| Contents | Previous | Next |

Pain affects people in different ways. It has both physical and psychological components. It is helpful to understand these components and how they affect not only how the patient responds to pain but how you respond to the patient's pain.

Psychological, emotional or behavioral effects of pain may include any of the following: rigid body position, crying, restlessness or irritability. These responses are due to both fear and anxiety. Think back to a time when you were afraid. Did you have a difficult time concentrating? Were you irritable or short-tempered? Our individual behaviors are influenced by many factors, such as age, sex, culture, religious beliefs, past experience with pain and perceived locus of control. Patients may appear withdrawn, angry, or present a stoic front. Unrelieved pain, as seen in cancer patients or patients with other chronic disorders, may lead to depression and feelings of hopelessness and helplessness.

Religious beliefs may affect how we express or perceive pain. Some people view it as a test which must be passed. Others see pain as a punishment for past sins. Still others believe that suffering is "good for the soul."1 These individuals may behave stoically, or they may deny pain.

Culture also plays a part in how we behave when in pain as well as how we perceive the pain. The meaning of pain and appropriate behavior for one group may not be the same for another group. Certain cultures believe is it unmanly to display any emotion or sign of weakness, while other cultures are more expressive. Health care workers are also affected by their own cultural beliefs and stereotypes. While it is important to be culturally aware, do not expect all patients of a specific culture to respond in the same manner to pain or any other experience. There are differences within as well as between cultures.

Family beliefs and gender stereotypes also play a role in how we respond to pain. If as a child you were taught that boys don't cry, but it's okay for girls to cry, you will carry this with you into adulthood.

Past experience with pain will have different effects on different people, depending on the type of experience. Individuals with no previous experience with pain may be anxious and afraid, due to the fear of the unknown. How long will the pain last? Will it get worse before it gets better? Does it mean I am dying? These questions plague the person in pain. His ability to cope with the anxiety may be affected by fatigue, poor nutrition (due to anorexia, nausea or vomiting) or lack of sleep. Inability to cope with anxiety leads to increased perceptions of pain. Individuals who have had pain, with adequate pain management, are less fearful and more confidant that the pain can be managed. In contrast, individuals who have experienced severe pain that was not adequately relieved become fearful, depressed and experience feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. Frequent experiences with pain cause the individual to anticipate more pain. These individuals develop a sensitivity to pain and exhibit avoidance behaviors.3

The meaning the pain has for an individual will also affect his response. Is it viewed as a challenge, or is it viewed as a punishment? Pain is seen as the enemy, and to some it represents loss and impending death. A person's perceived locus of control will also affect how he responds to pain. Those with an internal locus of control feel that they have control over events in their lives. Those with an external locus of control feel that things keep happening to them that they are powerless to control.3

The environment may effect how pain is perceived. Individuals are affected by hospitalization, strange surroundings, lights, noises, activity, smells, lack of family or friends or too many people in their environment. Nurses can play a major role in reducing environmental aggravators.

Other beliefs that may play a part in pain-related behaviors have to do with our own values and misconceptions. Some individuals are more afraid of becoming addicted to pain medication than they are of the pain itself. This fear may cause them to downplay their pain or to deny their pain. Nurses must deal with their own misconceptions related to addiction and addictive behaviors. As we discussed earlier, the chance of addiction from narcotics when used for pain control is really very small. Patients in hospitals often believe that their pain medication is ordered routinely. "If I was to have pain medication, then the doctor or nurse would have given it to me." We often forget that our patients are not savvy about hospital routines. They don't realize that they need to ask for pain medication. Many times patients are assumed to be pain-free because they fail to request medication. Some individuals think that complaining about pain is "childlike" and that as an adult, they should be able to control it. They take great pains in presenting a stoic front to health care providers and family alike. Many people believe that pain medication should not be taken unless the pain is unbearable. They allow the pain to get out of hand.

Psychological effects of chronic pain are also of major importance to nurses. Chronic pain causes feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. People with chronic pain often feel useless and a burden to their families. These feelings are often due to poor pain control. The pain interferes with activities of daily living, including employment, recreation and interpersonal relationships. These individuals may become withdrawn and depressed. When the chronic pain has no apparent cause, they experience frustration. In addition to the pain, they must deal with the attitudes of others who believe they are lying or lazy. This frustration may manifest itself in anger or manipulative behavior.4

Physical effects of pain are more easily assessed. However, they arenot a reliable guide when treating patients with pain, especially patients with chronic pain. The physical symptoms are due to sympathetic stimulation. Patients in the initial stages of acute pain may manifest such symptoms as elevated blood pressure, tachycardia, rapid respirations, dilated pupils, pallor, diaphoresis, nausea or vomiting. They may also display physical behaviors associated with the pain, such as sensitivity to touch in the affected area, moving away from the source of pain, restlessness or protective posturing.

Other physical signs are related to the cause of the pain, such as injury to an extremity. Patients with fractures, sprains or strains may be unable to walk without pain, or they may limp. Posture may be affected; they may be unable to stand up straight. If the pain is secondary to infection, the individual may have symptoms associated with inflammation, such as redness and swelling.5

When evaluating pain, it is important for nurses to make a thorough assessment. Historically, nurses and other health care providers have assessed pain in a haphazard way. The most obvious problem has been lack of access to valid and reliable instruments. The subjective nature of pain adds to this assessment dilemma. In a review of several nursing textbooks, I found examples of only two assessment tools and descriptions of three others. The instruments available each have strengths and weaknesses. Research needs to be done in this area to provide nurses with reliable tools. Most textbooks agree on the components that need to be included in a pain assessment. They include: location, duration, quantity, quality, aggravating factors, alleviating factors, associated symptoms, behavioral signs, perceptions of pain, meaning of pain, past experience with pain, ability to cope, past medical history, current medications, allergies and recent emotional stress.

Location. Ask the patient to describe or point to the area of the body that hurts. If you have a picture of the body (front and back), that would be helpful. Help the patient to be as specific as possible. Ask guiding questions about the pain. Does it stay in one place? Does it move from area to area? Does it radiate to any other part of the body? Location of pain can be a helpful diagnostic tool.

Duration. Finding out how long the patient has been in pain is also an essential piece of the assessment data. When did it start? How long has it lasted? Sometimes when asked how long they have had the pain, patients will respond with, "for years." You need to ask what is different about the pain at this time that made them seek help.

Quality. Quality is often difficult for the nurse to assess, especially if she does not have a structured instrument to guide the assessment. It is helpful for the nurse to provide cues to help the patient understand how to respond to this question. Is the pain sharp or dull? Is it continuous, intermittent, cramping or burning? Perhaps your patient does not have "pain," but instead describes an intense pressure, pounding or throbbing sensation.

Quantity. When assessing quantity of pain it is helpful to use a chart or scale of some type. This allows the patient to visualize the intensity of the pain. Several of these scales exist. Selection should be based on your patient population. It is important, when using these scales, that everyone use the same one. If your scale is 1-10 and the nurse on the next shift uses a scale from 1-5, the patient will become confused. So, while individuality is often desirable, when dealing with patients in pain, it is more important that all health care providers work as a team. The pain scale being used with a particular patient should be noted in his record and used by all of the team members. Another important consideration, when using pain rating scales, is to teach the patient how to use the scale.

Some of the scales currently in use are the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale, which is commonly used with the pediatric population. It includes six circle faces that vary from smiling, to frowning, to crying. The child is asked to point to the one that best describes how he feels.

Other tools include the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is pictured below:

The patient is asked to place a mark or point to the place on the line where his pain fits. One problem with using this scale is that it is difficult to document.

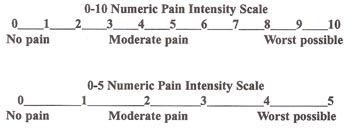

Two other commonly used scales are Numeric Pain Intensity Scales. I have seen them as a scale from 0-5 and a scale from 0-10. Below are two examples of these scales:

These scales are easy to use and provide information for documenting pain, not only during initial assessment but throughout the course of treatment.

Aggravating factors. Asking the patient what things make the pain worse will also help the health care team better understand the patient's pain. Again, you will probably need to ask guiding questions. Ask if the pain is worse when resting or active. Does it hurt to touch the area? Does it hurt to move the area? Does light

or noise make the pain worse? These clues will help the patient understand what it is you want him to explain.

Alleviating/actors. Not only are we interested in what makes the pain worse, we need to know what the patient thinks makes it better. Have you taken any medication for the pain? What type? Has it helped? Does rest alleviate the pain? Does food make the pain better? Does heat or cold help? Again, it may be necessary to provide cues to the patient and ask guiding questions.

Associated symptoms often provide clues to the health care team regarding the etiology of certain specific types of pain. The patient should be asked about vision problems, such as blurred vision or spots. Other associated symptoms include nausea, vomiting, lack of appetite, numbness, weakness or dizziness.

Timing of pain. Another important piece of assessment data is the timing of the pain. Does it occur in the morning or at night? Does it occur at any time? Does it awaken the patient from a sound sleep? Is it worse before or after meals? Does it occur with activity or rest?

Physical symptoms. While it is important to assess physical symptoms, the nurse must remember not to rely on them as the exclusive source of pain assessment data. The physical symptoms to assess include: vital signs, posturing, skin color, diaphoresis, facial expression and behaviors (such as crying or moaning).

Perception and meaning of pain. This area is frequently overlooked by nurses and other health care providers. Ask the patient to describe what the pain has meant in his life. Does it prevent him from working? Does it prevent enjoyment of recreational activities? Has it affected personal relationships?

Past experience with pain and ability to cope. We know that past experience affects the way we respond to pain, so it is helpful for the nurse to understand the patient's previous pain experience. Was the pain acute or chronic? Was it adequately relieved within a reasonable amount of time? Was it self-limiting? Ask your patient about current and previous coping strategies that he may have used to control or cope with pain. Were these successful? Ask the patient if they have been under any emotional stress recently.

Past medical history. It is important to understand what other factors might have precipitated the patient's pain. Is there a history of diabetes, heart disease, renal disease, arthritis, sickle cell anemia? Be sure to investigate this area completely. Also ask the patient about drug and food allergies, as well as a list of all medications being taken (including OTC drugs).

Patient expectations. Remember to end the initial interview by asking the patient what he thinks is the cause of the pain as well as what the patient's expectations for pain relief are. If the patient expects to leave pain-free and he does not, he will be dissatisfied with the care he received.

Pain assessments need to be done at several times. An initial assessment should include all of the information we just discussed. In addition, the nurse should conduct an ongoing pain management assessment. The final assessment should be based on patient outcomes. It is important to carefully evaluate any instrument you use for its appropriateness to the patient population. Factors such as age and reading ability may lead you to select one instrument over another. The data you obtain will only be as good as the instrument you choose. Using an inappropriate instrument will not provide much useful data. All instruments should be based primarily on patient self-reports. It is helpful to use instruments that are short enough to make them practical for the clinical setting. As an emergency room nurse, I prefer that no instruments be longer than one page. If your institution currently has a pain management standard, you should follow its guidelines. In many institutions, this is not the case. Perhaps you could start the ball rolling by instituting a pilot project on your unit.

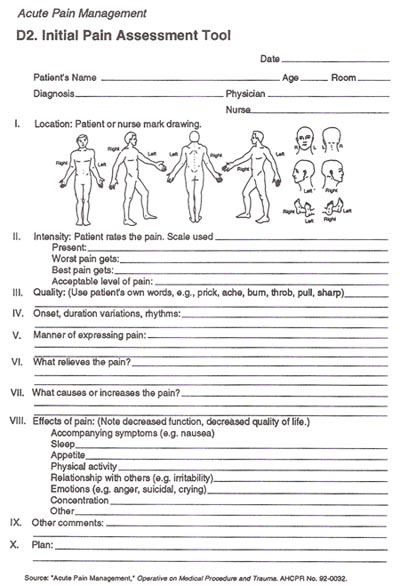

There are several instruments available for use. McCaffery has one that guides the nurse through the intial assessment. It includes pictures of the human body to make it easier for the patient to locate the pain. In addition, there are spaces to fill in: the patient's pain rating, the quality of the pain, the onset of the pain (see form Acute Pain Management, D2. Initial Pain Assessment Tool), and the duration of the pain. You are also guided through associated symptoms, disturbances of activities of daily living and emotional issues. The instrument is only one page in length. This instrument could be adapted for use with both inpatient and outpatient populations.

Other shorter forms exist but offer very little guidance, especially to the novice. One of these is called the PQRST Outline. Its letters stand for various areas the nurse needs to assess. It in no way provides a comprehensive assessment, but it is quick and easy.

P: provocative or palliative factors

Q: quality of the pain

R: region or location of the pain

S: severity of the pain

T: temporal characteristics

Another guide is the acronym PAINS. Again, this is short, but it lacks many of the specifics required of a complete assessment. This format is seen below:

P: place and pattern of experience

A: appearance of patient

I: intensity of pain

N: narcotic and non-narcotic medication

S: space of time

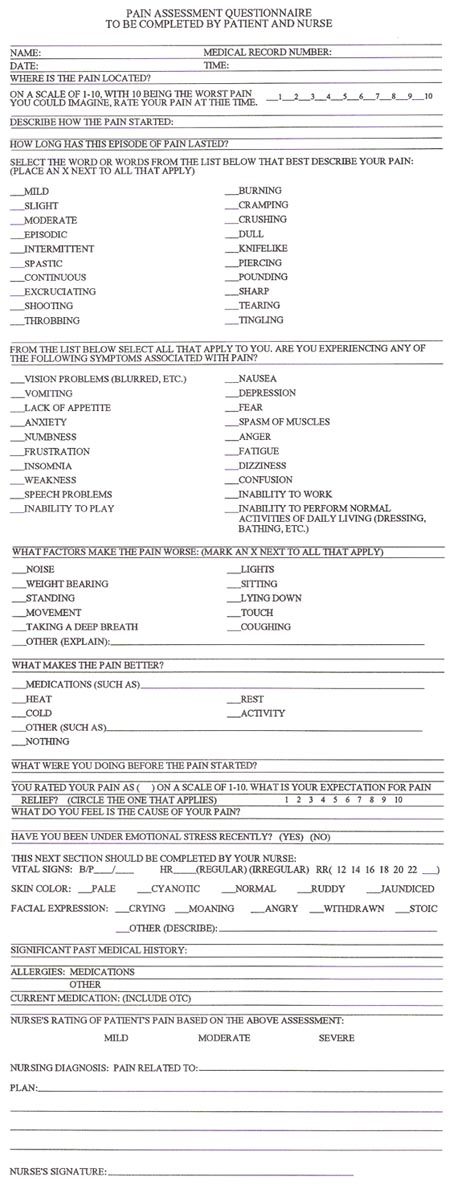

Other guides have certainly been developed. Space does not permit me to include them all. However, what I really want to point out is the need to select an instrument which meets your needs and fits the patient population with whom you work. Since I work in an emergency room, I have developed an instrument for use with the adult patient population in an emergency department. It was developed from the readings of several authors but is primarily derived from the work of Meinhart and McCaffery. It has not been tested for reliability or validity at this time. I offer it only as an example of how to incorporate all of the required data into one short instrument. This instrument is one page, front and back. It was designed to provide structure and consistency between nurses when assessing pain. It has a large self-report section, followed by a section for the nurse to complete. Many of the questions require the patient or nurse to select an answer from several options. It includes a pain rating scale. I have included a copy on the next page for you to critique. Based on the information we have discussed, what areas could be improved? What are the strengths of the instrument? Have I omitted any areas? Could you complete this form in a relatively short period of time? Is it practical?

Assessment of chronic pain has several special components. Chronic pain assessment deals more with the effect the pain has on the patient's perceived quality of life. Does it affect his ability to perform activities of daily living? What impact has the pain had on the individual's life and the life of his family? What is his perception of how other people respond to his pain? Several instruments have been developed. Probably the most famous of these is the McGill Pain Questionnaire. This instrument uses a list of words which describe pain. The patient marks each that apply. This instrument was developed by Melzack in 1975.11 Another instrument is the West Haven Multidimensional Pain Inventory which is used to measure the subjective experience of chronic pain." For those who would like to investigate this area in more depth, another instrument which evaluates the personal response to life with pain can be found in the journal. Research in Nursing and Health (1989).12

Pain management does not end with the administration of a pain medication, and assessment does not end with the initial assessment. The nurse has a responsibility to assess the effectiveness of the pain management interventions and to alter the pain management plan based on this assessment. Is the pain the same, better, or worse? How is the patient responding physically? What are the vital signs? What is the level of sedation? (See chart.) What is the respiratory rate? In the emergency room, these last two areas need to be monitored closely, as we are the ones who often give the first dose of a specific drug. Most patients who have respiratory depression secondary to analgesia have it after the first dose. If the pain medication is not working, the nurse needs to plan the next step for pain management.

When documenting pain management assessment, it is helpful to have a special form. This will provide cues to the nurse in order to prevent omissions. A documentation flow sheet for pain management should include: nursing diagnosis, medication orders, pain-rating scale (to be used before and after each intervention), vital signs, sedation level, evaluation of pain management plan and a place to record revisions. Discharge planning and patient education should also be included.

|

SEDATION LEVEL |

| (0) Sleeping, easily aroused - no action needed |

| (1) Awake and alert - no action needed |

| (2) Occasionally drowsy but easily aroused - no action needed |

| (3) Frequently drowsy, drifts off to sleep while talking - action needed |

| (4) Somnolent, only slight response to stimulation - action needed |

One reason for using an assessment instrument for the management of pain is that nurses tend to overestimate pain relief and underestimate pain severity.13 At times nurses seem more concerned with assessing patients for addiction than with assessing for pain severity. 14 Studies demonstrate that nurses tend to decrease pain medication doses when patients exhibit signs euphoria, regardless of the patient's self-report of pain intensity.15 The use of an assessment instrument to evaluate pain management interventions helps the nurse avoid many of the pitfalls due to personal bias and lack of knowledge regarding pain management. Flow sheets need to be developed for specific nursing areas. I have included an example from McCaffery and Beebe for use in the inpatient setting. See D3. Flow Sheet—Pain.

| D3. Flow Sheet - Pain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Patient______________________________________________________ Date_________________________________________ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| * Pain rating scale used ______________________________________________________________________________________ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Purpose: to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the analgesic(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Analgesic(s) prescribed: ______________________________________________________________________________________ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| * Pain rating: A number of different scales may be used.

Indicate which scale is used and use the same one each time. For example,

0-10 (0=no pain, 10=worst pain). + Possibilities for other columns: bowel function, nausea and vomiting, other pain relief measures. Identify the side effects of greatest concern to patient, family, physician, and nurses. ■ May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Used with permission from McCaffery, M. and Beebe, A. Pain: Clinical Manual for Nursing Practice. (1989). St. Louis: C. V. Mosby. |

Again, since I work in an emergency room, I have designed a pain management flow sheet for use with an emergency department adult patient population. I have included it on the following page to give you an example of the types of information that need to be documented. As with my previous instrument, this one has no reliability or validity testing with which to evaluate it. It includes both pain rating and sedation rating scales. What other items might I have included? Is it too long? Is it practical? How can it be improved? Would it work with your patient population? These are all factors to be considered when selecting an instrument for use with your patient population.

There are several steps involved in the implementation of standards of care for pain management. Initially, assess the current status of pain management at your facility. Assess both patients and staff. Are patients satisfied with the pain management they received? Do nurses routinely document pain assessment, including patient self-reports of pain and the use of a rating scale?

Assess the staffs' knowledge of pain assessment and pain management standards. Research the topic of pain management, and obtain the latest recommendations from the experts. Use these standards as a basis for structuring an education program for the staff. Nurses need information on analgesics and rating scales. They also need information on how to assess for pain, pain relief and sedation. Select and incorporate assessment tools and analgesia flow sheets.

After implementing the standards, it is important to monitor quality improvement. Are patients more satisfied with pain relief measures now than they were during the initial survey? Are nurses assessing pain and pain management according to the established standards? Chart audits and patient surveys are helpful ways to evaluate your quality improvement. On the following pages I have included an example of a patient survey and an audit tool designed for use in an emergency department. See Patient Questionnaire on Pain Management Experience and Quality Assessment Tool. You can incorporate these ideas or develop instruments for your department or institution.

|

PATIENT QUESTIONNAIRE ON PAIN MANAGEMENT EXPERIENCE EXPERIENCE |

| INSTRUCTION: PLEASE DO NOT PUT YOUR NAME ON THIS FORM, WE ASK YOU TO COMPLETE THE QUESTIONNAIRE TO HELP US BETTER SERVE YOU. ALL QUESTIONNAIRES ARE CONFIDENTIAL AND WILL IN NO WAY AFFECT THE CARE YOU RECEIVE NOW OR IN THE FUTURE. |

| WERE YOU ASKED TO RATE YOUR PAIN USING A PAIN SCALE, SUCH

AS 1-10, WITH 10 BEING THE WORST PAIN YOU EVER EXPERIENCED? (Circle one) (YES) (NO) |

| WERE YOU PROMPTLY TREATED FOR YOUR PAIN? (Circle one) (YES) (NO) |

| DID YOU GET RELIEF FROM YOUR PAIN AFTER ONE HOUR? (Circle one) (YES) (NO) |

| DID YOU GET RELIEF FROM YOUR PAIN PRIOR TO DISCHARGE? (Circle one) (YES) (NO) |

| IN ADDITION TO MEDICATIONS, WHAT WAS MOST HELPFUL IN RELIEVING YOUR

PAIN? |

| HOW WOULD YOU RATE YOUR EXPERIENCE? (CIRCLE ONE) POOR FAIR GOOD EXCELLENT |

| HOW WOULD YOU CLASSIFY YOUR PAIN? (CIRCLE ONE) 1. ACUTE (SUDDEN ONSET) 2. CHRONIC (CONTINUOUS) 3. CHRONIC (EPISODIC) |

| DID YOU RECEIVE DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS TO HELP YOU DEAL WITH THE PAIN

WHEN YOU WENT HOME? (Circle one) (YES) (NO) |

|

QUALITY ASSESSMENT TOOL |

|

| MEDICAL RECORD NUMBER: __________ DAY OF THE WEEK PATIENT TREATED: __________ | |

| TIME OF DAY PATIENT ARRIVED IN ED: __________ (USE MILITARY TIME) | |

| ASSESSMENT | |

| INITIAL ASSESSMENT QUESTIONNAIRE COMPLETED BY PATIENT AND NURSE | ___YES ___NO |

| IF NOT INCLUDE RATIONALE FOR OMISSION ___ |

|

| PAIN RATING SCALE (STANDARD 1-10) USED IN CHARTING PRIOR TO TREATMENT | ___YES ___NO |

| PAIN RATING SCALE (STANDARD 1-10) USED IN CHARTING AFTER TREATMENT | ___YES ___NO |

| PAIN CONTROL FLOW SHEET COMPLETED | ___YES ___NO |

| SIDE EFFECTS OF MEDICATIONS DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| SEDATION LEVEL DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| MEDICATION ADMINISTRATION DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENTS DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAN DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| DISCHARGE PLANNING DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| PATIENT EVALUATED WITHIN 1 HOUR AFTER MEDICATION | ___YES ___NO |

| PATIENT EDUCATION RELATED TO PAIN MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTED | ___YES ___NO |

| REVIEWER: DATE: | |

| SCORE: TO SCORE THIS INSTRUMENT GIVE 1 POINT FOR EACH YES ANSWER | |

| TOTAL SCORE ___ / 12 | |

| It is suggested that 10-12 charts be pulled at random each week to assess the quality of pain management and the use of accepted standards and protocols. | |

Answer each of the following questions:

Answers

1. e

2. c

3. c

4. b

5. a

6. e

7. e

8. a

9. c

10. d

11.c

12. c

American Pain Society of Pain Management Nurses

6437 Brooklyn Road, Suite A

Rochelle, IL 61068

(815-562-3983)

American Pain Society

5700 Old Orchard Road, 1st floor

Skokie, IL 60077-1024

(708-966-5595)

International Association for the Study of Pain

909 NE 43rd Street, Room 306

Seattle, WA 98105-6021

(206-547-6409)

AHCPR Publications Clearinghouse

PO Box 8547

Silver Spring, MD 20907

If you have instruments developed for the assessment of pain or pain management, patient education material, quality assurance instruments or research instruments that you are willing to share with others, contact:

Jane Roach

City of Hope

1550 East Duarte Road

Duarte, CA 91010