| Contents | Previous | Next |

Guideline: The primary risk factor for suicide in both the general and clinical populations is a psychiatric diagnosis. An active or chronic general medical disease is also a significant risk factor. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

There are approximately seven suicide attempts for every completed suicide, and about 2 to 3 percent of those who attempt suicide go on to complete suicide. In the general population, the single most reliable risk factor for completed suicide is a psychiatric diagnosis. Other risk factors are being Caucasian, male, and elderly. Roughly 25 percent of all suicides occur in the elderly, though they constitute only 10 percent of the general population. Elderly men continue to have the highest suicide rates, even though the rates among male youths are increasing.

As in the general population, the primary risk factor for suicide in clinical populations is a psychiatric diagnosis. Male gender is less significant than in the general population, but being Caucasian remains an important risk factor. The middle years seem to have increased risk in patient populations, while higher rates are found in the elderly and youths in the general population. The period of highest risk is during hospitalization or immediately after discharge.

The suicide literature on both general and clinical populations consistently reveals the risk factors of depression, alcohol or drug abuse, and psychosis (psychotic depression, mania, or schizophrenia). The presence of general medical disorders is a risk factor in the general population, but is not always evaluated in clinical studies. Approximately 70 percent of suicide completers have one or more active or chronic medical illnesses at the time of death. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) has recently been reported to carry a high suicide risk as well. To summarize, the following risk factors have been empirically related to suicide:

Many patients with suicidal ideation can be managed as outpatients if they are not psychotic, if they do not abuse substances to a significant extent, and if they themselves feel that they can control their suicidal ideations or impulses, based on direct discussions about their thoughts of suicide. A few general principles for managing the patient with suicidal ideation are suggested by the panel, based on current clinical practice, logic, panel consensus, and knowledge of risk factors.

The practitioner is advised to:

The practitioner is advised to consider hospitalization for suicidal patients if:

For outpatient management, the practitioner is advised to:

Guideline: Depression in the elderly should not routinely be ascribed to demoralization or “normal sadness” over financial barriers, medical problems, or other concerns. The general principles for treatment of adults with major depressive disorder apply as well to elderly patients. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

The diagnosis of late-life depression must be given particular attention. The prevalence of major depressive disorder may be lower in the elderly than in nonelderly adults, which suggests that aging per se is not an etiological factor in depression. In elderly patients with recurrent depression, the possibility of bipolar disorder must be considered. Other psychiatric disorders to be considered in the differential diagnosis include early dementia, delusional disorders, organic (secondary) disorders, and substance-induced mood disorders. Finally, the first onset of primary major depressive disorder past the age of 50 is uncommon and often related to a specific medical etiology. A particularly careful medical evaluation is often needed in these patients.

The efficacy of the various treatments for depression in the elderly is, by and large, equal to that found in adults in general. The differences in dealing with the elderly are the particular practical problems that they and the treatments confront. These problems require more strategic planning and somewhat different tactics (e.g., more likely use of blood level determinations, particular care in minimizing side effects). Treatment of late-life major depressive disorder was reviewed by an NIMH Consensus Development Conference (1991), the general conclusions of which are entirely consistent with these guidelines. The consequences of unrecognized and untreated depression in the elderly include increased health services utilization, longer hospital stays, poor treatment compliance, and increased morbidity and mortality from medical illness and suicide. The costs of treatment are relatively modest and can be minimized by careful monitoring of the patient’s clinical status.

In general, major depressive disorder in late life is a treatable illness. The evidence for the specific efficacy of medication is strongly based on randomized placebo-controlled trials. The evidence for the efficacy of psychotherapy alone as a treatment for less severely ill, nonpsychotic outpatients is beginning to accumulate, though this area remains understudied. Electroconvulsive therapy appears to be as effective in geriatric patients with severe or psychotic major depressive disorder as in nongeriatric groups. Evidence for or against the efficacy of combined ecu phase treatment is generally lacking in geriatric patients, but studies are currently under way. One preliminary analysis (based on intent-to-treat samples) found that interpersonal psychotherapy and nortriptyline, within the context of a supportive, psychoeducationally oriented milieu, achiever a treatment success rate of around 75 percent in acute phase treatment (Reynolds, Frank, Perel, et al., 1992). Finally, the utility of maintenance phase medication is suggested by a few studies.

Nearly all randomized controlled treatment trials in elderly depressed individuals to date have been conducted in the otherwise medically healthy. These patients are not representative of all depressed elderly. In fact, other nonpsychiatric medical conditions are risk factors for depression. Thus, in recommending treatments, the panel is assuming that those treatments effective in the depressed, but otherwise healthy, elderly will be effective in those with other concurrent medical conditions. However, the presence of such medical conditions appears to be a risk factor for a poorer prognosis in younger depressed patients (Keitner, Rya’ Miller, et al., 1991).

The problems of treating depression in the elderly can be complex an challenging, particularly with the high rate of co-morbid medical disorder Although treatment appears helpful for the depressed elderly, a pressing need remains for further controlled intervention research for depressions late in life, especially in patients with depressive disorders occurring in association with other nonpsychiatric medical and necrologic disorders.

Several obstacles or special risks confound treatment of the elderly (Table 15). Pharmacotherapy in elderly depressed patients is complicated by:

To provide optimal pharmacotherapy in elderly patients taking other medications or who have other nonpsychiatric medical disorders, the practitioner may need to rely on repeated plasma antidepressant drug level determinations, as the other medications and/or disorders can alter antidepressant absorption or metabolism. Because of the natural metabolic slowing that accompanies aging, blood level monitoring may be advisable in otherwise healthy elderly patients, particularly where therapeutic ranges are better established.

Table 15. Confounds in the diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly

|

Psychosocial difficulties that may interfere with optimal treatment response include:

General clinical management or a formal psychotherapy may be equally helpful in addressing these psychosocial obstacles. Social casework, particularly during acute treatment, to remove or modify “real life” obstacles to recovery may be helpful. However, the efficacy of social casework in those with major depressive disorder has not been formally tested. Regular contacts with family members during periods of individual crisis may also be useful.

The use of stimulant medications in the elderly was recently reviewed by an NIMH Consensus Development Conference (1991). While no randomized controlled trials were available, 8 to 12 open trials conducted over the last 3 decades, as well as clinical experience of psychopharmacologists who are expert in the treatment of the depressed elderly, suggest some efficacy and a low abuse potential for stimulant medications (NIMH, 1991). The panel does not recommend the routine use of stimulants in depressed elderly patients, given the availability of antidepressants with more predictable and established efficacy and sideeffect profiles. However, stimulants may be an option for highly selected elderly patients who have not responded to adequate trials of other treatments. A psychopharmacologic consultation is mandated before selection of this treatment.

Guideline: Light therapy is a treatment consideration only for well-documented mild to moderate seasonal, nonpsychotic, winter depressive episodes in patients with recurrent major depressive or bipolar II disorders or milder seasonal episodes. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

Light therapy is a relatively new treatment that has been tested in randomized trials for up to 2 weeks in patients with seasonal mood disorders, nearly always those with winter depressions (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). Its longer term efficacy has not been formally evaluated, though case reports and clinical experience suggest efficacy throughout the winter and in subsequent episodes. In addition, light therapy has not been tested against other potentially active treatments, such as medication, psychotherapy, or the combination, so whether seasonal depressions respond to these alternative treatments is unknown. Case reports suggest some efficacy for selected antidepressants. Since many patients with major depressive episodes occurring in a seasonal pattern have bipolar II or recurrent major depressive disorder, it is logical to believe that medication will be effective.

Given the current modest knowledge about light therapy and continuing research into the optimal method of administration, long-term safety, and other practical issues, the panel suggests the following principles:

Since the underlying mechanisms implicated in the seasonal pattern are not likely to be remedied by psychotherapy alone and there is no evidence to date for its efficacy, formal psychotherapy is not recommended as a first-line approach for truly seasonal depressions. Logically, light therapy should not be used as an adjunct to medication until either one alone has been optimally used. Light therapy can be useful to augment the response (if partial) to antidepressant medication and vice versa.

As with any treatment, the patient’s response should be closely monitored. Response to light therapy can be rapid (4 to 7 days), but for some, response may be delayed to 2 weeks. However, the placebo response rate may be significant as well. Therefore, one or several “extended evaluation” visits may be useful in identifying those in whom symptoms persist. Caution is urged in the use of light therapy with patients with specific ophthalmologic or other conditions (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). Since safety and efficacy have not been fully established beyond 2 weeks, consultation with a specialist may be helpful in determining specific risks and benefits for particular patients. Further information is available for interested practitioners (see Oren and Rosenthal, 1992; Terman, Williams, and Terman, 1991).

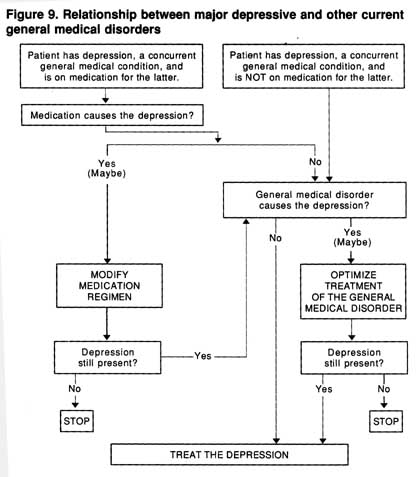

Guideline: If a patient has a depressive episode thought to be biologically caused by a concurrent general medical disorder, the practitioner is advised to (1) treat optimally the associated general medical condition, (2) reevaluate the patient’s condition, and (3) treat the major depression as an independent disorder if it is still present. In some cases, treatment of the major depression may need to proceed along with efforts to optimize treatment for the general medical disorder. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

As noted in Volume 1 of Depression in Primary Care, Detection and Diagnosis, the incidence of a major depressive episode at some time in the course of several other medical conditions (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, diabetes) is around 25 percent. Similar percentages may be expected for other nonpsychiatric medical conditions. The general strategy in such cases is to treat the medical condition first, since depression can be an unwanted direct effect of either the illness or its treatment, to reevaluate the patient’s condition for continued depression, and to treat the major depression as an independent disorder if it is still present (Hall, Popkin, Devaul, et al., 1978) (Figure 9). However, in some cases, the major depression is sufficiently severe or disabling that treatment for it is indicated while the general medical condition is being treated.

There are insufficient studies to recommend one medication over another solely on the basis of efficacy data. The side-effect and pharmacologic profiles of the antidepressant, patient age, prior response to specific antidepressants, family history of response to an antidepressant, and drug-drug interactions are among the many factors that must be weighed by a clinician when choosing a particular medication. The efficacy of psychotherapy is suggested by some open studies (see Watson, 1983, for a review) and by 20 randomized controlled trials for patients with cancer and depression (Depression Guideline Panel forthcoming), but predictors of response are not well defined. Those with low emotional support and pessimism who are widowed or divorced may particularly benefit from psychotherapy (Weisman and Worden, 1976-77). An empirical treatment trial with careful assessment of outcome (lust as with major depressive disorder not associated with a general medical illness) is recommended. Further research in this area is sorely needed to determine which patients should be treated with which therapy and to establish with greater certainty the efficacy of various treatments.

Figure 9. Relationship between major depressive and other current general medical disorders

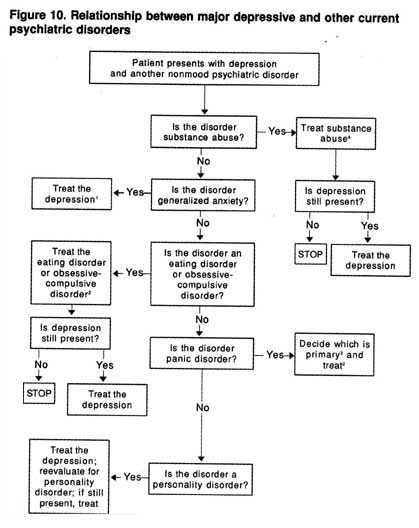

Guideline: When major depressive disorder co-occurs with another psychiatric disorder, the practitioner has three options: (1) to treat the major depressive disorder as the primary target and reevaluate the patient’s condition once he or she has responded to determine whether additional treatment is needed for the associated condition (e.g., as in major depressive disorder with personality disorder or generalized anxiety disorder), (2) to treat the associated condition as the initial treatment focus (e.g., as in concurrent major depression and anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or substance abuse), or (3) to attempt to decipher which condition is “primary” an select it as the initial treatment target (e.g., as in cases of major depressive and panic disorder). The option selected will depend on th’ nature of the concurrent disorder. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

Figure 10 provides an overview of the strategic choices that the practitioner confronts when depression occurs with other psychiatric or substance abuse problems.

The reasons to treat major depression as the primary target for those with concurrent generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are:

Available data on treating major depression when it is associated with a personality disorder suggest the following:

The rationale for treating concomitant obsessive-compulsive disorder,bulimia, anorexia, or substance abuse as the primary treatment target includes the following:

Figure 10. Relationship between major depressive disorder and other current psichiatric disorders

1When the depression is treated, the anxiety disorder should resolve as well.

2Choose medications known to be effective for both the depression and other psychiatric disorder.

3Primary is the most severe, the longest standing by history, or the one that runs in the patient's family.

4In certain cases (based on history), major depression and substance abuse may require simultaneous treatment.

When panic disorder and major depression co-occur, the rationale for determining which disorder is to be the initial target of treatment rests on the following.

| Contents | Previous | Next |