs, and alcohol (Perley and Guze 1962).

Exhibit 4. Diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder |

|

| A | A history of many physical complaints or a belief that one is sickly, beginning before the age of 30 and persisting for several years. |

| B | At least 13 symptoms from the list below. To count a symptom

as significant, the following criteria must be met:

|

Symptom List:Gastrointestinal symptoms:

Pain symptoms:

Cardiopulmonary symptoms:

Conversion or pseudoneurologic symptoms:

Sexual symptoms for the major part of the person's life after opportunities for sexual activity:

Female reproductive symptoms judged by the person to occur more frequently or severely than in most women:

|

|

| Source: Reprinted with permission from the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition,

Revised. Copyright 1987 American Psychiatric Association, p. 263-264. * The starred items may be used to screen for the disorder. The presence of two or more of these items suggests a high likelihood of the disorder. |

|

Even though the above characteristics often help distinguish patients with somatization disorder from those with panic disorder, accurate diagnoses are not always clear. Many patients with panic disorder are not accurately diagnosed and may go several years with their illness, often chronically somatizing. In a psychopharmacologic trial, Sheehan and colleagues (1980) found that patients with panic disorder had visited a mean of 10 prior physicians for their symptoms before an accurate diagnosis of panic disorder was made and specific treatment initiated.

When the etiology of chronic somatization is unclear, the following rationale should be used. Since somatization disorder is a chronic severe condition with no known specific treatment and panic disorder is highly treatable, patients with multiple unexplained somatic symptoms should be carefully screened for panic disorder (as well as major depression). If the patient meets DSM-III criteria for both somatization disorder and panic disorder, then the physician should err in favor of the diagnosis of panic disorder and a pharmacologic trial should be instituted.