|

1. Basics |

|

v

Facts and Fallacies About Digestive Diseases

Researchers have only recently begun to understand the many, often complex diseases that affect the digestive system. Accordingly, people are gradually replacing folklore, old wivesí tales, and rumors about the causes and treatments of digestive diseases with accurate, up-to-date information. But misunderstandings still exist, and while some folklore is harmless, some can be dangerous if it keeps a person from correctly preventing or treating an illness. Listed below are some common misconceptions (fallacies), about digestive diseases, followed by the facts as professionals understand them today.

|

Ulcers

Spicy food and stress cause stomach ulcers.

False. The truth is, almost all stomach ulcers are caused either by infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) or by use of pain medications such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or

naproxen, the so-called nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Most H. pylori-related ulcers can be cured with antibiotics.

NSAID-induced ulcers can be cured with time, stomach-protective medications, antacids, and avoidance of

NSAIDs. Spicy food and stress may aggravate ulcer symptoms in some people, but they do not cause ulcers.

Ulcers can also be caused by cancer.

Heartburn

Smoking a cigarette helps relieve heartburn.

False. Actually, cigarette smoking contributes to heartburn. Heartburn occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter

(LES)-a muscle between the esophagus and stomach-relaxes, allowing the acidic contents of the stomach to splash back into the esophagus. Cigarette smoking causes the LES to relax.

|

|

Celiac disease is a rare childhood disease.

False. Celiac disease affects both children and adults. About 1 in 200 people in the United States have celiac disease. Sometimes celiac disease first causes symptoms during childhood, usually diarrhea, growth failure, and failure to thrive. But the disease can also first cause symptoms in adults of any age. These symptoms may be vague and therefore attributed to other conditions. Symptoms can include bloating, diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin rash, anemia, and thinning of the bones (osteoporosis). Celiac disease may cause such nonspecific symptoms for several years before being correctly diagnosed and treated.

People with celiac disease should not eat any foods containing gluten, a protein in wheat, rye, and barley, whether they have symptoms or not. In celiac disease, gluten destroys part of the lining of the small intestine, which interferes with the absorption of nutrients. Even a small amount of gluten can cause damage, and sometimes no symptoms will be apparent.

Bowel Regularity

Bowel regularity means a bowel movement every day.

False. The frequency of bowel movements among normal, healthy people varies from three a day to three a week, and some perfectly healthy people fall outside both ends of this range.

Constipation

Habitual use of enemas to treat constipation is harmless.

False. Habitual use of enemas is not harmless. Over time, enemas can impair the natural muscle action of the intestines, leaving them unable to function normally. An ongoing need for enemas is not normal; you should see a doctor if you find yourself relying on them or any other medication to have a bowel movement.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome is a disease.

True. Irritable bowel syndrome is a disease, although it is also called a functional disorder. Irritable bowel syndrome involves a problem in how the muscles in the intestines work and pain perception in the bowel. It is characterized by gas, abdominal pain, and diarrhea or constipation, or both. Although the syndrome can cause considerable pain and discomfort, it does not damage the digestive tract as organic diseases do. Also, irritable bowel syndrome does not lead to more serious digestive diseases later, such as cancer.

Diverticulosis

Diverticulosis is a serious but uncommon problem.

False. Actually, the majority

of Americans over age 60 have diverticulosis, but only a small

percentage have symptoms or complications. Diverticulosis is a condition in which little sacs or out-pouchings called diverticula develop in the wall of the colon. These sacs tend to appear and increase in number with age. Most people have no symptoms and learn that they have diverticula after an x ray or intestinal examination. Less than 10 percent of people with diverticulosis ever develop complications such as infection (diverticulitis), bleeding, or perforation of the colon.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease is caused by psychological problems.

False. Inflammatory bowel disease is the general name for two diseases that cause inflammation in the intestines, Crohnís disease and ulcerative colitis. The cause of the disease is unknown, but researchers speculate that it may be a virus or bacteria interacting with the bodyís immune system. No evidence has been found to support the theory that inflammatory bowel disease is caused by tension, anxiety, or any other psychological factor or disorder.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is caused only by alcoholism.

False. Alcoholism is just one of many causes of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is scarring and decreased function of the liver. In the United States, alcohol causes less than one-half of cirrhosis cases.

The remaining cases are from diseases that cause liver damage. For example, in children, cirrhosis may result from cystic fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, biliary atresia, glycogen storage disease, and other rare diseases. In adults, cirrhosis may be caused by hepatitis B or C, primary biliary cirrhosis, diseases of abnormal storage of metals like iron or copper in the body, severe reactions to prescription drugs, or injury to the ducts that drain bile from the liver. In adults, cirrhosis can also be caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is becoming the most common liver disease in the United States, affecting 2 to 5 percent of Americans.

Ostomy Surgery

After ostomy surgery, men have erectile dysfunction and women have impaired sexual function and are unable to become pregnant.

False. Ostomy surgery does not, in general, interfere with a personís sexual or reproductive capabilities. Ostomy surgery is a procedure in which the diseased part of the small or large intestine is removed and the remaining intestine is attached to an opening in the abdomen. Although some men who have had radical ostomy surgery for cancer lose the ability to achieve and sustain an erection, most men do not, or, if they do, it is temporary. If erectile dysfunction persists, a variety of solutions are available. A urologist, a doctor who specializes in such problems, can help find the best solution. In women, ostomy surgery does not damage sexual or reproductive organs, so it is not a direct cause of sexual problems or sterility.

Factors such as pain and the adjustment to a new body image may create temporary sexual problems, but they can usually be resolved with time and, in some cases, counseling. Unless a woman has had a hysterectomy to remove her uterus, she can still bear children.

v

Digestive Diseases

Statistics

|

|

Prevalence: 60 to 70 million people affected by all digestive diseases (1985)

|

|

|

Mortality: 191,000, including deaths from cancer (1985)

|

|

|

Hospitalizations: 10 million (13 percent of all hospitalizations) (1985)

|

|

|

Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: 6 million (14 percent of all procedures) (1987)

|

|

|

Physician office visits: 50 million (1985)

|

|

|

Disability: 1.4 million people (1987)

|

|

|

Costs:

|

|

|

$107 billion (1992)

|

|

|

$87 billion direct medical costs

|

|

|

$20 billion indirect costs (e.g., disability and mortality)

|

Specific Diseases

Abdominal Wall Hernia

Incidence: 800,000 new cases, including 500,000 inguinal hernias (1985) Incidence: 800,000 new cases, including 500,000 inguinal hernias (1985)

Prevalence: 4.5 million people (1988-90) Prevalence: 4.5 million people (1988-90)

Hospitalizations: 640,000 (1980) Hospitalizations: 640,000 (1980)

Physician office visits: 2 to 3 million (1989-90) Physician office visits: 2 to 3 million (1989-90)

Prescriptions: 184,000 (1989-90) Prescriptions: 184,000 (1989-90)

Disability: 550,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 550,000 people (1983-87)

Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis

Prevalence: 400,000 people (1976-80) Prevalence: 400,000 people (1976-80)

Mortality: 26,050 deaths (1987) Mortality: 26,050 deaths (1987)

Hospitalizations: 300,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 300,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 1 million (1985) Physician office visits: 1 million (1985)

Disability: 112,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 112,000 people (1983-87)

Constipation

Prevalence: 4.4 million people (1983-87) Prevalence: 4.4 million people (1983-87)

Mortality: 29 deaths (1982-85) Mortality: 29 deaths (1982-85)

Hospitalizations: 100,000 (1983-87) Hospitalizations: 100,000 (1983-87)

Physician office visits: 2 million (1985) Physician office visits: 2 million (1985)

Prescriptions: 1 million (1985) Prescriptions: 1 million (1985)

Disability: 13,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 13,000 people (1983-87)

Diverticular Disease

Incidence: 300,000 new cases (1987) Incidence: 300,000 new cases (1987)

Prevalence: 2 million people (1983-87) Prevalence: 2 million people (1983-87)

Mortality: 3,000 deaths (1985) Mortality: 3,000 deaths (1985)

Hospitalizations: 440,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 440,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 2 million (1987)

Physician office visits: 2 million (1987)

Disability: 112,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 112,000 people (1983-87)

Gallstones

Prevalence: 16 to 22 million people (1976-87) Prevalence: 16 to 22 million people (1976-87)

Mortality: 2,975 (1985) Mortality: 2,975 (1985)

Hospitalizations: 800,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 800,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 600,000 to 700,000 (1985) Physician office visits: 600,000 to 700,000 (1985)

Prescriptions: 195,000 (1985) Prescriptions: 195,000 (1985)

Surgical procedures: 500,000 cholecystectomies (1987) Surgical procedures: 500,000 cholecystectomies (1987)

Disability: 48,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 48,000 people (1983-87)

Gastritis and Nonulcer Dyspepsia (NUD)

Incidence: Incidence:

Gastritis: 313,000 new cases (1975) Gastritis: 313,000 new cases (1975)

Chronic NUD: 444,000 new cases (1975) Chronic NUD: 444,000 new cases (1975)

Acute NUD: 8.2 million new cases (1988) Acute NUD: 8.2 million new cases (1988)

Prevalence: Prevalence:

Gastritis: 2.7 million people (1988) Gastritis: 2.7 million people (1988)

NUD: 5.8 million people (1988) NUD: 5.8 million people (1988)

Mortality: Mortality:

Gastritis: 703 (1980ís) Gastritis: 703 (1980ís)

NUD: 49 (1980ís) NUD: 49 (1980ís)

Hospitalizations: Hospitalizations:

Gastritis: 600 (1980ís) Gastritis: 600 (1980ís)

NUD: 65,000 (1980ís) NUD: 65,000 (1980ís)

Physician office visits: Physician office visits:

Gastritis: 3 million (1980ís) Gastritis: 3 million (1980ís)

NUD: 800,000 (1980ís) NUD: 800,000 (1980ís)

Prescriptions: Prescriptions:

Gastritis: 2 million (1985) Gastritis: 2 million (1985)

NUD: 649,000 (1985) NUD: 649,000 (1985)

Disability: Disability:

Gastritis: 34,000 people (1983-87)

Gastritis: 34,000 people (1983-87)

Chronic NUD: 42,000 people (1983-87) Chronic NUD: 42,000 people (1983-87)

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Related Esophageal Disorders

Prevalence: 3 to 7 percent of U.S. population (1985) Prevalence: 3 to 7 percent of U.S. population (1985)

Mortality: 1,000 deaths (1984-88) Mortality: 1,000 deaths (1984-88)

Hospitalizations: 1 million (1985) Hospitalizations: 1 million (1985)

Physician office visits: 4 to 5 million (1985) Physician office visits: 4 to 5 million (1985)

Hemorrhoids (1983-87)

Incidence: 1 million new cases Incidence: 1 million new cases

Prevalence: 10.4 million people Prevalence: 10.4 million people

Mortality: 17 deaths Mortality: 17 deaths

Hospitalizations: 316,000 Hospitalizations: 316,000

Physician office visits: 3.5 million Physician office visits: 3.5 million

Prescriptions: 1.5 million Prescriptions: 1.5 million

Disability: 52,000 people Disability: 52,000 people

Infectious Diarrhea

Incidence: 99 million new cases (1980) Incidence: 99 million new cases (1980)

Mortality: 3,100 deaths (1985) Mortality: 3,100 deaths (1985)

Hospitalizations: 462,000 to 728,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 462,000 to 728,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 8 to 12 million (1985) Physician office visits: 8 to 12 million (1985)

Prescriptions: 5 to 8 million (1985) Prescriptions: 5 to 8 million (1985)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (1987)

Incidence: 2 to 6 new cases per 100,000 people Incidence: 2 to 6 new cases per 100,000 people

Prevalence: 300,000 to 500,000 people Prevalence: 300,000 to 500,000 people

Mortality: Fewer than 1,000 deaths Mortality: Fewer than 1,000 deaths

Hospitalizations: 100,000 (64 percent for Crohnís disease) Hospitalizations: 100,000 (64 percent for Crohnís disease)

Physician office visits: 700,000 Physician office visits: 700,000

Disability: 119,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 119,000 people (1983-87)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Prevalence: 5 million people (1987) Prevalence: 5 million people (1987)

Hospitalizations: 34,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 34,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 3.5 million (1987) Physician office visits: 3.5 million (1987)

Prescriptions: 2.2 million (1985) Prescriptions: 2.2 million (1985)

Disability: 400,000 people (1983-87)

Disability: 400,000 people (1983-87)

Lactose Intolerance [2]

Prevalence: 30 to 50 million people (1994) Prevalence: 30 to 50 million people (1994)

Pancreatitis

Incidence: Acute: 17 new cases per 100,000 people (1976-88) Incidence: Acute: 17 new cases per 100,000 people (1976-88)

Mortality: 2,700 deaths (1985) Mortality: 2,700 deaths (1985)

Hospitalizations: Hospitalizations:

Acute: 125,000 (1987) Acute: 125,000 (1987)

Chronic: 20,000 (1987) Chronic: 20,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: Physician office visits:

Acute: 911,000 (1987) Acute: 911,000 (1987)

Chronic: 122,000 (1987) Chronic: 122,000 (1987)

Peptic Ulcer

Prevalence: 5 million people (1987) Prevalence: 5 million people (1987)

Mortality: 6,500 deaths (1987) Mortality: 6,500 deaths (1987)

Hospitalizations: 630,000 (1987) Hospitalizations: 630,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 3 to 5 million (1985) Physician office visits: 3 to 5 million (1985)

Prescriptions: 2 million (1985) Prescriptions: 2 million (1985)

Disability: 401,000 people (1983-87) Disability: 401,000 people (1983-87)

Viral Hepatitis

Incidence: Incidence:

Hepatitis A: 32,000 new cases (1992) Hepatitis A: 32,000 new cases (1992)

Hepatitis B: 200,000 to 300,000 new cases (1990) Hepatitis B: 200,000 to 300,000 new cases (1990)

Hepatitis C: 150,000 new cases (1991) Hepatitis C: 150,000 new cases (1991)

Hepatitis D: 70,000 new cases (1990) Hepatitis D: 70,000 new cases (1990)

Prevalence: Prevalence:

Hepatitis A: 32 to 38 percent of U.S. population that have any history of disease (1991) Hepatitis A: 32 to 38 percent of U.S. population that have any history of disease (1991)

Hepatitis B: 4 percent of U.S. population that have any history of disease (1990) Hepatitis B: 4 percent of U.S. population that have any history of disease (1990)

Hepatitis C and D: Not determined Hepatitis C and D: Not determined

Mortality: Fewer than 1,000 deaths (1985) Mortality: Fewer than 1,000 deaths (1985)

Hospitalizations: 33,000 (1987)

Hospitalizations: 33,000 (1987)

Physician office visits: 500,000 (1985) Physician office visits: 500,000 (1985)

Additional Data

Liver Transplants 3: 3,300 transplants performed (1993)

Number of gastroenterologists in the United States 4: 7,493 (1990)

Sources

1. Unless noted, the data in this fact sheet are from:

Everhart, J. E. (Ed.). (1994). Digestive diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and impact. (NIH Publication No. 94-1447). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

The book answers hundreds of questions about the scope and impact of the major infectious, chronic, and malignant digestive diseases. National and special-population-based data on specific digestive diseases provide information about the prevalence, incidence, medical care, disability, mortality, and research needs. The data were compiled primarily from the surveys of the National Center for Health Statistics, supplemented by other Federal agencies and private sources.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

3. United Network for Organ Sharing Scientific Registry.

4. American Medical Association. (1992). Physician characteristics and distribution in the United States (1992

ed., p. 20). Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

Data for digestive diseases as a group and for specific diseases are provided in various categories. For some diseases, data do not exist in all categories. Following are definitions of the categories as used in this fact sheet:

|

|

Disability: The number of people in a year whose ability to perform major daily activities such as working, housekeeping, and going to school is limited and reduced over long periods because of a disease.

|

|

|

Hospitalizations: The number of hospitalizations for a disease in a year.

|

|

|

Incidence: The number of new cases of a disease in the U.S. population in a year.

|

|

|

Mortality: The number of deaths resulting from the disease listed as the underlying or primary cause in a year.

|

|

|

Physician office visits: The number of outpatient visits to office-based physicians for a disease in a year.

|

|

|

Prescriptions: The number of prescriptions written annually for medications to treat a specific disease.

|

|

|

Prevalence: The number of people in the United States affected by a disease or diseases in a year.

|

|

|

Procedures: The number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures performed annually in a hospital setting.

|

v

Your Digestive System and How It Works

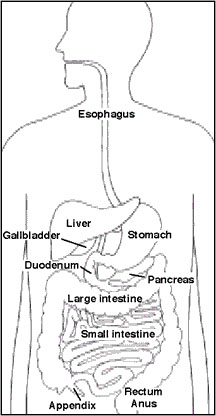

The digestive system is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus (see figure). Inside this tube is a lining called the mucosa. In the mouth, stomach, and small intestine, the mucosa contains tiny glands that produce juices to help digest food.

Two solid organs, the liver and the pancreas, produce digestive juices that reach the intestine through small tubes. In addition, parts of other organ systems (for instance, nerves and blood) play a major role in the digestive system.

Why is digestion important?

When we eat such things as bread, meat, and vegetables, they are not in a form that the body can use as nourishment. Our food and drink must be changed into smaller molecules of nutrients before they can be absorbed into the blood and carried to cells throughout the body. Digestion is the process by which food and drink are broken down into their smallest parts so that the body can use them to build and nourish cells and to provide energy.

How is food digested?

Digestion involves the mixing of food, its movement through the digestive tract, and the chemical breakdown of the large molecules of food into smaller molecules. Digestion begins in the mouth, when we chew and swallow, and is completed in the small intestine. The chemical process varies somewhat for different kinds of food.

|

Movement of Food Through the System

The large, hollow organs of the digestive system contain muscle that enables their walls to move. The movement of organ walls can propel food and liquid and also can mix the contents within each organ. Typical movement of the esophagus, stomach, and intestine is called peristalsis. The action of peristalsis looks like an ocean wave moving through the muscle. The muscle of the organ produces a narrowing and then propels the narrowed portion slowly down the length of the organ. These waves of narrowing push the food and fluid in front of them through each hollow organ.

The first major muscle movement occurs when food or liquid is swallowed. Although we are able to start swallowing by choice, once the swallow begins, it becomes involuntary and proceeds under the control of the nerves.

The esophagus is the organ into which the swallowed food is pushed. It connects the throat above with the stomach below. At the junction of the esophagus and stomach, there is a ringlike valve closing the passage between the two organs. However, as the food approaches the closed ring, the surrounding muscles relax and allow the food to pass.

|

|

The food then enters the stomach, which has three mechanical tasks to do. First, the stomach must store the swallowed food and liquid. This requires the muscle of the upper part of the stomach to relax and

accept large volumes of swallowed material. The second job is to mix up the food, liquid, and digestive juice produced by the stomach. The lower part of the stomach mixes these materials by its muscle action. The third task of the stomach is to empty its contents slowly into the small intestine.

Several factors affect emptying of the stomach, including the nature of the food (mainly its fat and protein content) and the degree of muscle action of the emptying stomach and the next organ to receive the contents (the small intestine). As the food is digested in the small intestine and dissolved into the juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine, the contents of the intestine are mixed and pushed forward to allow further digestion.

Finally, all of the digested nutrients are absorbed through the intestinal walls. The waste products of this process include undigested parts of the food, known as fiber, and older cells that have been shed from the mucosa. These materials are propelled into the colon, where they remain, usually for a day or two, until the feces are expelled by a bowel movement.

Production of Digestive Juices

The glands that act first are in the mouth - the salivary glands. Saliva produced by these glands contains an enzyme that begins to digest the starch from food into smaller molecules.

The next set of digestive glands is in the stomach lining. They produce stomach acid and an enzyme that digests protein. One of the unsolved puzzles of the digestive system is why the acid juice of the stomach does not dissolve the tissue of the stomach itself. In most people, the stomach mucosa is able to resist the juice, although food and other tissues of the body cannot.

After the stomach empties the food and juice mixture into the small intestine, the juices of two other digestive organs mix with the food to continue the process of digestion. One of these organs is the pancreas. It produces a juice that contains a wide array of enzymes to break down the carbohydrate, fat, and protein in food. Other enzymes that are active in the process come from glands in the wall of the intestine or even a part of that wall.

The liver produces yet another digestive juice-bile. The bile is stored between meals in the gallbladder. At mealtime, it is squeezed out of the gallbladder into the bile ducts to reach the intestine and mix with the fat in our food. The bile acids dissolve the fat into the watery contents of the intestine, much like detergents that dissolve grease from a frying pan. After the fat is dissolved, it is digested by enzymes from the pancreas and the lining of the intestine.

Absorption and Transport of Nutrients

Digested molecules of food, as well as water and minerals from the diet, are absorbed from the cavity of the upper small intestine. Most absorbed materials cross the mucosa into the blood and are carried off in the bloodstream to other parts of the body for storage or further chemical change. As already noted, this part of the process varies with different types of nutrients.

|

|

Carbohydrates. It is recommended that about 55 to 60 percent of total daily calories be from carbohydrates. Some of our most common foods contain mostly carbohydrates. Examples are bread, potatoes, legumes, rice, spaghetti, fruits, and vegetables. Many of these foods contain both starch and fiber.

The digestible carbohydrates are broken into simpler molecules by enzymes in the saliva, in juice produced by the pancreas, and in the lining of the small intestine. Starch is digested in two steps: First, an

enzyme in the saliva and pancreatic juice breaks the starch into molecules called maltose; then an enzyme in the lining of the small intestine (maltase) splits the maltose into glucose molecules that can be absorbed into the blood. Glucose is carried through the bloodstream to the liver, where it is stored or used to provide energy for the work of the body.

|

Table sugar is another carbohydrate that must be digested to be useful. An enzyme in the lining of the small intestine digests table sugar into glucose and fructose, each of which can be absorbed from the intestinal cavity into the blood. Milk contains yet another type of sugar, lactose, which is changed into absorbable molecules by an enzyme called lactase, also found in the intestinal lining.

|

|

Protein. Foods such as meat, eggs, and beans consist of giant molecules of protein that must be digested by enzymes before they can be used to build and repair body tissues. An enzyme in the juice of the stomach starts the digestion of swallowed protein. Further digestion of the protein is completed in the small intestine. Here, several enzymes from the pancreatic juice and the lining of the intestine carry out the breakdown of huge protein molecules into small molecules called amino acids. These small molecules can be absorbed from the hollow of the small intestine into the blood and then be carried to all parts of the body to build the walls and other parts of cells.

|

|

|

Fats. Fat molecules are a rich source of energy for the body. The first step in digestion of a fat such as butter is to dissolve it into the watery content of the intestinal cavity. The bile acids produced by the liver act as natural detergents to dissolve fat in water and allow the enzymes to break the large fat molecules into smaller molecules, some of which are fatty acids and cholesterol. The bile acids combine with the fatty acids and cholesterol and help these molecules to move into the cells of the

mucosa. In these cells the small molecules are formed back into large molecules, most of which pass into vessels (called

lymphatics) near the intestine. These small vessels carry the reformed fat to the veins of the chest, and the blood carries the fat to storage depots in different parts of the body.

|

|

|

Vitamins. Another vital part of our food that is absorbed from the small intestine is the class of chemicals we call vitamins. The two different types of vitamins are classified by the fluid in which they can be dissolved: water-soluble vitamins (all the B vitamins and vitamin C) and fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, and K).

|

|

|

Water and salt. Most of the material absorbed from the cavity of the small intestine is water in which salt is dissolved. The salt and water come from the food and liquid we swallow and the juices secreted by the many digestive glands.

|

How is the digestive process controlled?

Hormone Regulators

A fascinating feature of the digestive system is that it contains its own regulators. The major hormones that control the functions of the digestive system are produced and released by cells in the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine. These hormones are released into the blood of the digestive tract, travel back to the heart and through the arteries, and return to the digestive system, where they stimulate digestive juices and cause organ movement.

The hormones that control digestion are gastrin, secretin, and cholecystokinin (CCK):

|

|

Gastrin causes the stomach to produce an acid for dissolving and digesting some foods. It is also necessary for the normal growth of the lining of the stomach, small intestine, and colon.

|

|

|

Secretin causes the pancreas to send out a digestive juice that is rich in bicarbonate. It stimulates the stomach to produce pepsin, an enzyme that digests protein, and it also stimulates the liver to produce bile.

|

|

|

CCK causes the pancreas to grow and to produce the enzymes of pancreatic juice, and it causes the gallbladder to empty.

|

Additional hormones in the digestive system regulate appetite:

|

|

Ghrelin is produced in the stomach and upper intestine in the absence of food in the digestive system and stimulates appetite.

|

|

|

Peptide YY is produced in the GI tract in response to a meal in the system and inhibits appetite.

|

Both of these hormones work on the brain to help regulate the intake of food for energy.

Nerve Regulators

Two types of nerves help to control the action of the digestive system. Extrinsic (outside) nerves come to the digestive organs from the unconscious part of the brain or from the spinal cord. They release a chemical called acetylcholine and another called adrenaline. Acetylcholine causes the muscle of the digestive organs to squeeze with more force and increase the

-push- of food and juice through the digestive tract. Acetylcholine also causes the stomach and pancreas to produce more digestive juice. Adrenaline relaxes the muscle of the stomach and intestine and decreases the flow of blood to these

organs

.

Even more important, though, are the intrinsic (inside) nerves, which make up a very dense network embedded in the walls of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon. The intrinsic nerves are triggered to act when the walls of the hollow organs are stretched by food. They release many different substances that speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of juices by the digestive organs.

v

Smoking and Your Digestive System

Cigarette smoking causes a variety of life-threatening diseases, including lung cancer, emphysema, and heart disease. An estimated 430,000 deaths each year are directly caused by cigarette smoking. Smoking is responsible for changes in all parts of the body, including the digestive system. This fact can have serious consequences because it is the digestive system that converts foods into the nutrients the body needs to live.

Current estimates indicate that about one-third of all adults smoke. And, while adult men seem to be smoking less, women and teenagers of both sexes seem to be smoking more. How does smoking affect the digestive system of all these people?

Harmful Effects

Smoking has been shown to have harmful effects on all parts of the digestive system, contributing to such common disorders as heartburn and peptic ulcers. It also increases the risk of Crohnís disease and possibly gallstones. Smoking seems to affect the liver, too, by changing the way it handles drugs and alcohol. In fact, there seems to be enough evidence to stop smoking solely on the basis of digestive distress.

Heartburn

Heartburn is common among Americans. More than 60 million Americans have heartburn at least once a month, and about 15 million have it daily.

Heartburn happens when acidic juices from the stomach splash into the esophagus. Normally, a muscular valve at the lower end of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), keeps the acid solution in the stomach and out of the esophagus. Smoking decreases the strength of the esophageal valve, thereby allowing stomach acids to reflux, or flow backward into the esophagus.

Smoking also seems to promote the movement of bile salts from the intestine to the stomach, which makes the stomach acids more harmful. Finally, smoking may directly injure the esophagus, making it less able to resist further damage from refluxed fluids.

Peptic Ulcer

A peptic ulcer is an open sore in the lining of the stomach or duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The exact cause of ulcers is not known. A relationship between smoking cigarettes and ulcers, especially duodenal ulcers, does exist. The 1989 Surgeon Generalís report stated that ulcers are more likely to occur, less likely to heal, and more likely to cause death in smokers than in nonsmokers.

Why is this so? Doctors are not really sure, but smoking does seem to be one of several factors that work together to promote the formation of ulcers.

For example, some research suggests that smoking might increase a personís risk of infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Most peptic ulcers are caused by this bacterium.

Stomach acid is also important in producing ulcers. Normally, most of this acid is buffered by the food we eat. Most of the unbuffered acid that enters the duodenum is quickly neutralized by sodium bicarbonate, a naturally occurring alkali produced by the pancreas. Some studies show that smoking reduces the bicarbonate produced by the pancreas, interfering with the neutralization of acid in the

duodenum. Other studies suggest that chronic cigarette smoking may increase the amount of acid secreted by the stomach.

Whatever causes the link between smoking and ulcers, two points have been repeatedly demonstrated: People who smoke are more likely to develop an ulcer, especially a duodenal ulcer, and ulcers in smokers are less likely to heal quickly in response to otherwise effective treatment. This research tracing the relationship between smoking and ulcers strongly suggests that a person with an ulcer should stop smoking.

Liver Disease

The liver is an important organ that has many tasks. Among other things, the liver is responsible for processing drugs, alcohol, and other toxins to remove them from the body. There is evidence that smoking alters the ability of the liver to handle such substances. In some cases, this may influence the dose of medication necessary to treat an illness. Some research also suggests that smoking can aggravate the course of liver disease caused by excessive alcohol intake.

Crohnís Disease

Crohnís disease causes inflammation deep in the lining of the intestine. The disease, which causes pain and diarrhea, usually affects the small intestine, but it can occur anywhere in the digestive tract. Research shows that current and former smokers have a higher risk of developing Crohnís disease than nonsmokers do. Among people with the disease, smoking is associated with a higher rate of relapse, repeat surgery, and immunosuppressive treatment. In all areas, the risk for women, whether current or former smokers, is slightly higher than for men. Why smoking increases the risk of Crohnís disease is unknown, but some theories suggest that smoking might lower the intestineís defenses, decrease blood flow to the intestines, or cause immune system changes that result in inflammation.

Gallstones

Several studies suggest that smoking may increase the risk of developing gallstones and that the risk may be higher for women. However, research results on this topic are not consistent, and more study is needed.

Can the damage be reversed?

Some of the effects of smoking on the digestive system appear to be of short duration. For example, the effect of smoking on bicarbonate production by the pancreas does not appear to last. Within a half-hour after smoking, the production of bicarbonate returns to normal. The effects of smoking on how the liver handles drugs also disappear when a person stops smoking. However, people who no longer smoke still remain at risk for Crohnís disease. Clearly, this question needs more study.

For more information

American Liver Foundation (ALF)

75 Maiden Lane, Suite 603

New York, NY 10038-4810

Phone: 1-800-GO-LIVER (465-4837),

1-888-4HEP-USA (443-7872), or (212) 668-1000

Fax: (212) 483-8179

Email: info@liverfoundation.org

Internet: www.liverfoundation.org

Celiac Disease Foundation

13251 Ventura Boulevard, Suite 1

Studio City, CA 91604-1838

Phone: (818) 990-2354

Fax: (818) 990-2379

Email: cdf@celiac.org

Internet: www.celiac.org

Crohnís & Colitis Foundation of America Inc.

386 Park Avenue South, 17th Floor

New York, NY 10016-8804

Phone: 1-800-932-2423 or (212) 685-3440

Fax: (212) 779-4098

Email: info@ccfa.org

Internet: www.ccfa.org

Hepatitis Foundation International

504 Blick Drive

Silver Spring, MD 20904-2901

Phone: 1-800-891-0707 or (301) 662-4200

Fax: (301) 622-4702

Email: HFI@comcast.net

Internet: www.hepfi.org

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Inc.

P.O. Box 170864

Milwaukee, WI 53217-8076

Phone: 1-888-964-2001 or (414) 964-1799

Fax: (414) 964-7176

Email: iffgd@iffgd.org

Internet: www.iffgd.org

United Ostomy Association Inc.

19772 MacArthur Boulevard, Suite 200

Irvine, CA 92612-2405

Phone: 1-800-826-0826 or (949) 660-8624

Fax: (949) 660-9262

Email: info@uoa.org

Internet: www.uoa.org

Office on Smoking and Health

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Mail Stop K-50

4770 Buford Highway NE.

Atlanta, GA 30341-3717

Phone: 1-800-CDC-1311 (232-1311)

Fax: 1-888-CDC-FAXX (888-232-3299)

Email: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Internet: www.cdc.gov/tobacco |

|