| Contents | Previous | Next |

It was spring of 1996 when Beth Bye says she returned from the dead. The Wisconsin woman hadn’t actually died, but with her body ravaged in the late stages of AIDS infection, she had run out of options, and death was, indeed, near. AIDS-related dementia and blindness had crept in—signs that her doctor told her meant time was short. She made funeral arrangements and considered moving to a hospice for her remaining days.

Then, as if to say “not so fast,” medical science handed her another option. New drugs called protease inhibitors, first approved in 1995, were about to revolutionize the treatment of patients infected with the AIDS virus. These drugs usually are taken with two other drugs called reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The combined drug “cocktail” has helped change AIDS in the last three years from being an automatic death sentence to what is now often a chronic, but manageable, disease.

Within two months of beginning the triple cocktail treatment, also known as highly active Antiretroviral therapy (HAART), Bye’s viral load—a measure of new AIDS virus produced in the body—dropped to undetectable levels. Her red and white blood cell counts normalized, an important sign that the immune system was starting to work again. Suddenly she could do simple things she had long given up, such as walk the dog for 2 miles. Bye, now 40, was even able to return to her teaching job and currently works 30 hours a week.

“My recovery was like being on death row and getting that last minute pardon from the governor,” she says.

This so-called “Lazarus Effect,” named for the biblical figure who was raised from the dead, has occurred with many AIDS patients who take the triple therapy. “It returns many who were debilitated and dying to relatively healthy and productive life,” says Richard Klein, HIV/AIDS coordinator for the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Special Health Issues.

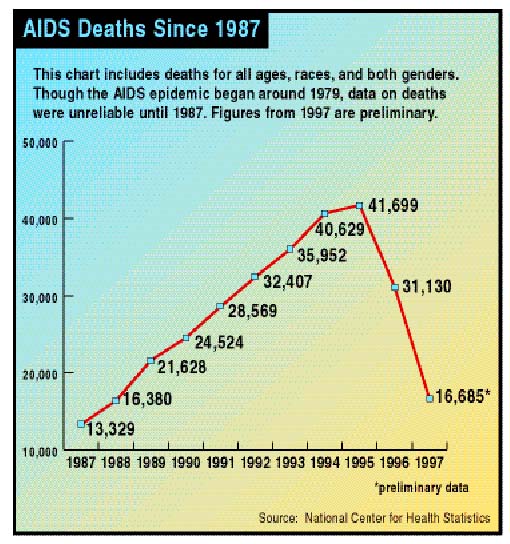

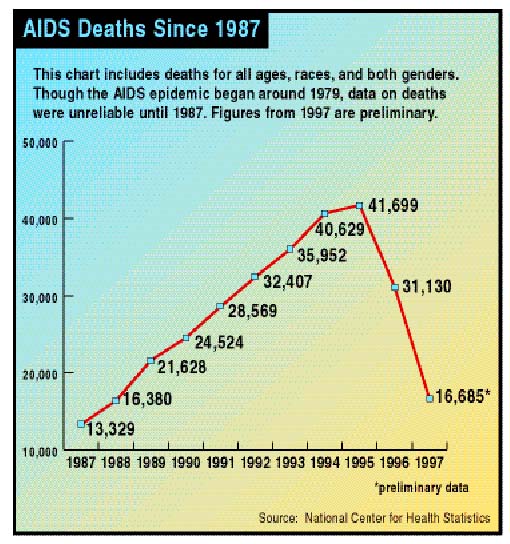

Many health experts, in fact, credit the powerful HAART therapy with helping the domestic AIDS death rate to drop by 47 percent in 1997, the last year for which figures are available. Other factors have contributed as well, says Anthony Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “It is also likely that increased access to care, our growing expertise and experience in caring for HIV-infected people, and the decrease in new HIV infections in the late 1980s due to prevention efforts are partly responsible for the reduction in HIV-related deaths we are seeing today.”

In 1997, for the first time since 1990, AIDS fell out of the top 10 causes of death in the United States, dropping from 8th to 14th place, according to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By 1998, about 16,000 people were still alive who would have died the previous year if AIDS mortality had continued at its former rate. Still, about 40,000 new infections occur yearly.

So far, the combination HAART treatment is the closest thing medical science has to an effective therapy. The key to its success in some patients lies in the drug combination’s ability to disrupt HIV at different stages in its replication. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors, which usually make up two drugs in the HAART regimen, restrain an enzyme crucial to an early stage of HIV duplication. Protease inhibitors hold back another enzyme that functions near the end of the HIV replication process. The combination can be prescribed to those newly infected with the virus, as well as AIDS patients.

FDA approved the first drug specifically to combat HIV and AIDS in 1987. Commonly known as AZT (zidovudine), it is in the family of reverse transcriptase inhibitors called nucleoside analogs. Others in this class include ddi (didanosine), ddc (zalcitabine), D4T (stavudine), 3TC (lamivudine), and most recently Ziagen (abacavir). In 1997, FDA approved Combivir, a mixture of AZT and 3TC that allows patients to reduce the number of pills needed, which can be upwards of 20 a day for certain drug combinations.

Viramune (nevirapine), the first reverse transcriptase inhibitor in a class called non-nucleoside analogs, was approved in 1996. The following year, FDA approved a related drug, Rescriptor (delavirdine). In 1998, a third drug in this class, Sustiva (efavirenz) was approved.

Protease inhibitors, the last part of the triple cocktail, have only been on the market about three years. FDA approved the first one, Invirase (saquinavir), in late 1995.

Others approved since include Norvir (ritonavir), Crixivan (indinavir), Viracept (nelfinavir), and Crixivan (amprenivir). Viracept was the first of its class to be labeled for use in children and adults. Norvir and Crixivan are now approved for children as well. FDA also has approved Fortovase, a new formulation of saquinavir that comes in a soft gelatin capsule that allows more drug to be absorbed into the body than the earlier version.

Though the use of protease inhibitors with other AIDS drugs has had a drastic impact on the health of HIV and AIDS patients, there are drawbacks. For example, the HAART treatment is not an AIDS cure, says FDA’s Klein. Though HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, may not be detectable in the blood following successful HAART treatment, experts generally feel that the virus is still present, lurking in hiding spots such as the lymph nodes, the brain, testes, and the retina.

“The improved sense of well-being, and the belief that lower viral load means they will not transmit the virus, has translated, in some communities, to a lapse in certain prevention practices,” Klein says. He adds that this is dangerous because infected people, even with diminished viral counts, can spread the virus.

Another concern is that the combination therapy, besides being very expensive, requires a much more complicated treatment regimen. “Patients need to stay aware of and adhere to their dosing schedule,” says Klein. “If not taken on a strict regimen, protease inhibitors can result in the emergence of HIV strains that are resistant to treatment.” Numerous studies also have shown that viral load can rapidly “rebound” to high levels if patients discontinue part or all of the triple therapy regimen.

AIDS treatments may interact with many commonly prescribed drugs. For example, Pfizer Inc. plans to label its impotence drug Viagra to warn of possible interactions with certain protease inhibitors, which appear to raise levels of Viagra in the blood.

AIDS drugs also may prompt onset of diabetes or a worsening of existing diabetes and hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), along with increased bleeding in people with hemophilia types A or B.

Some patients on triple therapy have experienced a type of weight redistribution where face and limbs become thin while breasts, stomach or neck enlarges. Some have nicknamed the appearance of fat deposits at the back of the shoulders “buffalo hump.” Fat deposits in the midsection are sometimes called “Crix belly,” after the drug Crixivan, “although it has been seen in people taking all approved protease inhibitors,” says Klein.

Research is currently under way to determine if protease inhibitors cause a permanent change in fat metabolism. “There is considerable concern over the long-term effects for patients,” says Klein, including the possibility that the cholesterol increases in some patients who experience fat redistribution could increase the risk for cardiovascular complications such as strokes or heart attacks. FDA has asked each of the makers of protease inhibitors to study these abnormalities.

Because AIDS patients have suppressed immune systems, they can fall prey to certain illnesses that people with healthy immune responses don’t get, or get only very rarely. One common such illness is Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), which can be life-threatening. Treatments to prevent PCP are NebuPent (aerosolized pentamidine), a fine mist inhaler, and drugs such as Bactrim and Septra that contain both trimethoprim and sulfa. Mepron (atovaquone) is approved for treating mild-to-moderate PCP in pregnant women and patients who cannot tolerate standard treatment. Neutrexin (trimexetrate glucoronate) also is approved for pregnant women and for moderate-to-severe PCP when given with Leucovorin (folinic acid).

Cytomegalovirus retinitis is a potentially severe AIDS-related eye infection that can lead to blindness. Approved treatments include ganciclovir, marketed as Cytovene in oral dosage and as Vitrosert as an implant, Foxcavir (foscarnet), and Vistide (cidovir).

For mycobacterium avium, an infection that before AIDS was almost always confined to patients with severe chronic lung diseases such as emphysema, FDA has approved Biaxin (clarithromycin), Mycobutin (rifabutin), and Zithromax (azithromycin).

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a type of AIDS-related cancer that causes characteristic purple or pink skin tumors that are flat or slightly raised. Intron A (human interferon-alpha), doxorubicin liposome injection, or daunorubicin citrate liposome injection can be used to treat KS. Panretin, a topical gel, also is approved for treating certain types of KS lesions.

AIDS wasting syndrome involves major weight loss, chronic diarrhea or weakness, and constant or intermittent fever for at least 30 days. Approved treatments include Marinol (dronabinol), Megace (megestrol), and Serostim (somatropin rDNA for injection).

In 1998 recommendations, the Public Health Service Task Force stated that the decision to take anti-HIV drugs during pregnancy should be made by the pregnant woman after her healthcare provider has explained benefits and risks. There are some compelling reasons to take the drugs. For example, an HIV-positive pregnant woman who takes AZT after the first trimester decreases the chance of the baby being born with HIV. Studies show that AZT taken according to a strict regimen decreases by nearly 66 percent the odds of infecting the newborn.

The task force says women should consider delaying therapy until after the 10th to 12th week of pregnancy, after the fetus’s organs have gone through their most rapid development. This delay may minimize any adverse effects of AZT on fetal development, but it needs to be balanced with the health of the mother and possible transmission of HIV to the fetus.

Most children with HIV became infected from their mothers near the time of birth. This means that for many babies, treatment can be started soon after birth. Federal guidelines recommend that all HIV-infected children younger than 1 year and all HIV-infected children of any age with symptoms of HIV infection or evidence of immune suppression be treated with anti-HIV drugs. For HIV-infected children with no symptoms, therapy can be deferred if risk of disease is considered low based on viral load and immune status.

Triple combination therapy can be used for all HIV-infected infants, children and adolescents treated with HIV drugs. Infants during the first six weeks of life who have been exposed to HIV but whose HIV status is unknown can be treated with AZT as sole therapy. Infants diagnosed with HIV while receiving AZT alone should be switched to combination therapy.

Though the AIDS death rate has dropped drastically, and educational efforts aimed at curbing the number of new HIV infections have had a small impact, experts say the next hurdles are to develop an AIDS-preventive vaccine and to create new therapies, such as ones that would effectively treat AIDS patients when drug-resistant strains of HIV develop. On both fronts, promising efforts are in progress.

For example, NIAID is conducting trials of three novel HIV vaccine approaches. One trial is testing a vaccine applied to spots such as the moist tissues lining the urinary and reproductive tracts. This is because most HIV infections, such as those acquired through sexual exposure, are transmitted across these “mucosal” sites. Researchers theorize that a vaccine that prompts the body to produce antibodies at these sites may have a protective effect against the AIDS virus.

Another vaccine approach is using common Salmonella bacteria to deliver HIV proteins in a way that may trigger the body to produce a better immune response. A third study is examining a cancer drug, GM-CSF, to determine its effect on stimulating immunity. NIAID also is experimenting with a vaccine approach that “neutralizes” antibodies to HIV, which then bind to the virus in a way that may prevent it from infecting cells.

A new class of drugs called fusion inhibitors has been shown in early trials to block HIV’s entry into cells, which may keep the virus from reproducing. These drugs hold particular promise for patients whose HIV viral loads have rebounded to elevated levels because the virus strains they carry have become resistant to triple combination therapy. Researchers reported at the 6th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic infections in February 1999 that one fusion inhibitor, T-20, significantly lowered virus amounts in a group of patients with drug-resistant viral strains.

Other therapies aimed at eradicating the virus that remains after successful combination treatment include drugs targeted at bolstering the immune system such as IL-2 (Interleukin-2) and G-CSF (Neupogen).

Though these and other potential treatments may individually or in combination help wipe out AIDS sometime in the future, what’s really needed, says NIAID’s Fauci, are types of drugs that don’t yet exist. “These agents would ideally be potent, inexpensive, relatively nontoxic even after prolonged periods, active against viral strains resistant to currently available agents, and easy to administer.”

Source: John Henkel. FDA Consumer, July-Aug 19