| Contents | Previous | Next |

Guideline: Once major depressive disorder is diagnosed, intervention that predictably decrease symptoms and morbidity earlier than would occur naturally in the course of the illness are logically tried first. The key initial objectives of treatment, in order of priority, are (1) to reduce and ultimately to remove all signs and symptoms of the depressive syndrome, (2) to restore occupational and psychosocial function to that of the asymptomatic state, and (3) to reduce the likelihood of relapse and recurrence. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

Acute treatment refers to formally defined procedures used to reduce symptoms and restore psychosocial function. All treatments are administered in the context of clinical management, which refers to the education of and discussion with patients (and families, when appropriate) about the nature of depression, its course, and the relative costs and benefits of treatment options. Clinical management is distinct from supportive therapy, which itself is a “formal” therapy or which can be combined with medication. Supportive therapy goes beyond clinical management and focuses on the management and resolution of current difficulties and life decisions through the use of the patient’s strengths and available resources. In some milder, less chronic, nonrecurrent, nonpsychotic cases, an extended evaluation (one or two additional visits), when clinically safe, may help to differentiate those with major depression that requires formal treatment from those with depressive symptoms (not major depression) that may resolve with only time, support, explanation, and reassurance.

The certainty of treatment response is weighed against the likelihood and severity of potential adverse treatment effects. Treatment selection is based on an evaluation of the potential benefits and harms of each alternative. Second- and third-line treatments are considered if first-line treatments are contraindicated, ineffective, or inappropriate in particular cases.

The optimal treatment is highly acceptable to patients, predictably effective, and associated with minimal adverse effects. It results in the complete removal of symptoms and the restoration of psychosocial and occupational functioning. Potential adverse effects include:

Effective treatment results in symptom remission; improved interpersonal, marital, and occupational functioning (DiMascio, Weissman, Prusoff, et al., 1979; Wells, 1985); reduced potential for suicide; reduction in excess health care utilization and cost (McDonnell-Douglas, 1989, 1990); as well as reduced disability from concurrent general medical conditions and improved long-term outcome (van Korff, Ormel, Katon, et al., 1992).

Formal treatments for major depressive disorder fall into four broad domains: medication, psychotherapy, the combination of medication and psychotherapy, and ECT. (Light therapy is also a treatment option for mild to moderate seasonal depressions.) Each domain has benefits and risks that must be weighed carefully in the selection of a treatment option for a given patient.

Medications have several clear benefits. They are easy to administer; are effective in mild, moderate, and severe forms of major depressive disorder; and require little patient time. Medications also have some disadvantages:

Side effects from antidepressants range from relatively minor, annoying, but fairly frequent, problems (e.g., dry mouth or constipation) to more significant, but less frequent, side effects (e.g., orthostatic hypotension) to substantial side effects (e.g., cardiovascular conduction abnormalities with classic tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs]). Most side effects are dose-dependent, requiring dosage adjustments in many cases. For most patients, the benefits of treatment far outweigh the risks.

The advantages of psychotherapy are:

Although psychotherapy does not have the physiologic side effects found with medications, unrecognized disadvantages may occur when psychotherapy is chosen as the sole therapy:

Although the routine use of both medication and a formal psychotherapy is not recommended as the initial treatment for most patients, panel consensus, logic, and some research suggest that combined treatment may be specifically useful in the following instances:

In these cases, the advantages of combined treatment may include a higher probability of response, a greater degree of response for individual patients, or a lower attrition rate from treatment

The disadvantages of combined treatment include the disadvantages of each alone. Those patients with milder, transient depressions may not require, respond to, or be able to tolerate medication. Those whose illness would have remitted with medication plus clinical management would have spent unnecessary time and money for a formal psychotherapy. Moreover, if the depression recurs, both treatments may again be indicated, since it will be unclear whether one alone would have been sufficient. There is no evidence, however, that the combination of medications and psychotherapy has a worse outcome than either treatment alone (see Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming).

Because of its proven efficacy in severely symptomatic patients who have failed to respond to one or more medication trials, ECT has an important role in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Electroconvulsive therapy is appropriate for patients with severe and/or psychotic depressions who have not responded to other forms of treatment or who have serious general medical conditions and severe depression for which ECT may be safer than medication. Although hospitalization is indicated for acutely suicidal or dangerously delusional patients, some practitioners believe that ECT results in more rapid resolution of these lifethreatening features than does medication. However, ECT should be considered cautiously and used only after consultation with a psychiatrist, because ECT:

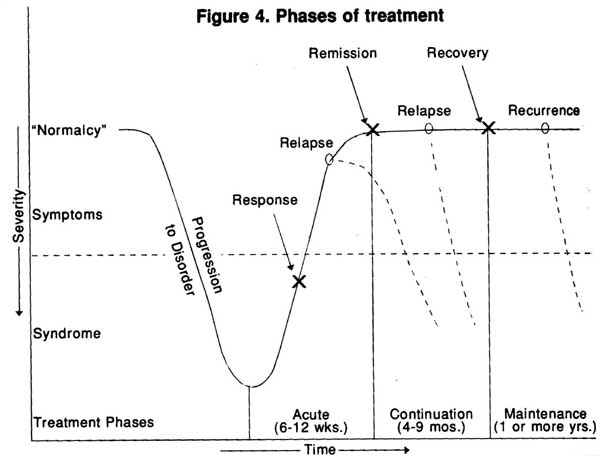

Treatment for major depressive disorder may include three phases: acute, continuation, and maintenance. The overall aim of all three phases is the attainment of a stable, fully asymptomatic state and full restoration of psychosocial function (a remission). Acute treatment aims at removing all depressive symptoms. If the patient improves with treatment, a response is declared. A remission may occur either spontaneously or with treatment. If the symptoms return and are severe enough to meet syndromal criteria within 6 months following remission, a relapse (return of symptoms of the current episode) is declared. Continuation treatment aims at preventing this relapse. Once the patient is asymptomatic for at least 6 months following an episode, recovery from the episode is declared. At recovery, continuation treatment may be stopped. For those with recurrent depressions, however, a new episode (recurrence) may occur months or years later. Maintenance treatment aims at preventing a recurrence. Recurrences are expected in 50 percent of cases within 2 years after continuation treatment (NIMH, 1985). For well established, recurrent depressions, the rate may approach 75 percent (Frank, Kupfer, Perel, et al., 1990).

Figure 4 illustrates the phases of treatment and the possible course of a depressive episode (Kupfer, 1991). The initially symptomatic patient begins to develop symptoms that ultimately (in days, weeks, or months) increase in number and severity until the full syndrome of major depressive disorder is present. It is useful to conceptualize treatment as having three phases (Frank, Prien, Jarrett, et al., 1991) because:

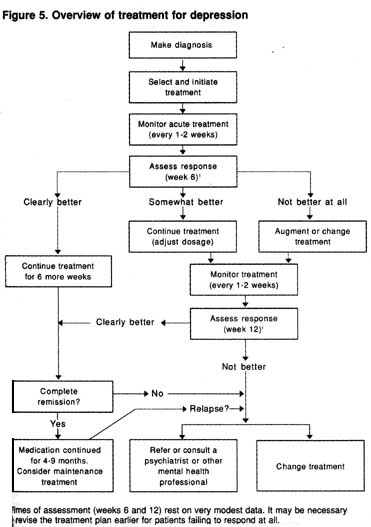

It is reasonably well established that patients who have only a partial response to acute treatment will have more symptoms during continuation treatment. Furtherwell as recurrence once treatment is discontinued (Prien and Kupfer, 1986). Figure 5 offers a schematic overview of treatment for depression.

Figure4. Phases of treatment

For virtually all patients, practitioner who provides the medication (or other treatment) also provides support, advice, reassurance and hope as well as side-effect monitoring (including vital signs for those on medication), and dosage adjustments. This “clinical management” is exceptionally important, especially with depressed patients whose pessimism, low motivation and energy, and sense of social isolation or guilt may lead them to give up, not adhere to treatment, or even to drop out of treatment.

Guideline: A depressed outpatient’s adherence to treatment can be improved by educating the patient and, in many cases, the family about the treatment its potential side effects, a nd its likelihood of success. (Strength of Evidence-A.)

Adherence to treatment is a significant problem in the management of all patients, whether they have clinical depressions or other medical conditions. Compliance rates have been estimated from as low as 4 percent to as high as 90 percent in patients with mood disorders, depending on the methods of assessment (e.g., blood drug concentrations, pill counts, number of appointments kept). Adherence includes following prescribed activities, such as keeping appointments, taking medication, and completing assignments. Adherence can be evaluated directly by interviewing the patient.

Figure 5. Overview of treatment for depression

1 Times of assessment (weeks 6 and 12) rest on very modest data. It may be necessary to revise the treatment plan earlier for patients failing to respond at all.

In depressed patients, the presence of a personality disorder or concurrent substance abuse, a patient’s lack of acceptance of the diagnosis or treatment plan, and troublesome treatment side effects are all associated with poorer treatment compliance (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). Variables not consistently correlated with adherence include age, education, marital status, employment status, socioeconomic status, intelligence, gender, social adjustment, and life events.

At least seven studies have found that patient education helps to ensure treatment adherence in depressed outpatients (Altamura and Mauri, 1985; Anderson, Griffin, Rossi,et al., 1986; Myers and Calvert, 1984; Peet and Harvey, 1991; Seltzer, Roncari, and Garfinkel, 1980; van Gent and Zwart, 1991; Youssel, 1983). For this reason, clinical management for all depressed patients, regardless of the type of treatment that they receive, should include patient and, where appropriate, family education about depression. Appropriate information includes descriptions of:

It is helpful for the practitioner to give patients explicit instructions, offer them an opportunity to ask questions and discuss common difficulties in complying with the proposed treatment, and encourage them to report problems with adherence (Goodwin and Jamison, 1990). Information exchange can be enhanced by providing patients with educational materials. For some, one or two extra appointments designed specifically to provide information are useful. Practitioners may sometimes find it advisable to educate others in the patient’s life (e.g., employers, spouses, children, licensing authorities), with the patient’s permission, as well. Patients taking medication may initially need particularly close follow-up to ensure adherence, assess symptom response, minimize side effects, and find the optimal medication dosage. Medications that can be taken once daily may be preferable, as better adherence has been shown with once-aday regimens than with medications that require multiple daily doses.

While it is essential that all patients be provided with information about their disorder and its treatment, the practitioner may want to consider specific adherence counseling for patients who demonstrate:

A variety of useful educational materials are available from the D/ART (Depression/Awareness, Recognition, Treatment) Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (NlMH). Other organizations that provide support and information include the National Depressive and ManicDepressive Association, the National Alliance for the Mentally ill, the National Mental Health Association, and the National Foundation for Depressive illness. Many diverse self-help groups are also available. These support groups provide an accepting, caring environment for people who share similar problems and life experiences. It is important, however, that patients with formal mood syndromes not rely solely on self-help as treatment for their conditions, since no data support the efficacy of such groups as sole ‘`treatments.” In fact, most of these groups provide medical information to patients, often assisting practitioners and patients with adherence problems, especially over the longer term.

The initial evaluation includes asking the patient about the nine criterion symptoms of a major depressive episode, as well as the current level of interpersonal and occupational functioning. In addition to the clinical interview, patient self-report or clinician symptom-rating scales may permit a rapid assessment of the nature and severity of depressive symptoms. interviewing a spouse or close friend about the patient’s day-today functioning and specific symptoms is also helpful in determining the course of the illness, current symptoms, and level of functioning.

Follow-up visits during acute treatment are used to evaluate the level of symptom relief and restoration of function. Symptom evaluation (whether by interview alone or combined with the use of a symptom-rating scale) allows both practitioner and patient to assess response to treatment, determine whether the medication dosage should be adjusted, and clarify whether and when alternative treatments are needed.

Guideline: A 4- to 6-week trial of medication or a 6- to 8-week trial of psychotherapy usually results in at least a partial remission (50 percent symptom reduction), and a 10- to 12-week trial usually results in a nearly full response (minimal or no symptoms) to treatment. However, full restoration of psychosocial function often takes longer. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

Once selected, the initial treatment should be applied for a sufficient length of time to allow a reasonable assessment of the patient’s response. Switching treatment too early provides no benefit, inappropriately discourages the patient, or leads to an erroneous conclusion that the treatment is ineffective. On the other hand, persisting over a prolonged period without any response is costly in pain and suffering and may unnecessarily prolong the episode.

The basis for this guideline rests on a careful review of 528 randomized controlled trials of medication (Table 4, page 47) and the 46 randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy (Table 11, page 75) in adult and geriatric out patients (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). A partial response at 6 weeks may indicate the need for further medication dosage adjustments or a longer trial of the same treatment (i.e., medication, psychotherapy, or the combination, see pages 113-115). After 12 weeks, a partial response suggests the need for adjunctive psychotherapy, adjunctive medication, a switch to a different treatment, or consultation/referral.

Guideline: If a patient shows a partial response to treatment by 5 to 6 weeks, the same treatment is continued for S or 6 more weeks. (Strength of Evidence = A.) If the patient does not respond at all by 6 weeks or responds only partially by 12 weeks, it is appropriate to consider other treatment options. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

There are insufficient randomized controlled trials with medication, psychotherapy, or the combination to provide a scientifically sound basis for any conclusion about the “next best step” if the initial treatment is ineffective or only partially successful. However, it is well-known that patients differ from one another in the timing of treatment response (2 to 8 weeks for medication, 2 to 12 weeks for psychotherapy); therefore, a partial response by 5 to 6 weeks suggests that it is appropriate to continue the same treatment for 5 to 6 more weeks (optimizing dosage when medication is used). If the patient does not respond by 6 weeks or only partially responds by 12 weeks, the practitioner should consider the options of seeking consultation or referral, switching treatments altogether, or adding a second treatment to the first.

If the initial treatment is an antidepressant medication, there is evidence from sequential open trials to indicate that both partial responders and nonresponders will benefit from either adding a second medication to the first or augmenting or switching to a different medication class (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). Switching or augmenting medications is an option for nonresponders at 6 weeks or for partial responders at 12 weeks.

If psychotherapy alone is the initial treatment and it produces no response by 6 weeks or only a partial response by 12 weeks, clinical experience and logic suggest a trial of medication, given the strong evidence for the specific efficacy of medication. The advisability of continuing formal psychotherapy in these situations has not been studied. However, some trials reveal that a subset of patients who are not responding to psychotherapy by 6 weeks will do so by 12 weeks (Elkin, Shea, Watkins, et al., 1989).

If the initial acute treatment is combined treatment (antidepressant medication administered optimally and formal psychotherapy) and it produces no response by 6 weeks, switching to another medication is a strong consideration. For some patients, especially those who have had previous medication trials, medication augmentation may be preferable to switching. For partial responders to the combination at week 12, no clear-cut data for the next best step are available, although logic and efficacy data indicate that augmenting or switching medication; reasonable options (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming).

| Contents | Previous | Next |