| Contents | Previous | Next |

Up to one in eight individuals may require treatment for depression during their lifetimes; up to 70 percent of psychiatric hospitalizations are associated with mood disorders (Secunda, Katz, Friedman, et al., 1973). The direct costs of treatment for major depressive disorder, combined with the indirect costs from lost productivity, are significant. According to one study based on a 1980 population base, the total number of cases of major depressive disorder among those aged 18 or older in a 6-month period would be 4.8 million; in addition, 60 percent of suicides could be attributed to major depressive disorder (Stoudemire, Frank, Hedemark, et al., 1986). This translates to more than 16,000 suicides or 7 deaths per 100,000 annually. In 1980, mood disorders accounted for more than 565,000 hospital admissions, 7.4 million hospital days, and 13 million physician visits annually. Office-based psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ costs were $453 million, pharmaceutical costs were $138 million, the cost of home and institutional care was $141 million, and total direct costs were more than $2.1 billion. Indirect morbidity costs were estimated to be $10 billion; total mortality costs due to lost productivity, $4 billion. The total cost of mood disorders to society was roughly $16 billion.

Patients with major depressive disorder experience substantial pain; suffering; and psychological, social, and occupational disability during the depression (Johnson, Weissman, and Klerman, 1992; von Korff, Ormel, Katon, et al., 1992; Wells, Golding, and Burnam, 1988a,b). If depressive conditions accompany selected nonpsychiatric medical conditions (e.g., coronary artery disease, diabetes), the outcome of these concurrent general medical disorders is likely to be worse than if depression were not present (Carney, Rich, Freedland, et al., 1988; Carney, Rich, teVelde, et al., 1987a,b; Keitner, Ryan, Miller, et al., 1991; Lustman, Amado, and Wetzel, 1983; Lustman, Griffith, and Clouse, 1988; Lustman, Griffith, Clouse, et al., 1986).

In addition to economic costs, depression can carry great personal costs because of the social stigma associated with the diagnosis and treatment of a “mental illness.” This stigma likely plays a large role in patients’ reluctance to seek, accept, adhere to, and continue treatment. Evidence compatible with the notion of stigma includes the following:

As a result of stigma, depressed patients often incorrectly believe that they have caused their own illness or are solely responsible for its cure. They fear (sometimes correctly) subsequent discrimination in hiring, promotion, and other occupational opportunities. It is logical to infer that until depression is dealt with on an equal footing with nonpsychiatric medical disorders (attitudinally, economically, socially, occupationally, and politically), it will be underreported and national health statistics will likely remain misleading.

Given this stigmatization, it is vital to educate patients (and their families, if appropriate) about the nature, prognosis, and treatment of depression to increase adherence to treatment, relieve unnecessary guilt, and raise hope. Patients need to know the full range of suitable treatment options before agreeing to participate in treatment.

This Clinical Practice Guideline was developed with support from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) by the Depression Guideline Panel to assist both patients and primary care providers (e.g., general practitioners, family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, physician assistants, and others) in the treatment of major depressive disorder. The general principles embodied in these guidelines should also provide a framework for others who treat depressed persons. A detailed description of the development of these guidelines is found in Depression in Primary Care: Volume 1. Detection and Diagnosis (AHCPR Publication No. 93-0550, 1993) and in Chapter 1 of the Depression Guideline Report (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming).

These guidelines are not intended to render selected procedures reimbursable or not reimbursable. That decision logically falls to third-party payors. Likewise, the guidelines do not specify which professionals should conduct which procedures, an issue addressed by licensing/privileging bodies. Should the recommended steps in the treatment of depression fall outside the expertise of the practitioner or be impractical, given constraints of time or availability of appropriate resources, the practitioner should consult with, or refer the patient to, someone knowledgeable in these matters.

This Clinical Practice Guideline is an abbreviated version of a far larger document, the Depression Guideline Report, to which the reader may refer for further detail. These treatment guidelines focus on outpatients with major depressive disorder, particularly those seen in primary care settings. They do not address the treatment of children or adolescents, bipolar disorder, or depressive symptoms insufficient to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. The panel members believe that the steps and procedures proposed here form a reasonable general treatment plan in many cases; they have attempted to be as explicit as possible in making recommendations, such as how often to see a patient, when to increase a medication dosage, and when to change to a different treatment. However, the treatment of an individual patient requires adaptation of both the general (strategic) and specific (tactical) recommendations to suit the patient’s particular situation.

The guidelines are based on systematic reviews of the available scientific literature. The reviews commissioned involved a comprehensive examination of literature published through December 1990. However, articles published after this date were included when they provided information that would otherwise have been unavailable. The panel chose to focus on randomized controlled trials as the highest level of credible evidence for treatment efficacy for two major reasons. First, many non-mental health care practitioners and many in the general public are not fully aware of the striking evidence for the efficacy of various treatments. Second, the statements derived from such evidence can be made with substantial certainty. Where evidence is either lacking or incomplete, this is noted; in these cases, either no guideline has been derived or options are provided, based on logical inference, available data, and panel consensus. When the evidence is reasonably clear though modest in amount, these findings are noted, and a tentative recommendation is offered. Thus, the guidelines that follow are coded according to the strength of the available evidence as interpreted by the panel:

| A | Good research-based evidence, with some panel opinion, to support theguideline statement. |

| B | Fair research-based evidence, with substantial panel opinion, to support the guideline statement. |

| C | Guideline statement based primarily on panel opinion, with minimal research-based evidence, but significant clinical experience. |

The full guideline development process is illustrated in Figure 1

Figure 1. Guideline development process

|

Topic chosen by AHCPR ↓ Panel chair chosen by AHCPR ↓ Panel members recommended by the chair and AHCPR ↓ Panel members approved/appointed by AHCPR ↓ Panel convened and focus for literature reviews refined ↓ 21 diagnostic and 18 treatment topics selected for review ↓ Literature reviewers for specific topics selected by panel ↓ NLM literature searches conducted using key words selected for each topic by panel/reviewers with MEDLINE and Psychiatric Abstracts for each topic ↓ Abstracts received by literature reviewers ↓ Abstracts reviewed for inclusion/exclusion criteria by literature reviewers ↓ Full copy of each article selected read by literature reviewers ↓ Literature review and evidence tables created by literature reviewers ↓ Review read/critiqued by panel chair, methodologist, and a minimum of 3 panel members ↓ Reviews revised where indicated

↓ Relevant parts of each review abstracted by panel for Depression Guideline Report ↓ Depression Guideline Report drafted by panel ↓ All reviews independently reviewed by all panel members and 14 scientific reviewers ↓ Depression Guideline Report revised ↓ Depression Guideline Report synopsized to Clinical Practice Guideline, A Patient's Guide, and Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians ↓ Peer review requested from 73 organizations and 14 new scientific reviewers, pilot review of A Patient's Guide, Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians, and Clinical Practice Guideline in nine sites ↓ Critiques from peer/pilot review considered by panel ↓ All versions of guidelines reviewed by panel ↓ Final copy of all versions of guidelines submitted to AHCPR |

In applying these guidelines, several caveats are in order. First, the reader should not confuse the absence of studies with the absence of efficacy. In certain situations, there is little direct evidence for the efficacy of various treatments, based on randomized controlled trials (for example, with patients who have major depressive disorder and concurrent general medical conditions). Furthermore, several commonly used treatments, such as supportive psychotherapy, have not been subjected to randomized controlled trials. In the absence of evidence, no scientifically based statement about the efficacy of a treatment can be made. However, case reports, case series, clinical experience, and logical inference form a basis for selecting treatments for particular patients.

Second, the primary care practitioner is cautioned not to persist with extensive, multiple medication trials or with prolonged psychotherapy to which the patient is not responding because the longer the patient’s depressive episode lasts, the more difficult it may be to treat (Bielski and Friedel, 1976; Rush, Hollon, Beck, et al., 1978). For example, patients who have not remitted with one or two well-conducted antidepressant medication trials (with or without psychotherapy) or, for less severe cases, a trial of psychotherapy not exceeding 12 weeks are likely candidates for consultation or referral.

Third, a consultation or referral to a specialist is always an option throughout the patient’s management. It may be called for immediately, for example, if the patient is suicidal, or later. Consultation or referral to a specialist is particularly appropriate in the following instances:

This summary of the methods used by the panel to evaluate treatments considered in this document provides the reader with a better understanding of the scientific basis and limitations of these guidelines, as well as an appreciation of the current state of the depression literature and the methodological and research issues that need further investigation. (See Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming, for more detail.)

The Depression Guideline Panel’s charge was to determine the efficacy of various treatments for major depressive disorder in patients likely to be seen by primary care providers. The ideal evidence on which to base conclusions would be randomized controlled trials of the various therapies conducted in primary care settings with outpatients who have major depressive disorder. A perusal of the literature reveals few such studies.

The panel, therefore, constructed an indirect model, incorporating information from non-primary care settings, and extrapolated this information to the setting of interest. The general strategy was to identify all relevant literature, summarize the results in evidence tables, combine results across each study using meta-analysis, and compare the efficacy of alternative therapies.

The literature was reviewed systematically by establishing a priori criteria for relevant studies, specifying key words (see Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming), reviewing abstracts selected by computer searches, compiling and reviewing the full articles, compiling evidence tables summarizing these articles, and conducting meta-analyses where possible.

Selection of Evidence. The panel considered only published, peerreviewed randomized controlled trials as appropriate evidence to support these guidelines for the treatment of major depressive disorder. This decision was based on the notion that absolute confirmation of the efficacy of a treatment was a prerequisite for any consideration of effectiveness.1 The randomized controlled trial is the clearest scientific method for judging comparative efficacy. The panel made this decision with knowledge of the limitations of randomized controlled trials, particularly considerations of generalizability with respect to patient selection and treatment quality. 1"Efficacy" refers to the performance of the treatment under controlled, research-defined conditions. "Effectiveness" refers to the actual outcomes obtained in routine practice.

Analysis of Treatment Effect. The success of a treatment studied in a randomized controlled trial can be reported in a number of ways. Some may ask, “How many patients randomized to the treatment got better?” This question is answered by an intent-to-treat analysis, which uses the number of patients who got better (regardless of whether they remained in the study) as the numerator and the number randomized to the treatment as the denominator. Others may wonder, “Of those who received at least the minimal amount of treatment thought to be effective, how many got better?” This question is answered by an adequate treatment analysis, which considers only those patients who received a predetermined minimum amount of treatment (typically 3 to 4 weeks for medication and 4 to 6 weeks for psychotherapy in major depressive disorder) as the denominator and counts as the numerator those who responded. Finally, a completer analysis includes only those who received the full treatment package in both the numerator and the denominator.

These distinctions are critical. For example, 100 patients may be randomized to the treatment; 80 may continue the treatment for 3 weeks (the minimum amount of time necessary to achieve a response), and 40 may continue the treatment until its termination. Imagine that a full course of treatment is 95 percent efficacious, that an adequate course of treatment is 75 percent efficacious, and that none of the patients who drop out get better. In this example, the intent-to-treat response rate is (.95) (40/100) or 38 percent, the adequate treatment response rate is (.75) (40) + (.95) (40/80) or 78 percent, and the completer response rate is (.95) (40/40) or 95 percent. Thus, depending on which parameter is chosen, an investigator can claim a success rate anywhere between 38 and 95 percent.

A modified intent-to-treat analysis was used in the treatment section of these guidelines. The denominator for this analysis was the number of patients randomized to the treatment. In most studies, the numerator was the number of patients who stayed in treatment and got better. This modification was made because few studies presented sufficient data to permit calculation of true intent-to-treat numbers, while many provided enough information to permit calculation of the modified percentage. If some patients who left a study got better anyway (which is quite probable), these modified percentages may be lower than those derived from a true intent-to-treat analysis. It is unlikely, however, that this bias would be substantially different among treatments; thus, the between-treatment comparisons should remain valid.

Outcome Measures. As it is the patients who experience the pain and suffering associated with depression, the best way to measure a treatment’s effectiveness is to determine whether the patients are feeling and functioning better.-Most randomized trials of therapies for major depressive disorder use standardized measures of depressive symptoms completed by the clinician (e.g., the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960, 1968], the Clinical Global Impression [CGI; Guy, 1976]) or by the patient (e.g., the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, et al., 1961]) to determine treatment effectiveness. Less often, measures of marital, social, or occupational functioning are used to supplement depression symptom ratings. Ideally, future studies will use a battery of outcome measures that, together, create a complete vision of the patient’s level of well-being and functioning.

For medication studies, the panel chose to use the percentage of patients with a 50 percent reduction in HAM-D score or a CGI response of 1 or 2 (markedly or very much improved) as the primary outcome measure, because these were the most commonly reported categorical outcome measures, thereby rendering the greatest number of studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

For psychotherapy studies, the BDI was by far the most commonly used measure. Analysis showed a correlation coefficient of .84 between the BDI and the HAM-D, demonstrating that the two are well correlated with each other. A meta-analysis of the difference in percent response as determined by HAM-D and BDI in the 18 limbs of the six studies that reported both of these parameters resulted in a distribution with a mean of 2.6 percent, suggesting that the BDI may report a 2.6 percent greater response than does the HAM-D when applied to similar patients. However, there is a 19.6 percent chance that the HAM-D will show a higher response rate than does the BDI; therefore, until further evidence is accrued, it is best to think of the two measures as generally equivalent. Such an assumption does not appear to put psychotherapy at a disadvantage when it is compared to medication trials that used the HAM-D.

Scoring of Outcomes. Treatment outcome in a randomized trial is commonly reported in one of two ways. In categorical scoring, a set of rules is used to place all patients into two or more categories (e.g., “better” versus “not better”), and the percentage of patients in each category is reported. In continuous scoring, a standardized measure of depressive symptoms is administered before and after treatment, and the change in group mean score is reported. Categorical scoring addresses the question that interests most patients: How likely am I to get better if I take this treatment? The results of continuous scoring are of interest to researchers: What is the average amount of improvement a patient can expect by taking this treatment?

The two methods are not mutually exclusive, and it would be best if both were reported in all trials. In this analysis, the panel used categorical data, because they are of greatest interest to patients. Sufficient data were available to provide a reasonable number of studies for meta-analysis.

Preparation of Evidence Tables. To evaluate the literature systematically, each article that met inclusion criteria was read and scored by the author of the review and then abstracted to the appropriate evidence table. (See Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming, for the evidence tables.) For medication studies, three summaries were prepared for each treatment. The first reports the percentage of patients who recovered and contains an entry for every eligible trial that included the treatment as one of its arms. The second reports the difference in response rate between the treatment of interest and placebo. This summary includes an entry for each study that has both an arm containing the treatment of interest and a placebo limb. The third compares the response rate of the treatment of interest to all other established treatments. This listing includes an entry for each study with a limb containing the treatment of interest and a limb containing another established treatment. Thus, a single study may be listed in one, two, or three summaries for a given treatment and may appear in evidence tables for more than one treatment.

A similar approach was used for psychotherapy studies, with tables outlining the percentage of patients who responded to the treatment of interest, the results of treatment compared to the results of another fully representative psychotherapy package or medication, and the effectiveness of therapy versus placebo and versus wait-list.

Methodology and Limitations. The panel used meta-analysis following the confidence profile method (CPM) to calculate summary statistics that describe the likely effects of each treatment considered. (Details can be found in Eddy, Hasselblad, and Schacter, 1990.) Using a hierarchical Bayesian random-effects model, the panel calculated the probability distribution describing the results that would be expected if a hypothetical additional study, similar to the ones included in the analysis, were performed. By taking into account the heterogeneity of study results, this type of analysis depicts the range of results that practitioners can expect should they use the treatment in their own practice settings.

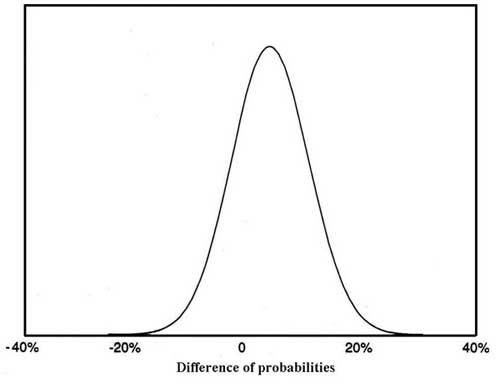

Each meta-analysi~s produces a probability distribution depicting the likelihood that the parameter of interest falls within any particular range of values. For example, the meta-analysis result depicted in Figure 2 indicates the difference in success rate for two alternative therapies. The curve represents the percent difference in success rate between the therapies. It can be said that the mean difference between them is 5 percent (.05), with a standard deviation of 6.6, that 95 percent of the area under the curve (the Bayesian equivalent of a 95 percent confidence interval) lies between -8 and 17.7 percent, or that there is a 22.5 percent chance that the actual difference is less than zero. Since Figure 2 is a probability distribution, it is easy to

Figure 2. Example of a meta-analysis result (mean 5 percent, standard deviation 6.6)

determine the probability that the true difference in the effect of the treatment is greater than, less than, or equal to any selected value. The standard deviation suggests the shape of the distribution; distributions with small standard deviations relative to their mean are tall and narrow, indicating a high degree of certainty regarding the result.

Several factors can compromise the internal validity of the metaanalyses. First, while the random effects model accounts for among-study variations and, therefore, for random bias, it cannot account for any systematic biases that occurred in all of the studies. Second, to be included in the meta-analysis, studies had to include sufficient data to permit calculation of the percent response for each treatment, based on a modified intent-to-treat analysis that used either the HAM-D or the CGI (medication trials) or the BDI (psychotherapy trials). If studies without sufficient data to permit inclusion were fundamentally different from those that were included, summary statistics may be biased. Similarly, a variety of publication biases (particularly the tendency to publish only those studies with positive findings) may result in biased summary statistics.

On the other hand, the hierarchical random effects model is robust. Sensitivity analyses reveal that it would take a huge number of very large studies to change the results in any important way.

Threats to the external validity of the meta-analysis relate primarily to the generalizability of the study populations. While most studies entered a well characterized group of patients with major depressive disorder, others included small, but unspecified, numbers of patients with bipolar disorder or other psychiatric co-morbidities. It is, therefore, difficult to state with certainty the patient populations that the meta-analyses describe. Evidence suggests that patients with different types of depression have different prognoses and react differently to treatment. For example, the placebo response rate for nonpsychotic major depressive disorder is on the order of 25 percent, while the placebo response rate for psychotic depressions is only about 10 percent (Schatzberg and Rothschild, in press). In the absence of knowledge about the exact case mix included in the meta-analysis, caution is necessary to avoid overstating the degree of certainty that is assigned to the results.

Limitations in Comparisons Across Trials. After the meta-analyses have been performed, there is a great temptation to make direct comparisons between summary statistics for medication and psychotherapy trials. Such comparisons should be approached with caution because of the following limitations:

Given these limitations, comparisons of medication and psychotherapy trials should not be given undue importance and should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing.

Generalizability Issues. Although randomized trials provide the best evidence for the efficacy of a treatment in a specific type of patient, their applicability to the community at large may be limited by the trials’ stringent enrollment criteria, unique treatment settings, and unrepresentative clinical procedures. While researchers are working to design methods that address this problem (see Cross Design Synthesis: A New Strategy for Medical Effectiveness Research, US GAO B244808, 1992), these methods were not yet sufficiently developed for use in this project. For these reasons, the panel restricted its analysis to clinical trials. Two caveats must be emphasized, however, one related to patient populations and the other related to treatment quality.

The purpose of these guidelines is to make recommendations regarding the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care settings. Analyses rely on the results of clinical trials that were typically performed in academic psychiatric settings and involved patients without other medical problems. This methodology raises concerns. First, clinical trials require patient consent and participation. Many patients decline a protocol for various reasons (e.g., too severely ill to accept the additional measurement procedures, fear of being placed on a placebo or wait-list, desire for medication, desire for psychotherapy). Thus, patients who enroll in trials may not be representative of the population of interest. Second, clinical trials of medications are often sponsored by pharmaceutical companies seeking Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for their products. To optimize the chances of a good result and to avoid problems with human subject protection committees, these studies typically exclude patients with important medical co-morbidities. Because many patients treated in primary care settings have such co-morbidities, the population of interest is different from the population summarized by the meta-analysis. It is not possible to determine, from the available evidence, how depressed patients with medical co-morbidities will respond to the various therapies. While the few studies done in primary care settings demonstrate response rates similar to those found in psychiatric settings, they are few in number, and they, too, have generally excluded patients with medical co-morbidities.

Randomized controlled trials are often conducted in research settings and always follow a prespecified protocol. Psychotherapy is often specified in a written “manual,” with therapists restricted to particular procedures in research trials. For these reasons, the type of treatment provided as part of a clinical trial may differ substantially from that provided in routine practice. Thus, inferences from research trials to day-to-day practice remain tentative, as protocol-driven treatments may perform better or worse than do their community practice counterparts.

Potential Problems with Meta-Analysis Interpretation. Any time a new method for generating numerical output—in this case, meta-analysis —becomes available, there is potential for misunderstanding and abuse of the numbers. The panel offers some warnings regarding the meta-analysis presented in this Clinical Practice Guideline.

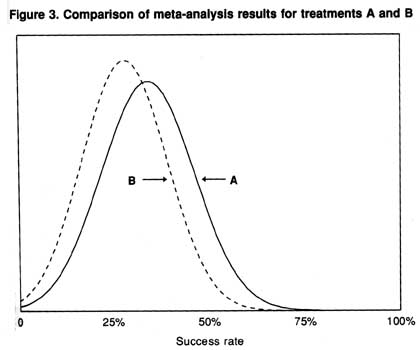

It is important not to attach undue significance to small differences. Figure 3 depicts the results of two meta-analyses, one for treatment A, with a success rate of 34 percent (SD 12), and one for treatment B. with a success rate of 28 percent (SD 11). While comparison of the means reveals that A is 6 percent better than B. there is about a 34 percent chance that B is actually better than A. Therefore, it would be improper to conclude with any certainty that A is superior.

Figure 3. Comparision of meta-analysis results treatments A and B

It is also important not to make improper inferences regarding numbers that are the same. In many cases, the data show that several treatments have similar response rates. These data could lead to the assertion that it is necessary only to use the least expensive agent. This assertion is true if the same patients respond to each treatment. However, there is strong evidence for biologic and psychological heterogeneity among patients with major depressive disorder, which is evident in the differential response of patients to medication (Goodwin and Jamison, 1990; Rush, Cain, Raese, et al., 1991). Thus, for a particular patient, drug A may be ineffective, while drug B may be quite effective; in another patient, the opposite may be true. Furthermore, some research suggests that certain medications may be effective earlier in the longitudinal course of recurrent mood disorders, while others may be better in more longstanding cases (Post, 1992). Similarly, clinical pharmacology studies and clinical experience provide evidence that patients differ in the nature, likelihood, and severity of the side effects that they experience with a medication. One patient may become sedated on a drug, another may develop insomnia, while others have no sleep difficulties. This heterogeneity suggests that more than one agent must be available to ensure adequate treatment of all patients.

| Contents | Previous | Next |