| Contents | Previous | Next |

Cancer is diagnosed in over 1 million Americans annually. About 8 million Americans now have cancer or a history of cancer; half of these diagnoses were made within the past 5 years. Cancer causes 1 c every 10 deaths worldwide (Stjemsward and Teoh, 1990) and is increasingly prevalent in the United States, where it causes 1 of 5 deaths-about 1,400 per day (American Cancer Society, 1994).

Pain associated with cancer is frequently undertreated in adults (Bonica, 1990) and children (Miser, Dothage, Wesley, et al., 1987). Patients with cancer often have multiple pain problems (Coyle. Adelhardt, Foley, et al., 1990). Cancer pain may be due to (1) tumor progression and related pathology (e.g., nerve damage), (2) operations and other invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, (3) toxicities of chemotherapy and radiation, (4) infection, or (5) muscle aches when patients limit physical activity (Foley, 1979). The incidence of pain in patients with cancer depends on the type and stage of disease. At the time of diagnosis and at intermediate stages. 30 to 45 percent of patients experience moderate to severe pain (Daut and Cleeland, 1982). On average, nearly 75 percent of patients with advanced cancer have pain. Of cancer patients with pain, 40 to 50 percent report it as moderate to severe, and another 25 to 30 percent describe it as very severe (Bonica, 1990).

In approximately 90 percent of patients, cancer pain can be controlled through relatively simple means (Goisis, Gorini, Ratti, et al., 1989; Schug, Zech, and Dorr, 1990; Teoh and Stjemsward, 1992;Ventafridda, Caraceni, and Gamba, 1990), yet a consensus statement from the National Cancer Institute Workshop on Cancer Pain indicated that the "undertreatment of pain and other symptoms of cancer is a serious and neglected public health problem” (National Cancer Institute, 1990). The Workshop concluded that"... every patient with cancer should have the expectation of pain control as an integral aspect of his/her care throughout the course of the disease" (National Cancer Institute, 1990).

Because cancer pain control is a problem of international scope, the World Health Organization (WHO) has urged that every nation give high priority to establishing a cancer pain relief policy (Stjemsward and Teoh, 1990). In the United States, many organizations have worked toward this goal (Ad Hoc Committee on Cancer Pain of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 1992; American Pain Society, 1986; Health and Public Policy Committee, American College of Physicians, 1983; McGivney and Crooks, 1984; Spross, McGuire, and Schmitt, 1990a, 1990b, 1990c; Weissman, Burchman, Dinndorf, et al., 1988).

Pain control merits high priority for two reasons. First, unrelieved pain causes unnecessary suffering. Because pain diminishes activity, appetite, and sleep, it can further weaken already debilitated patients. The psychological effect of cancer pain can be devastating. Patients with cancer often lose hope when pain emerges, believing that pain heralds the inexorable progress of a feared, destructive, and fatal disease. Chronic unrelieved pain can lead patients to reject active treatment programs, and when their pain is severe or they are depressed, to consider or commit suicide. Besides mitigating suffering, pain control is important because, even when the underlying disease process is stable, uncontrolled pain prevents patients from working productively, enjoying recreation, or taking pleasure in their usual role in the family and society (Moinpour and Chapman, 1991). Pain control therefore merits a high priority not only for those with advanced disease, but also for the patient whose condition is stable and whose life expectancy is long.

One of the worst aspects of cancer pain is that it's a constant reminder of the disease and of death. Many fear the pain will become unbearable before death, and those of us involved in support networks have seen these fears proven true.

Pain seems greater when dealing with it alone and an increasing number of us are finding comfort in support groups, where we also . deal with issues of personal control, communication with doctors and nurses, effective adjunctive therapies, and other topics.

My dream is for a medication that can relieve my pain while leaving me alert and with no side effects.

— Jeanne Stover, Panel Member 1991-1992

Cancer pain may resolve with the patient's cure or continue indefinitely as a complication of otherwise curative therapy. Although cancer pain is often thought of as a crisis that emerges in advanced stages of disease, it may occur for many reasons and cause suffering, loss of control, and impaired quality of life throughout the patient's course of care, even for the patient whose condition is stable and whose life expectancy is long.

Suffering denotes an extended sense of threat to self-image and life, a perceived lack of options for coping with symptoms or problems caused by cancer, a sense of personal loss, and a lack of a basis for hope. "Suffering can include physical pain but is by no means limited to it.... Most generally, suffering can be defined as the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person.... The suffering of patients with terminal cancer can often be relieved by demonstrating that their pain truly can be controlled" (Cassel, 1982).

Pain can exacerbate individual suffering by worsening helplessness, anxiety, and depression. Shock and disbelief, followed by symptoms of anxiety and depression (irritability and disruption of appetite and sleep, inability to concentrate or carry out usual activities) are common when people first learn they have cancer or discover that treatment has failed or disease has recurred (Massie and Holland, 1990). These symptoms usually resolve within a few weeks with support from family and caregivers, although medication to promote sleep and reduce anxiety may be necessary in crisis periods. "The relief of suffering and the cure of disease must be seen as twin obligations of a medical profession that is truly dedicated to the care of the sick" (Cassel, 1982).

The obligation to alleviate suffering is an essential component of the clinician's broader ethical duties to benefit and not harm; it dictates that health professionals maintain clinical expertise and knowledge in the management of pain, even when present educational programs do not provide this.

— Cain and Hammes, in press; Hammes and Cain, in press

Personal control refers to an individual's ability to shape immediate and long-range circumstances through one's own actions (Wallston, Wallston, Smith, et al., 1987), including:

Personal control is undermined when cancer is diagnosed and is further reduced by ongoing pain, invasive or undignified procedures, treatment toxicities, hospitalization, and surgery. When pain reduces patients' options to exercise control, it diminishes psychological well-being and makes them feel helpless and vulnerable. Therefore, clinicians should support active patient involvement in effective and practical methods to manage pain.

The quality of life of cancer patients with pain is significantly worse than that of cancer patients without pain (Ferrell, Rhiner, Cohen, et al., 1991). Table 1 depicts the effect of pain in four quality-of-life domains — physical, psychological, spiritual, and social.

Family and loved ones of cancer patients share the suffering, loss of control, and impaired quality of life and also experience psychological and social stresses. Family caregivers need sleep and respite from the burdens of care giving and may have socioeconomic needs and fears related to the costs of providing care.

Even in the absence of psychological, emotional, and physical stressors, the family may feel unprepared to deal with the patient's many needs. They often have to assess pain, make decisions about the amount and type of medication, and determine when the dose of medication is to be given. Sophisticated pain management strategies may require them to manage complex medication regimens involving parenteral or epidural infusions in the home.

Some family caregivers may hesitate to give adequate doses of pain medicines out of fear that the patient will become addicted or tolerant or develop respiratory depression (Ferrell, Cohen, Rhiner, et al., 1991). Clinicians should reassure patients and families that most pain can be relieved safely and effectively. Family caregivers may feel unprepared to deal with a patient's need for pain relief or may deny that the patient is in pain to avoid facing the possibility that the disease is progressing. These situations require ongoing discussions among patients, family caregivers, and experienced health care providers about pain management goals.

| Table 1. Effect of cancer pain on quality of life | |

| Physical | |

| Decreased functional capability. | |

| Diminished strength, endurance. | |

| Nausea, poor appetite. | |

| Poor or interrupted sleep. | |

| Psychological | |

| Diminished leisure, enjoyment. | |

| Increased anxiety, fear. | |

| Depression, personal distress. | |

| Difficulty concentrating. | |

| Somatic preoccupation. | |

| Loss of control. | |

| Social | |

| Diminished social relationships. | |

| Decreased sexual function, affection. | |

| Altered appearance. | |

| Increased caregiver burden. | |

| Spiritual | |

| Increased suffering. | |

| Altered meaning. | |

| Reevaluation of religious beliefs. | |

| Source: Ferrell, Rhiner, Cohen, et al., 1991. Used with permission. | |

The anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology of pain and analgesia have been studied extensively. A major advance has been the finding that neural pathways that arise in the brain stem descend to the spinal cord and modulate activity in spinal nociceptive pathways (Fields and Basbaum, 1978). These descending pathways, as well as related pain pathways within and above the spinal cord, respond to opioids and other analgesic drugs as well as physiologic and experimental stimuli, including stress (Mayer and Liebeskind, 1974), to produce analgesia. It has been speculated that the activation of this descending control system by the action of endogenous opioids such as ß-endorphin and enkephalins may account for the phenomenon of placebo analgesia and the apparent analgesic effect of acupuncture in some clinical circumstances.

Pain may be defined as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage" (International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy, 1979). Although the mechanisms of pain and pain pathways are becoming better understood, it should be emphasized that an individual's perception of pain and appreciation of its meaning are complex phenomena that involve psychological and emotional processes in addition to activation of nociceptive pathways (McGrath, 1990a). Pain intensity is not proportional to the type or extent of tissue damage but may be influenced at many sites within the nervous system. The perception of pain depends on the complex interactions between nociceptive and non-nociceptive impulses in ascending pathways, in relation to the activation of descending pain-inhibitory systems. This framework provides the basis for a comprehensive, multimodal approach to the assessment and treatment of patients with pain and fits with the clinical observation that there is no single approach to effective pain management. Instead, individualized pain management should take into account the stage of disease, concurrent medical conditions, characteristics of pain, and psychological and cultural characteristics of the patient. It also requires ongoing reassessment of the pain and treatment effectiveness.

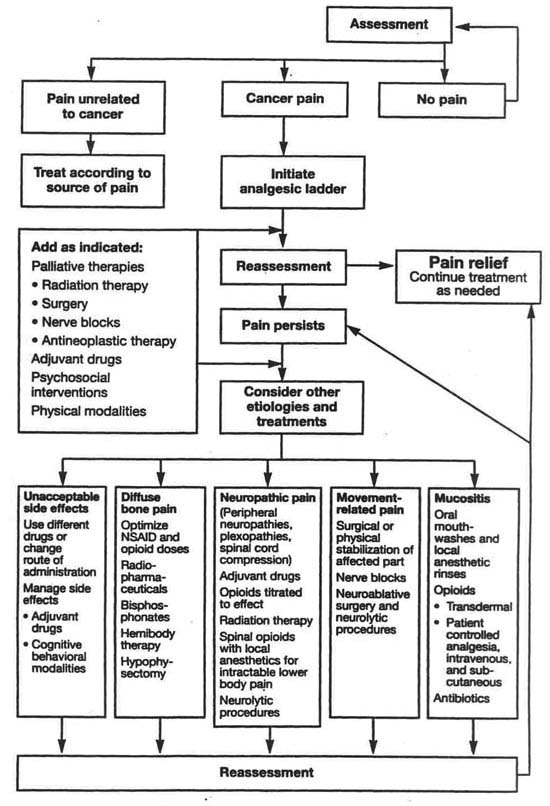

Figure 1 is a flowchart depicting cancer pain management from the initial assessment of pain and its cause to the various treatment modalities, including the WHO analgesic ladder and numerous other drug and non-drug modalities (World Health Organization, 1990). The best choice of modality often changes as the patient's condition and the characteristics of the pain change. It is important that the effectiveness of analgesic modalities used separately or in combination be carefully assessed. The flowchart indicates the complexity of both the sources of pain and the types of modalities available for managing it. This guideline elaborates on the modalities, making recommendations about their appropriate use.

| Figure 1. Flowchart: Continuing pain management in patients with cancer |

|

|

| Figure 2. The WHO three-step analgesic ladder |

|

|

| Source: World Health Organization, 1990. Used with permission |

The WHO ladder (Figure 2) portrays a progression in the doses and types of analgesic drugs for effective pain management. When this noninvasive approach is ineffective, alternative modalities include other routes of drug administration, nerve blocks, and ablative neurosurgery (Figure 3). As Figure 3 indicates, patients receiving treatments of varying degrees of invasiveness may also benefit from other modalities; the number of patients receiving these modalities either separately or in combination has not been well documented. The estimates presented in Figure 3 reflect various clinical populations and may not represent all settings and populations; furthermore, they do not necessarily reflect what is optimal, but only a range of current opinions. There is a need for research to determine the effectiveness of many of these modalities used alone or in combination for different patient populations in various settings.

| Figure 3. Pain Management strategies: a hierarchy |

|

|

Pain management is often needlessly suboptimal (Table 2). Health care professionals are seldom trained in pain management, may not realize the importance of pain management or recognize that a patient is in pain, and may fear prescribing opioid medications.

Like some clinicians, patients and families may shun the use of opioids and, because of their fears of addiction an4 worries about tolerance, may not complain about pain or about poor pain relief. Therefore, the panel recommends that clinicians include patient and family education about pain and its management in the treatment plan.

Another barrier is that pain management has not traditionally been a priority of the health care system. Pain treatment may not be reimbursed or readily accessible, and institutions may be more concerned about a patient's possible opioid addiction or the diversion of controlled substances than about optimizing pain relief. Clinicians should reassure patients who. are reluctant to report pain and who fear addiction and unmanageable side effects that there are many ways to relieve pain safely and effectively. Talking with clinicians knowledgeable about pain management and reading the consumer versions of this guideline (Jacox, Can-, Payne, et al., 1994, in press) should help patients and their families to overcome fears and concerns that hinder effective pain relief.

Problems related to the health care system and suggestions for resolving these are addressed extensively elsewhere (Angarola and Wray, 1989; Cain and Hammes, in press; Cleeland, Cleeland, Dar et al., 1986; Cleeland, 1987; Ferrell and Griffith, in press; Hammes and Cain, in press; Hill, 1993; Joranson, in press; Kolassa, in press; Shapiro, in press, a, b). Two of the problems—restrictive regulation of controlled substances and reimbursement policies—are discussed briefly here.

The Federal government attempts to ensure the availability of opioid analgesics for legitimate medical and scientific purposes while controlling the abuse and illegal diversion of such substances (Shapiro, in press, a). The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is one of the principal Federal laws that affects the use and availability of controlled substances, including opioid analgesics. The CSA provides for the registration of all'handlers of controlled substances, as well as for the labeling, order forms, recordkeeping, and reporting of substances or their use. These activities enable enforcement agencies to identify manufacturers* distributors, clinicians, and pharmacists who divert controlled substances for illicit uses. The CSA also includes provisions that explicitly aim to avoid interference with the availability of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for legitimate purposes. The CSA does not restrict a clinician's medical decision about which drug to prescribe, in what amounts, or for what duration, although it does prohibit physicians from prescribing opioids to maintain narcotic addiction unless the physician is separately registered to treat addiction. "Addict" is defined in the CSA as one who habitually uses an opioid drug so as to endanger public health or safety or one who has lost control over opioid use (Controlled Substances Act, 21 U.S.C., sec. 802). This definition rarely applies to a patient being treated with opioids for cancer pain (Kanner and Foley, 1981). Furthermore, Federal controlled substances regulations clarify that the Federal law is not intended to impose limitations on a physician's ability to prescribe opioid analgesics to persons with intractable pain in situations where no relief or cure is possible or none has been found after reasonable efforts (21 CFR 1306.07(c)).

| Table 2. Barriers to cancer pain management | ||

| Problems related to health care professionals | ||

| Inadequate knowledge of pain management.1 | ||

| Poor assessment of pain.2 | ||

| Concern about regulation of controlled substances.3 | ||

| Fear of patient addiction.4 | ||

| Concern about side effects of analgesics.5 | ||

| Concern about patients becoming tolerant to analgesics.6 | ||

| Problems related to patients | ||

| Reluctance to report pain.7 | ||

| Concern about distracting physicians from treatment of underlying disease. | ||

| Fear that pain means disease is worse. | ||

| Concern about not being a "good" patient | ||

| Reluctance to take pain.8 | ||

| Fear of addiction or of being thought of as an addict. | ||

| Worries about unmanageable side effects. | ||

| Concern about becoming tolerant to pain medications. | ||

| Problems related to the health care system | ||

| Low priority given to cancer pain treatment.9 | ||

| Inadequate reimbursement.10 | ||

| The most appropriate treatment may not be reimbursed or may be too costly for patients and families. | ||

| Restrictive regulation of controlled substances.11 | ||

| Problems of availability of treatment or access to it.12 | ||

|

1 Bontca, 1985; Cleeland, deeland. Oar, et al.. 1986; Ferrell, Cronin Nash, and Warfield, 1992;

Von Roenn, Cleeland, Gonin. et al., 1993. 2 Grossman, Sheidler, Swedeen, et al.. 1992; Von Roenn, Cleeland, Gonin, Hatfield. et al.,1993. 3Joranson, Cleeland, Weissman, et al., 1992; Shapiro, in press, a, b; Von Roenn, Cleeland, Gonin, et al., 1993: Weissman, Joranson, and Hopwood. 1991. 4 Bonica, 1985; Ferrell, Cronin Nash, and Warfield, 1992; Marks and Sachar, 1973. 5 Cleeland, Cleeland, Dar. et al, 1986: Von Roenn, Cleeland, Gonin, et al., 1993. 6 Cleeland, Cleeland, Dar, et al, 1986: Shapiro. in press, a, b. 7 Dar. Beach, Barden. et al., 1992; Levin, Cleeland. and Dar, 1985; Von Roenn, Cleeland. Gonlin et al., 1993; Ward, Golberg, Miller-McCauley. et al.. 1993. 8 Cleeland, 1989; Dar, Beach, Barden, et al., 1992; Modes, 1989; Joranson, in press; Levin, Cleeland, and Dar, 1985; Rimer, Levy, Keintz. et al., 1987; Von Roenn, Cleeland, Gonin, et al.. 1993; Ward, Goldberg, Milter-McCauley, et al., 1993. 9 Bonica. 1985; Max. 1990. 10 Ferrell and Griffith, in press; Joranson, in press. 11 Fotey, 1985a: Joranson, Cleeland, Weissman, et al., 1992: Shapiro, in press, a. b; Weissman, Joranson, and Hopwood, 1991 12 Foley, 1985a. |

||

State laws vary greatly, and many restrict or regulate the prescribing of opioids in the treatment of pain in ways that Federal law does not For example, many State drug diversion laws contain ill-defined terms that in effect restrict opioid prescribing (Joranson, 1990). Other State laws also regulate pain treatment by restricting medication prescriptions to a specific number of dosage units or to a 1-month supply, or by monitoring the prescription of controlled substances through multiple-copy prescription programs. WHO has observed that although multiple-copy prescription programs are intended to reduce careless prescribing, "Health care workers may be reluctant to prescribe, stock or dispense opioids as they feel that there is a possibility of their professional licenses being suspended or revoked by the governing authority in cases where large quantities of opioids are provided to an individual, even though the medical need for such drugs can be proved" (World Health Organization, 1990). In States with formal cancer pain initiatives, health professionals have worked with State agencies to identify and remove legal impediments to the use of controlled substances for cancer pain (Dahl, Joranson, Engber, et al., 1988).

A 1990 revision of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act addresses the legitimate use of controlled substances by recognizing that the prescribing, administering, and dispensing of opioid analgesics for intractable pain is part of professional medical treatment. It states that if terms such as addict, habitual user, and drug-dependent person are used in States' statutes, definitions of these terms should clearly indicate that they do not apply to patients receiving controlled substances pursuant to a practitioner's order (Uniform Controlled Substances Act, 1990). Each State legislature has received the revision from the Uniform Law Commissioners.

The panel recommends that laws and regulatory policies aimed at diversion control not hamper the appropriate use of opioid analgesics for cancer pain. Clinicians are responsible for knowing how controlled substances are regulated in their States. Such information can be obtained from State medical, nursing, and pharmacy licensing boards (see Angarola, 1990; Joranson, 1990; Shapiro, in press, a, for additional information on the regulation of analgesic drugs).

Determining the overall cost of pain management is difficult because it generally is not separated from other treatment costs, but rather is included as part of the patient’s stay in the hospital or an outpatient visit. Components of pain management costs and a comparison of analgesic drug costs are discussed by Ferrell and Griffith (in press) and Kolassa (in press).

Access to professional services, prescription drugs, and medical equipment is usually necessary for effective pain care (Joranson, in press). Reimbursement or lack of it influences the way in which pain is treated, where it is treated, and the supportive care that is available (Yasco and Verfurth, 1992). Reimbursement policies of third-party payers for pain management differ substantially, and many people with cancer are uninsured or underinsured. According to one report (American Cancer Society, 1989), low-income people experience greater pain and suffering from cancer than do other Americans, and a disproportionate share of people with little or no insurance are minorities. For those who are insured, reimbursement policies may favor the use of more expensive pain management modalities over less expensive ones. Medicare, for example, does not reimburse for outpatient oral analgesics but will reimburse for pain management in an inpatient facility. Thus, “a person may well have reimbursement for the $4,000.00 cost of patient controlled analgesia (PCA) morphine but will have no coverage for $100.00 of oral morphine solution” (Ferrell and Griffith, in press). Joranson (in press) has reported on the variation in the policies of private payers and health maintenance organizations, in which policies are often unclear about or offer minimal coverage for pain management Reimbursement policies on pain management should be studied to enable further understanding of those that promote the most cost effective pain management.

Clinicians should consider a patient's ability to pay for treatment. The costs of medication and other treatments may overburden a patient with limited financial resources and result in compromises between adherence to the prescribed regimen and other financial responsibilities (Brand, Smith, and Grand, 1977). Costs of analgesic drugs, for example, including many that are equally effective for pain management, vary dramatically (Kolassa, in press). For example, an analysis of the costs of NSAIDs included in the drug tables of this guideline showed that the retail price of NSAIDs (excluding aceta-minophen and aspirin) in 1992 ranged from $10.50 to $127.80 for a 30-day supply (Kolassa, in press). Although the primary concern of the clinician is to manage pain effectively, the ability to do this may be influenced by the patient's economic status. Therefore, clinicians should collaborate with patients and families, taking cost of drugs and technologies into account when selecting pain management strategies.

This guideline was developed by an interdisciplinary, expert panel, commissioned by AHCPR, that comprises practitioners in nursing, medicine, pharmacy, psychology, and physical therapy; health care consumers; and an ethicist.

The panel used four processes to develop the guidelines. First, it undertook an extensive and interdisciplinary clinical review of current needs, therapeutic practices and principles, and emerging technologies for cancer pain control. This process included a review of all pertinent guidelines and standards, the solicitation of information and opinions from external consultants, and an open forum (announced in the Federal Register and held in Washington, DC, on September 5,1991) to receive the broadest possible input from concerned parties.

Second, the panel performed a comprehensive scientific review of the field to define the existing knowledge base and evaluate critically the assumptions and common wisdom in the field. Although the primary focus of the review was on cancer pain, the panel also reviewed the pain literature on HIV positive/AIDS. When there were few studies available that tested the use of interventions with various populations of cancer patients, studies conducted on other clinical populations were used as supplementary scientific evidence. The panel examined studies on patients of all ages. It performed a best-evidence synthesis of the scientific evidence, including a meta-analysis when sufficient numbers of experimental studies were found in the literature. Nineteen data bases were searched, and approximately 9,600 citations were screened. Six hundred twenty-five research studies were critiqued for scientific merit, and 550 were included in tables of evidence for the various interventions.

Attachment A gives ratings of strength of the scientific evidence for interventions, along with the types and ratings for evidence of the specific interventions included in the guidelines. Briefly, the strength and consistency of evidence for recommendations describes the evidence and notes whether it is generally consistent or inconsistent. Strength of evidence ranges from A (strongest) to D (little or no systematic empirical evidence).

When the strength of evidence is A or B, the panel's recommendations are based primarily on the evidence. When the strength of recommendation is C or D, the panel used the available empirical evidence but based their recommendations primarily on expert judgment. When the recommendation is a statement of panel opinion regarding desirable practice and there is evidence that the practice is not commonly being followed, the term "panel consensus" is used.

Third, guideline drafts were developed by members of the panel, consultants, and panel staff. In all, 17 drafts were written.

Fourth, the panel initiated peer review of two drafts of the guideline and field tested a draft with intended users in clinical sites. Comments were reviewed and incorporated into the final guideline. The patient brochure was developed by panel members and field tested with 69 patients and six clinicians.

Four hundred sixty-eight consultants, peer reviewers, and site testers reviewed and contributed to the development of the guideline. The entire process was anchored by the panel, which met six times over a period of 2 years.

Users of this guideline can easily refer to sections of immediate interest. It begins with a discussion of pain assessment and then presents methods of pain control. These methods appear in separate sections dealing with the pharmacologic management of pain, the use of psychosocial and physical modalities, and the use of anesthetic and surgical interventions and radiation therapy. One chapter discusses procedure-related pain in adults and children. Another addresses pain in special populations, including infants and children, the elderly, known or suspected substance abusers, minorities, HIV positive/AIDS patients, and people with psychiatric problems. The final section discusses institutional responsibility for effective pain management. Attachment A contains tables of scientific evidence for the interventions. Attachment B contains pain assessment instruments for adults and children. Attachment C includes sample relaxation exercises. A glossary, as well as lists of consultants, peer reviewers, and site testers of-the guideline are also provided. To derive maximal benefit, clinicians should read the entire guideline.