| Contents | Previous | Next |

Guideline: Medications have been shown to be effective in all forms of major depressive disorder. Barring contraindications to these agents, antidepressant medications are first-line treatments for major depressive disorder when:

Absence of these indicators does not predict medication failure. However, when these indications are present, there is high likelihood of a beneficial response to medication. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

Individual patient considerations for acute phase medication are summarized in Table 3. The rationale for these recommendations is as follows:

For virtually all patients, the practitioner who provides the medication also provides support, advice, reassurance, and hope, as well as monitoring side-effects (including monitoring of vital signs), adjusting the dosage, or switching the medication, if needed. This “clinical management” is critical with depressed patients, whose pessimism, low motivation, low energy, and sense of social isolation or guilt may lead them to give up, not adhere to treatment, or drop out of treatment. Clinical management of medication has been detailed in the form of a manual (Fawcett, Scheftner, Clarket al., 1987) and may well be effective, either alone or with a placebo, in mildly to moderately depressed outpatients with major depressive disorder. For this reason, clinical management is viewed not only as a method to optimize dosage and patient adherence to medication, but also as a treatment, albeit nonspecific, in its own right. Common sense and a body of studies on adherence suggest that appropriate clinical management improves adherence and, therefore, patient response. In addition to routine clinical management, specific sessions aimed at increasing adherence (adherence counseling) may be indicated in the situations noted in Chapter 2.

Table 3. Considerations for acute phase medication

| Indicatiion | Strength of Indication |

| Melancholic symptoms | Very strongly recommended |

| Psychotic symptoms | Very strongly recommended |

| Severe symptoms | Very strongly recommended |

| Moderate symptoms | Strongly recommended |

| Maintenance treatment planned | Very strongly recommended |

| Previous positive reponse to medications | Strongly recommended |

| Recurrent (>three episodes) | Very strongly recommended |

| Atleast two episodes with: | |

| Poor interepisode recovery | Strongly recommended1 |

| Family history of depression | Strongly recommended1 |

| Atypical symptoms | Recommended2 |

1Beacuse a recurrent form of depression is likely (and therefore, the need for maintenance medication).

2Because there are several randomized controlled trials indicating medicatio nis more effective than placebo, but psychotherapy has not been studied to date by such a trial in this group.

The search for randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of medication treatment for adult and geriatric patients with major depressive disorder was restricted to English language literature published from 1975 to the present, as the diagnostic taxonomies in use before that time are incompatible with the present system. However, studies of MAOIs carried out between 1960 and 1975 were included because they represent an important body of work and used sufficiently well defined patient groups to make inferences to the present system. The vast majority of studies were conducted on outpatients with moderate to severe, nonpsychotic major depressive disorder seen in non-primary care settings.

Table 4 shows the number of randomized controlled trials for each medication in adult and geriatric patients with major depressive disorder. The largest number of randomized controlled trials is found for acute phase treatment. Studies of anxiolytic medications are included because these drugs are sometimes used for patients with milder forms of depression, for patients with both anxiety and depressive symptoms, and for depressed patients with complex associated medical conditions that make standard antidepressants risky to use. (Only acute phase studies were available for anxiolytic medications.) Unstudied treatments are, by definition, neither effective nor ineffective.

Intent-to-treat meta-analyses for acute phase treatment indicate that, in general, most antidepressant medications have comparable efficacy (Table 5). The drug-placebo comparisons are relatively equivalent across medications. Most reports focus on those with adequate treatment exposure (3 to 4 weeks of medication), an experimental condition that favors a higher response rate (65 to 70 percent) than that found with an intent-totreat sample (50 percent), because patients unable to take medication because of the side effects or who decide to discontinue treatment often do so early in the course of treatment. In general, the percentage of responders expected for each drug (drug efficacy) for outpatients is larger than that for inpatients—a finding that appears to result from a greater placebo response in outpatients. The drug-placebo differences often appear larger for inpatients than for outpatients, which may result from both lower attrition and lower placebo response rates for inpatients.

Other highlights of Table 5 include the following:

Over 30 randomized controlled trials of antianxiety agents used for patients with depression were found to fulfill the panel’s inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Of these, 22 investigated alprazolam; 11, diazepam; and 4, chlordiazepoxide. Two additional studies of the non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic, buspirone, were also found. Diazepam, alprazolam, and chlordiazepoxide are not FDA-approved as antidepressant medications, although they are occasionally used in patients whose general medical conditions represent a special risk for the use of FDA-approved antidepressant medications.

Most of the 22 studies with alprazolam showed it to be more effective than a placebo or as effective as an established TCA. However, 3 studies in the more severely depressed patients failed to support this finding. Half of the studies examining diazepam alone showed it to be worse than another active standard antidepressant or no better than a placebo. Of the 4 studies reporting on antidepressant effects of chlordiazepoxide, 2 showed it to be superior to a placebo or equivalent to an antidepressant, while 2 did not. Table 5 shows that by meta-analysis of the drug-placebo differences, the anxiolytics differ in their comparative antidepressant efficacy.

A few studies that were not included in the evidence table merit comment. Several studies performed about 20 years ago using the combination of chlordiazepoxide and amitriptyline (Limbitrol, an FDAapproved antidepressant) suggested a faster onset of action, but no greater oveMII efficacy than amitriptyline alone (Feighner, Brauzer, Gelenberg, et al., 1979; Rickels, Gordon, Jenkins, et al., 1970). These studies were suggestive, but generally did not use sufficiently rigorous methodology or sufficiently high medication dosages to be clearly interpretable.

Two recent studies, however, have addressed the issue of combining an anxiolytic and an antidepressant (Feet, Larsen, and Robak, 1985; Kravitz, Fogg, Fawcett, et al., 1990.) A double-blind comparison of imipramine and the combination of imipramine plus 10 mg of diazepam per day in outpatients with nonagitated depression did not demonstrate any benefit from the addition of diazepam to imipramine (Feet, Larsen, and Robak, 1985). One study found that the combination of desipramine and alprazolam was associated with a more rapid response than was desipramine alone (Kravitz, Fogg, Fawcett, et al., 1990). In fact, this study, as well as several studies of alprazolam alone in the treatment of depressed outpatients, suggests that most of the clinical benefit derived in depressed patients who respond at all to alprazolam occurs during the initial 7 to 14 days of treatment (Overall, Biggs, Jacobs, et al. 1987; Rush, Erman, Schlesser, et al., 1985). Whether this finding applies to other benzodiazepines is unstudied.

In summary, these data suggest that benzodiazepines, with the exception of the triazolo-benzodiazepine, alprazolam, should generally not be used to treat major depressive disorder, even in combination with other antidepressants. Moreover, alprazolam is not recommended for routine clinical use because no continuation or maintenance phase trials have been published and because problems associated with discontinuing this compound in remitted, depressed patients have not been fully studied. However, the presence of certain concurrent general medical conditions for which standard antidepressants are contraindicated may necessitate consideration of this agent in selected patients because of its cardiovascular safety, quick onset of action, and generally low side-effect profile.

Table 4. Number of randomized controlled trials of medication in patients with major depressive disorder 1, 2

| Medication | Adult | Geriatric | ||||

| Acute | Cont | Maint | Acute | Cont | Maint | |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | 101 [45] | 3 [2] | 3 | 8 [3] | 0 | 0 |

| Desipramine | 22 [7] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Doxepin | 19 [7] | 0 | 0 | 8 [4] | (1) | 0 |

| Imipramine | 115 [66] | (5) | 2 | 11 [7] | (1) | 0 |

| Nortriptyline | 6 [5] | 0 | 0 | 5 [2] | (1) | 1 |

| Protriptyline | 1 [0] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trimipramine | 12 [5] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heterocyclic Antidepressants | ||||||

| Amoxapine | 19 [11] | 0 | 0 | 1 [0] | 0 | 0 |

| Bupropion | 16 [10] | (4) | 0 | 2 [0] | 0 | 0 |

| Maprotiline | 28 [14] | (1) | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Trazodone | 25 [13] | (3) | 0 | 4 [3] | 0 | 0 |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||||||

| Fuoxetine | 32 [28] | (4) | 1 | 3 [2] | (1) | 0 |

| Fluvoxamine3 | 18 [12] | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Paroxetine | 10 [5] | 0 | 14 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Sertraline | 2 [2] | 0 | 14 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Manoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) | ||||||

| Isocarboxazid | 14 [9] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenelzine | 30 [20] | (2) | 1 | 1 [1] | (1) | 1 |

| Tranylcypromine | 11 [6] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anxiolytics | ||||||

| Alprazolam5 | 22 [9] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Buspirone5 | 2 [2] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlordiazepoxide5 | 4 [2] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diazepam5 | 11 [2] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

1Numbers in brackets show the number of cells that were meta-analyzed for each drug.

2Numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of double-minded, nonrandomized, extension trials within continuation or maintenance phases.

3Not FDA-approved for use in the United States.

4Completed after 1990.

5Not FDA-approved as an antidepressant medication.

Note: Cont = Continuation. Maint = Maintenance.

Table 5. Meta-analyses of antidepressant medications for patients with major depressive disorder (intent-to-treat samples)

| Medication | Adult | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Tricyclics | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | 54.0% | 60.1% | 31.3% | 21.8% | 1.3% | -0.2% |

| (12.7) | (14.1) | (15.5) | (5.7) | (11.3) | (4.2) | |

| [13] | [32] | [2] | [9] | [11] | [32] | |

| Desipramine | 47.5% | 52.1% | N/A | 33.5% | -26.0% | -7.3% |

| (10.7) | (7.7) | & | (19.5) | (15.1) | (15.4) | |

| [1] | [6] | [2] | [1] | [2] | ||

| Doxepin | 37.5% | 54.2% | N/A | 28.9% | -25.0% | 0.1% |

| (13.4) | (11.6) | (5.7) | (19.0) | (6.1) | ||

| [1] | [6] | [1] | [1] | [7] | ||

| Imipramine | 45.4% | 47.7% | 21.3% | 18.0% | -0.0% | -3.0% |

| (10.7) | (9.0) | (10.8) | (6.9) | (10.3) | (7.2) | |

| [13] | [53] | [6] | [33] | [13] | [48] | |

| Nortriptyline | 50.6% | 44.5% | N/A | 8.6% | -1.6% | 1.5% |

| (19.4) | (9.9) | (8.6) | (21.4) | (11.6) | ||

| [3] | [2] | [1] | [4] | [2] | ||

| Protriptyline | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Trimipramine | 9.6% | 63.2% | N/A | N/A | 20.1% | 0.3% |

| (12.9) | (17.2) | (17.8) | (13.6) | |||

| [2] | [3] | [2] | [1] | |||

| Total | 50.0% | 51.5% | 25.1% | 21.3% | -4.0% | -0.8% |

| (6.5) | (5.2) | (15.5) | (5.7) | (11.3) | (4.2) | |

| [33] | [102] | [8] | [46] | [32] | [92] | |

| Heterocyclics | ||||||

| Amoxapine | 54.8% | 58.9% | N/A | 27.5% | 4.3% | -1.4% |

| (14.2) | (11.6) | (9.5) | (14.9) | (6.9) | ||

| [3] | [8] | [1] | [3] | [8] | ||

| Bupropion | 51.9% | 66.6% | 39.5% | 16.8% | N/A | -5.0% |

| (9.7) | (15.3) | (10.2) | (6.6) | (7.3) | ||

| [4] | [6] | [3] | [1] | [5] | ||

| Maprotiline | 62.8% | 63.2% | N/A | -5.9% | 19.2% | 4.7% |

| (12.5) | (6.0) | (29.1) | (19.9) | (5.3) | ||

| [2] | [12] | [2] | [2] | [12] | ||

| Trazodone | 60.2% | 59.8% | 38.0% | 23.6% | 7.3% | 7.9% |

| (11.8) | (10.0) | (13.5) | (16.9) | (19.4) | (10.4) | |

| [4] | [9] | [4] | [33] | [4] | [9] | |

| Total | 55.1% | 62.3% | 39.3% | 16.5% | 8.7% | 2.1% |

| (4.8) | (11.0) | (8.3) | (9.9) | (9.7) | (4.5) | |

| [13] | [35] | [7] | [7] | [9] | [34] | |

| Medication | Geriatric | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Tricyclics | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | N/A | 44.3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.4% |

| (11.3) | (10.9) | |||||

| [3] | [3] | |||||

| Desipramine | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Doxepin | 80.0% | 31.7% | 46.7% | 26.7% | -10.0% | -7.9% |

| (12.1) | (10.0) | (19.2) | (16.0) | (15.1) | (8.3) | |

| [2] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [3] | |

| Imipramine | 94.4% | 40.7% | 63.2% | 17.4% | 11.1% | -10.7% |

| (7.2) | (9.2) | (17.1) | (15.4) | (13.8) | (15.3) | |

| [1] | [6] | [1] | [5] | [1] | [4] | |

| Nortriptyline | N/A | 50.2% | N/A | 37.5% | N/A | 0.9% |

| (16.6) | 18.7) | (13.8) | ||||

| [2] | [2] | [1] | ||||

| Protriptyline | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Trimipramine | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 83.2% | 40.4% | 53.5% | 22.0% | 1.0% | -3.9% |

| (14.3) | (6.7) | (21.9) | (14.0) | 20.7) | (6.8) | |

| [2] | [14] | [2] | [6] | [2] | [11] | |

| Heterocyclics | ||||||

| Amoxapine | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bupropion | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Maprotiline | N/A | 58.0% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25.3% |

| N/A | (9.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | (13.2) | |

| N/A | [1] | N/A | N/A | N/A | [1] | |

| Trazodone | 13.3% | 36.7% | N/A | 19.9% | -42.9% | 10.9% |

| (8.5) | (8.8) | N/A | (13.1) | (14.7) | (10.6) | |

| [1] | [2] | N/A | [1] | [1] | [3] | |

| Total | 13.3% | 43.3% | N/A | 19.9% | -42.9% | 13.4% |

| (8.5) | (12.1) | (13.1) | (14.7) | (11.8) | ||

| [1] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [4] | ||

| Medication | Adult | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||||||

| Fluxoetine | 67.2% | 46.6% | N/A | 21.7% | 0.0% | 2.7% |

| (8.2) | (11.7) | N/A | (9.7) | (11.6) | (9.2) | |

| [1] | [27] | N/A | [16] | [1] | [14] | |

| Fluvoxamine | 51.3% | 42.5% | 36.9% | 14.0% | 4.4% | -1.5% |

| (12.1) | (14.1) | (13.6) | (7.4) | (11.2) | (5.6) | |

| [6] | [6] | [1] | [4] | [6] | [6] | |

| Paroxetine | N/A | 59.2% | N/A | 21.3% | N/A | 8.0% |

| (23.1) | (23.6) | (11.9) | ||||

| [5] | [2] | [5] | ||||

| Sertraline | 55.9% | 51.7% | 14.2% | 18.9% | -27.5% | -6.0% |

| (11.7) | (4.1) | (16.3) | (5.6) | (15.0) | (5.7) | |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | |

| Total | 54.0% | 47.4% | 25.5% | 20.1% | 0.5% | 1.7% |

| (10.1) | (12.5) | (21.7) | (7.8) | (10.4) | (6.8) | |

| [8] | [39] | [2] | [23] | [8] | [26] | |

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) | ||||||

| Isocarboxazid | 56.7% | 60.1% | 15.3% | 41.3% | -14.1% | 1.9% |

| (10.5) | (7.1) | (12.6) | (18.0) | (27.5) | (10.0) | |

| [4] | [5] | [4] | [3] | [2] | [2] | |

| Phenelzine | 49.5% | 57.8% | 22.3% | 29.5% | -24.1% | 7.2% |

| (14.0) | (7.4) | (30.7) | (14.6) | (16.6) | (9.0) | |

| [7] | [13] | [5] | [7] | [6] | [11] | |

| Tranylcypromine | 58.6% | 52.8% | N/A | 21.1% | 33.3% | 10.1% |

| (10.8) | (13.4) | (25.4) | (23.5) | (23.6) | ||

| [3] | [3] | [3] | [3] | [2] | ||

| Total | 52.7% | 57.4% | 18.4% | 30.9% | -3.1% | 6.2% |

| (9.7) | (5.5 | (22.6) | (17.1) | (26.1) | (7.4) | |

| [14] | [21] | [9] | [13] | [11] | [15] | |

| Medication | Geriatric | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||||||

| Fluxoetine | 56.7% | 48.7% | N/A | N/A | 46.0% | 0.6% |

| (12.4) | (5.6) | (14.7) | (7.9) | |||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | |||

| Fluvoxamine | N/A | 57.4% | N/A | 34.0% | N/A | 19.0% |

| (8.4) | (13.5) | (12.1) | ||||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||

| Paroxetine | N/A | 64.6% | N/A | N/A | N/A | -6.6% |

| (7.4) | (10.2) | |||||

| [1] | [1] | |||||

| Sertraline | N/A | 52.2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.2% |

| 3.9 | (6.8) | |||||

| [1] | [1] | |||||

| Total | 56.7% | 54.2% | N/A | 34.% | 46.0% | 2.4% |

| (12.4)% | (6.7) | (13.5)% | (14.7) | (8.4) | ||

| [1] | [4] | [1] | [1] | [4] | ||

| Monoamine OxidaseInhibitors (MAOIs) | ||||||

| Isocarboxazid | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Phenelzine | N/A | 57.7% | N/A | 50.4% | N/A | 0.9% |

| (9.5) | (10.3) | (13.1) | ||||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||

| Tranylcypromine | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total | N/A | 57.4% | N/A | 50.4% | 0.9% | |

| (9.5) | (10.3) | (13.1) | ||||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||

| Medication | Adult | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Anxiolytics | ||||||

| Alprazolam | -5.0% | 56.6% | N/A | 27.2% | N/A | 2.6% |

| (13.1) | (9.0) | (6.1) | (6.2) | |||

| [1] | [10] | [6] | [12] | |||

| Buspirone | N/A | 59.7% | N/A | 21.4% | N/A | N/A |

| (5.2) | (14.1) | |||||

| [2] | [2] | |||||

| Chlordiazepoxide | N/A | N/A | N/A | 11.7% | N/A | -1.6% |

| (28.2) | (16.3) | |||||

| [2] | [2] | |||||

| Diazepam | N/A | 15.3% | N/A | 4.3% | N/A | -9.3% |

| (5.1) | (8.3) | (14.4) | ||||

| [1] | [1] | [4] | ||||

| Total | -5.0% | 54.3% | N/A | 20.8% | N/A | -0.4% |

| (13.1) | (8.4) | (4.0) | (7.1) | |||

| [1] | [16] | [11] | [18] | |||

| Medication | Geriatric | |||||

| Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug | ||||

| Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | Inpt | Outpt | |

| Anxiolytics | ||||||

| Alprazolam | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Buspirone | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chlordiazepoxide | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Diazepam | N/A | 15.3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | -17.6% |

| (5.1) | (9.7) | |||||

| [1] | [2] | |||||

| Total | N/A | 15.3% | N/A | N/A | N/A | -17.6% |

| (5.1) | (9.7) | |||||

| [1] | [2] | |||||

Note: the percent shown in the Drug Efficacy column is the anticipated percentage of the patients provided the treatment shown who will respond. The Drug-Placebo column shows the expected percentage difference in drug versus placebo in patients, based on direct drug-placebo comparisions in trials that included atleast these two cells. The Drug-Drug column shows the percentage difference between the named compound and all other listed antidepressant medications studied in randomized controlled trials that included at least these two cells. A negative (-) sign before the percentage means the named compound fared less well than did the "other" to which it was compared. The numbers in parenthesis are the standard deviations of the estimated percentage responders. The bracketed numbers are the number of studies on which these estimates are calculated. However, the Drug Efficacy calculations include all cells in all studies for which meta-analysis was feasible (i.e., if a study had two cells of the drug at two different dosages, efficacy trials included both cells). For drug-placebo comparisions, only those trials that contained both of these cells and reported outcome in a manner that allowed for an estimate of the percentage of randomized patients who responded were included. N/A means no information that allowed for this type of meta-analysis was available. Inpt = Inpatient. Outpt = Outpatient.

To compare acute phase medication efficacy for major depressive disorder in psychiatric versus primary care settings, the panel identified 24 randomized controlled trials conducted in primary care settings (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). It was possible to meta-analyze 13 cells (3 placebo and 10 medication) in 7 of the 24 studies (Table 6). (These primary care settings were included within the outpatient studies in Table 4 and, where possible, in the outpatient meta-analysis in Table 5.) The overall drug efficacy in the 10 medication cells was 57.8 percent, and the placebo response rate (3 studies) was 35.6 percent. The efficacy data for various antidepressant medications (and placebo) found in psychiatric settings generally apply to primary care patients with major depressive disorder, though the placebo response rate may be slightly higher in primary care settings (Rickets and Case, 1982; Rickets, Chung, Csanalosi, et al., 1987). (While some studies suggest that, for severely depressed inpatients, the standard TCAs may exceed the efficacy of the newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], meta-analyses [see Table 5] did not reveal meaningful differences in efficacy between SSRIs and TCAs in inpatient or outpatient populations.)

Table 6. Meta-analyses of primary care antidepressant medications trials

| Drug | Drug Efficacy | Drug-Placebo | Drug-Drug |

| Tricyclics | |||

| Mindham (1977) (amitriptyline) | 66.2% | N/A | |

| (verses maprotiline) | (7.7) | ||

| Rickels and Case (1982) (amitriptyline) | 52.9% | 25.7% | |

| (verses trazodone) | (6.0) | (7.9) | |

| Rickels, Chung, Csanalosi, | 45.0% | 3.7% | |

| ;et al. (1987) (imipramine) | (6.8) | (9.9) | |

| (verses alprazolam) | 62.5% | N/A | |

| Winsauer and O'Hair (1984) (doxepin) | 76.6% | N/A | 13.7% |

| (verses amoxapine) | |||

| Total | 55.5% | 15.0% | 1.5% |

| (8.2) | (19.0) | (9.3) | |

| [4] | [2] | [4] | |

| Heterocyclics | |||

| Mindham (1977) (maprotiline) | 52.7% | N/A | -13.5% |

| (versus amitriptyline) | (8.1) | (11.2) | |

| Moon and Davey (1988) (trazodone) | 90.5% | N/A | -0.4% |

| (verses mianserin) | (6.3) | (8.6) | |

| Richards, Midha, and Miller | 60.0% | N/A | 24.6% |

| (1982) (trazodone) | (7.2) | (11.7) | |

| (verses mianserin, diazepam) | |||

| Rickels and Case (1982) (trazodone) | 50.0% | 20.9% | -2.8% |

| (verses amitriptyline) | (6.0) | (8.0) | (8.4) |

| Winsauer and O'Hair (1984) | 76.6% | N/A | 13.7% |

| (amoxapine) (verses doxepin) | (7.4) | (11.3) | |

| Total | 62.8% | 22.9% | 7.0% |

| (13.9) | (8.0) | (11.8) | |

| [5] | [1] | [6] | |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors | |||

| Corne and Hall (1989) (fluoxetine) | 52.7% | N/A | -13.5% |

| (verses dothiepin) | (8.1) | (11.2) | |

| Grand Total | 57.8% | 18.2% | 2.2% |

| (8.9) | (12.1) | (8.5) | |

| [10] | [3] | [11] |

1Two cells.

Note: The numbers in parenthesis are the standard deviations of the estimated percentage of responders. The bracketed numbers are the numbers of studies on which these esimates are calculated.

Guideline: No one antidepressant medication is clearly more effective than another. No single medication results in remission for all patients. The selection of a particular medication for a particular patient depends on a variety of factors: short-term and long-term side effects (Strength of Evidence = A); prior positive/negative response to the medication (Strength of Evidence = A); history of first-degree relatives responding to a medication (Strength of Evidence = B); concurrent, nonpsychiatric medical illnesses that may make selected medications more or less risky or noxious (Strength of Evidence = A); the concomitant use of other nonpsychotropic medications that may alter the metabolism or increase the side effects of the antidepressant medication (Strength of Evidence = A); likelihood of adherence based on patient’s history (Strength of Evidence = B); type of depression (Strength of Evidence = B); effectiveness when given once a day (Strength of Evidence = B); degree of interference in life style expected from treatment (Strength of Evidence = B); cost of the medication; the practitioner’s experience with the agent (Strength of Evidence = C); patient preference (Strength of Evidence = C); and other considerations. While these factors may point toward one or another medication, none is sufficiently predictive to allow selection for treatment with certainty. Therefore, an empirical trial and careful evaluation of outcome, with subsequent revision if response is insufficient, is recommended.

Side effects occur in a selected number of patients taking any medication and are typically dependent on dosage and blood level. Many side effects are more likely to occur at the initiation of treatment or within a short time following dosage increases, and patients often adapt to side effects over time. The reader is urged to review current publications for data on the actual incidence of various specific side effects of each medication (AMA, 1990; Physician's Desk Reference, 1992; USP, 1992)

A drug’s short- and long-term side effects are critical factors to consider in treatment selection. In general, of the tricyclics, the secondary amines (e.g., desipramine, nortriptyline) have equal efficacy, but fewer side effects than do the parent tertiary amines (e.g., imipramine, amitriptyline) (Table 7). The secondary amines are especially preferred in the elderly, in whom the anticholinergic side effects of the tertiary amines may reduce adherence or be particularly severe. If the patient is a candidate for maintenance therapy, the long-term side effects are key considerations in maximizing adherence, and they should be minimal. The newer antidepressants (e.g., bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, trazodone) are associated with fewer long-term side effects, such as weight gain, than are the older tricyclic medications. The presence of certain nonpsychiatric medical conditions may favor some agents over others because of their side-effect profiles. For example, for patients with coronary artery disease, drugs that do not lower blood pressure or are associated with no cardiac conduction changes (e.g., bupropion, fluoxetine) may be preferable.

Table 7. Side-effect profiles of antidepressant medications

| Drug | Side Effect1 | ||||||

| Anti-cholinergic2 | Central Nervous System | Cardiovascular | Other | ||||

| Drowsiness | Insomnia/Agitation | Orthostalic Hypo-tension | Cardiac Arrhy-thmia | Gastro-intestinal Distress | Weight Gain (Over 6 kg) | ||

| Amitriptyline | 4+ | 4+ | 0 | 4+ | 3+ | 0 | 4+ |

| Desipramine | 1+ | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 1+ |

| Doxepin | 3+ | 4+ | 0 | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 3+ |

| Imipramine | 3+ | 3+ | 1+ | 4+ | 3+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Nortriptyline | 1+ | 1+ | 0 | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 1+ |

| Protriptyline | 2+ | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 0 |

| Trimipramine | 1+ | 4+ | 0 | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 3+ |

| Amoxapine | 2+ | 2+ | 2+ | 2+ | 3+ | 0 | 1+ |

| Maprotiline | 2+ | 4+ | 0 | 0 | 1+ | 0 | 2+ |

| Trazodone | 0 | 4+ | 0 | 1+ | 1+ | 1+ | 1+ |

| Bupropion | 0 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 1+ | 1+ | 0 |

| Fuoxetine | 0 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 3+ | 0 |

| Paroxetine | 0 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 3+ | 0 |

| Sertraline | 0 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 3+ | 0 |

| Manoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | 1 | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ | 0 | 1+ | 2+ |

10 = absent or rare

1+

2+ = in between

3+

4+ = relatively common

2Dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary hesitancy, constipation

Guideline: If the patient has a concurrent, non-mood psychiatric disorder, then medications that are effective in both depression and the associated psychiatric condition are preferred. (Strength of Evidence = B.)

If a patient suffers concurrently from both major depressive and obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example, the practitioner may be well advised to choose a medication, such as clomipramine or fluoxetine, that has demonstrated efficacy for both conditions.

Specific symptom clusters may suggest the appropriateness of a particular drug class for treatment. For example, patients whose conditions have atypical features appear to fare better on MAOIs (Liebowitz, Quitkin, Stewart, et al., 1988; Quitkin, Harrison, Stewart, et al., 1991; Quitkin, McGrath, Stewart, et al., 1990; Quitkin, Stewart, McGrath, et al., 1988; Thase, Carpenter, Kupfer, et al., 1991) or SSRIs (Reimherr, Wood, Byerley, et al., 1984) than on standard TCAs. Similarly, given the available data, the presence of psychotic features points more strongly toward TCAs combined with neuroleptics (three open trials or retrospective analyses [Charney and Nelson, 1981; Frances, Brown, Kocsis, et al., 1981; Minter and Mandel, 1979b] and five prospective randomized controlled trials [Kaskey, Nasr, and Meltzer, 1980; Minter and Mandel, 1979a,b; Moradi, Muniz, and Belar, 1979; Nelson and Bowers, 1978; Spiker, Weiss, Dealy, et al., 1985]), ECT (Avery and Lubrano, 1979; Avery and Winokur, 1977; Brown, Frances, Kocsis, et al., 1982; Charney and Nelson, 1981; Davidson, McLeod, Kurland, et al., 1977; DeCarolis, Gilberti, Roccatagliata, et al., 1964; Frances, Brown, Kocsis, et al., 1981; Glassman, Kantor, and Shostak, 1975; Lykouras, Malliaras, Christodoulou, et al., 1986a,b; Minter and Mandel, 1979a,b; Moradi, Muniz, and Belar, 1979), or possibly, based on one study, amoxapine (Anton and Burch, 1990; Anton and Sexauer, 1983).

If the patient is considered likely to take an overdose, the practitioner is advised to dispense only 1 week’s supply of potentially lethal antidepressants (e.g., the tricyclics or MAOIs), to see the patient at least weekly, and to be readily available by telephone. In such situations, certain heterocyclic agents (bupropion or trazodone) or SSRIs, which appear safer in cases of potential overdose, may be preferred.

The likelihood that it will be necessary to monitor therapeutic blood levels of the drug is also a consideration in the selection of an antidepressant. In a patient who is older, who has other medical conditions, or who is taking medications that affect the metabolism of antidepressants, determining the blood level of the medication to gauge the minimal therapeutic dosage for that patient may be particularly helpful. Similarly, patients with complex general medical conditions that put them at particular risk for side effects from standard antidepressant medications may need blood level monitoring to ensure that the lowest possible dosage is used. Thus, an antidepressant with better established therapeutic and toxic levels, such as nortriptyline, may be preferred over another for which such levels are less well studied.

Guideline: If the patient previously failed to respond to an adequate trial of or could not tolerate the side effects of a particular compound, that agent is generally avoided. Similarly, if the patient has previously responded well to and has had minimal side effects with a particular drug, that agent is to be preferred. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

There is evidence, although not randomized controlled trials, that response to different classes of medication may run in families. (For a review, see Stern, Rush, and Mendels,1980.) Thus, if the patient has a first-degree relative who responded well to a compound, a drug from the same class may be preferred. Whether this suggestion applies to the newer compounds, such as the SSRIs, has not been studied.

A history of failure to respond to a truly adequate trial of a drug in one class, such as the TCAs, strongly suggests that it would be appropriate to try a medication from a different class rather than another drug from the same class. The evidence for this recommendation is strongest for switching patients who have failed to respond to a TCA or an MAOI. Evidence is suggestive for switches among other classes of antidepressant medications (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming).

If the medication is ineffective or not tolerated, then the dosage can be adjusted or the medication changed. In milder cases, medication may be stopped and a trial of time-limited psychotherapy substituted. For patients with partial responses to medication, the dosage is adjusted or the blood level monitored to ensure that it is adequate. In some patients, adjunctive psychotherapy may be indicated, depending on the medication type. In others, a switch to another medication is logical. In yet others, adjunctive medication (augmentation) with agents such as lithium may be preferable.

Table 8 provides an overview of the pharmacology of the various antidepressants, the usual therapeutic dosages, half-lives, and potentially fatal drug interactions. The suggested therapeutic blood levels for various antidepressant medications are as follows:

Well Established Therapeutic Ranges

Therapeutic ranges have generally not been established by randomized controlled trials with patients on predesigned fixed medication levels in which group efficacy was measured. Rather, the suggested ranges are derived from laboratory/clinical interaction such that most patients who responded did so with dosages that produced the therapeutic levels indicated. Furthermore, most of these levels were established on inpatients. Their applicability to primary care outpatients is largely unstudied.

Table 8. Pharmacology of antidepressant medications

| Drug | Therapeutic Dosage Range (mg/day) | Average Range of Elimination Half-Lives (Hours)1 | Potentially Fatal Drug Interactions | |

| Tricyclics | ||||

| Amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep) | 75-300 | 24 | (16-46) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Clomipramine (Anafranil) | 75-300 | 24 | (20-40) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Desipramine (Norpramin, Pertofrane) | 75-300 | 18 | (12-50) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Doxepin (Adapin, Sinequan) | 75-300 | 17 | (10-47) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Imipramine (Janimine, Tofranil) | 75-300 | 22 | (12-34) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) | 40-200 | 26 | (18-88) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Protriptyline (Vivactil) | 20-60 | 76 | (54-124) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Trimipramine (Surmontil) | 75-300 | 12 | (8-30) | Antiarrhythmics, MAOIs |

| Heterocyclics | ||||

| Amoxapine (Asendin) | 100-600 | 10 | (8-14) | MAOIs |

| Bupropion (Wellbutrin) | 225-450 | 14 | (8-24) | MAOIs (possibly) |

| Maprotiline (Ludiomil) | 100-225 | 43 | (27-58) | MAOIs |

| Trazodone (Desyrel) | 150-600 | 8 | (4-14) | --- |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | ||||

| Fuoxetine (Prozac) | 10-40 | 168 | (72-360)2 | MAOIs |

| Paroxetine (Paxil) | 20- 50 | 24 | (3-65) | MAOIs3 |

| Sertraline (Zoloft) | 50-150 | 24 | (10-30) | MAOIs3 |

| Manoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)4 | For all 3 MAOIs:Vasoconstrictors,5decongestants,5meperidine, and possibly other narcotics | |||

| Isocarboxazid (Marplan) | 30- 50 | Unknown | ||

| Phenelzine (Nardil) | 45- 90 | 2 | (1.5-4.0) | |

| Tranylcypromine (Parnate) | 20- 60 | 2 | (1.5-3.0) | |

1Half-lives are affected by age, sex, race, concurrent medications, and length of drug exposure.

2Includes both fluoxetine and norfluoxetine.

3Includes both fluoxetine and norfluoxetine.By extrapolation from fluoxetine data.

4MAO inhibition lasts longer (7 days) than drug half-life.

5Including pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, phenylpropanolamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and others.

Nortriptyline has the best defined therapeutic window (upper and lower limits). The lower limits for the remaining medications are reasonably well established; upper limits are far less well established. The routine use of therapeutic blood level determinations generally is not needed, although their selected use in particular clinical instances can be of value.

Table 9 suggests options for first- and second-line treatments. Because there is no strong evidence for differential efficacy of the various medications, selection rests on other factors. Assuming that a patient has had no prior treatment, that the depression is of moderate or greater severity and not associated with psychotic symptoms, and that the patient has no other associated general medical disorders, side effects become a significant consideration. The secondary amines are listed as first- and second-line choices because they have fewer side effects than do the tertiary amine tricyclics (as do the newer heterocyclics). The available MAOIs require significant dietary restrictions and are, therefore, alternatives. Anxiolytics, particularly alprazolam, have some evidence for efficacy, but have substantial disadvantages. Therefore, alprazolam is an option only in very selected situations.

Table 9. Selecting among antidepressant medications for depressed outpatients

|

1Other first- and second-line choices are recommended for patients with arrhythmias, cardiac conduction defects, ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or cardiac valve disease.

2Evidence is clearest for alprazolam. Not recommended in severe depressions as studies reveal reduced efficacy. Not recommended for prolonged care as no studies longer than 12 weeks are available. Not recommended when FDA-approved antidepressant medications can be used safely. For buspirone, efficacy is suggested in those with primary anxiety disorders and mild associated depressive symptoms.

Note: Evidence for efficacy for severely depressed inpatients is more abundant for the standard tricyclics than for newer agents.

Although their efficacy is equal to that of other standard antidepressant medications, the MAOIs are usually not first-line treatments because of the required dietary restrictions and potentially fatal interactions with other medications. However, patients who have major depressive disorder with atypical features may optimally benefit from such agents. As for second-line treatments, there is substantial evidence that patients who fail to respond fully or partially to tricyclic medications may benefit substantially from MAOIs and modest evidence that these patients may benefit from the newer SSRIs.

Since providing patient support and education optimizes adherence, facilitates dosage adjustments, minimizes side effects, and allows monitoring of clinical response, careful followup is essential. The panel recommends that patients with more severe depressions be seen weekly for the first 6 to 8 weeks of acute treatment. Once the depression has resolved visits every 4 to 12 weeks are reasonable. Patients with less severe illness may be seen every 10 to 14 days for the first 6 to 8 weeks or more frequently if required to ensure adherence.

Several suggestions can be made concerning dosage adjustments for frequently prescribed medications in primary care. For TCAs, patients generally begin with a low dosage (e.g., 25 to 50 mg/day of desipramine) administered at bedtime. The dosage may be increased in increments to the full therapeutic dosage over 1 to 3 weeks. There is no pharmacologic rationale for prescribing most TCAs in divided doses since most have halflives approximating 24 hours. Once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime, often minimizes side effects. The full therapeutic dosage is maintained until the patient has either responded or clearly failed to respond. The major consideration in dosage increases is the emergence of side effects. Because side effects decrease with time, the patient should be told that they may occur, but are likely to decrease within several weeks of beginning medication.

Fluoxetine may be initiated at 20 mg/day, usually given in the morning, and should be maintained at a full therapeutic dosage (20 mg/day) for at least 4 to 8 weeks before the dosage is increased. Some patients may require less than 20 mg/day, while others may require more. Some patients feel restless or hyperalert with fluoxetine or develop initial insomnia. If significant side effects occur within 7 days, the dosage should be lowered or the medication changed, as the drug at a fixed oral dosage will continue to increase in plasma concentration for 4 weeks (until steady state is reached). Bupropion must be given in divided doses up to 450 mg/day. Dosages above 450 mg/day are associated with an increased risk of seizure.

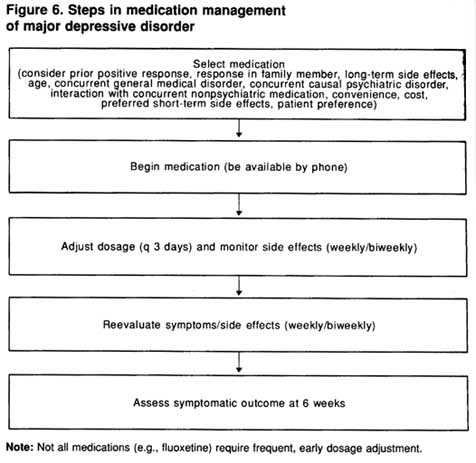

Figure 6 outlines the general steps in the medication management of depression with or without psychotherapy.

Figure 6. Steps in medication management of major depressive disorder

Not: Not all medications (e.g., fluoxetine) require frequent, early dosage adjustment.

Determinations of antidepressant drug blood levels can establish that patients are receiving a therapeutic dosage, help in the evaluation of adherence, or exclude toxicity. Logically, patients cannot be declared to be nonresponsive to a treatment unless the steady-state serum level is within the therapeutic range for at least 2 to 4 weeks. While the presence or absence of side effects can be helpful indicators of trial adequacy, serum levels are more accurate; patients differ widely in their individual sideeffect sensitivity and in the blood levels achieved with a fixed oral dosage. Blood level determinations also enable clinicians to adjust the oral medication dosage for differences in metabolism due to age, race, drug interactions, concurrent medical conditions, or erratic adherence (Amsterdam, Brunswick, and Mendels, 1980; Bourin, Kergueris, and Lapierre, 1989; Glassman, Schildkraut, Orsulak, et al., 1985; Preskorn, Dorey, and Jerkovich, 1988; Preskorn and Kent, 1984; Voris, Morin, and Kiel, 1983).

Four antidepressant medications—nortriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, and amitriptyline—have more consistent evidence of a minimal therapeutic blood levels. Most have established toxic ranges, and a few have established upper therapeutic ranges. The best established therapeutic blood levels are for nortriptyline.

Toxic blood levels can occur in patients who initially exhibit no clinical signs of tricyclic toxicity (Tamayo, Fernandez de Gatta, Gutierrez, et al., 1988). Similarities between depressive and toxic symptoms in patients with deteriorating clinical status often make it difficult for clinicians to assess a patient’s condition correctly without quantitative blood level information (Appelbaum, Russell, Orsulak, et al., 1979; Preskorn and Simpson, 1982; Preskorn, Weller, Jerkovich, et al., 1988). In addition to high antidepressant medication dosages, risk factors for developing toxic levels include advanced age and serious concurrent, general medical illnesses. For these high-risk patients, determinations of medication blood levels provide a safe, effective method of attaining an optimal dosage while avoiding toxicity.

Patients for whom blood level monitoring may be particularly helpful include the following:

These situations are most pertinent for patients taking a medication for which therapeutic levels are well established.

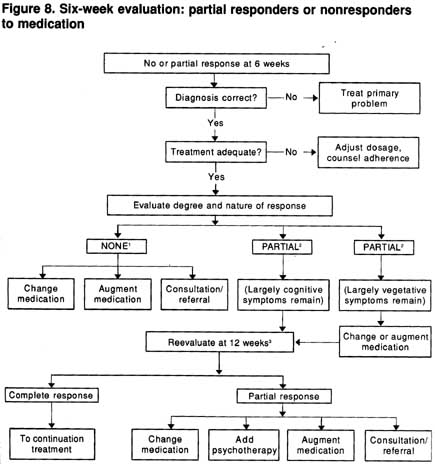

Guideline: If the patient has not responded at all or has only a minimal symptomatic response to medication by 6 weeks, two steps are needed: (1) reassessment of the adequacy of the diagnosis and (2) reassessment of the adequacy of treatment. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

Ongoing (but undisclosed) substance abuse or underlying general medical conditions causing the depression are two common diagnostic pitfalls. If either is found, treatment focuses on the relevant potential cause. In cases of substance abuse, a substance-free state for 6 to 8 weeks is usually sufficient to determine whether the depressive syndrome will remit without additional formal treatment for the depression. In some cases, however, the abusive and depressive disorders may require treatment simultaneously. Furthermore, some patients may have another psychiatric condition not initially disclosed to the practitioner, so reevaluation for both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric illnesses should be strongly considered for partial responders.

In addition to reassessment of the diagnosis, reevaluation of the adequacy of treatment is indicated. Medication underdosing is a common cause of nonresponse. Increasing dosages should be given in the first few weeks for most antidepressants. The major exception is fluoxetine, for which the starting dosage (20 mg/day) is often the full therapeutic dosage.

At 6 weeks (range, 4 to 8 weeks), if medically safe, a further dosage increase may be called for, especially in those without significant side effects. In selected clinical situations and with selected medications, a blood level determination may reveal suboptimal antidepressant levels in poor adherers, rapid metabolizers, or those concurrently taking medications that alter the metabolism of antidepressants (e.g., anticonvulsants). If the therapeutic range is well established, and the patient’s blood levels are not within that range, adjust the dosage appropriately.

Some evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests a poorer response to TCAs alone in patients with the following conditions:

While these conditions may be associated with a lower response rate to standard tricyclic medications in some studies, the response rates are still nearly always greater than those obtained with placebo. Typically, the initial strategy is to use a single standard antidepressant medication before moving to more complex regimens, even for these subgroups. The exception is for psychotic depression, where the combination of a neuroleptic and an antidepressant or ECT may be optimal initial treatments.

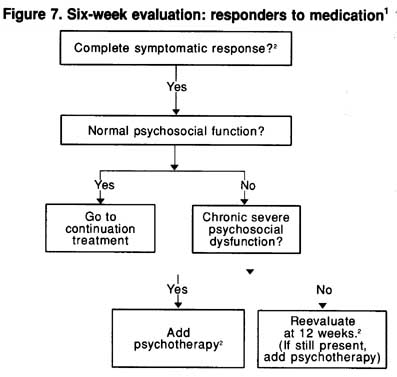

Guideline: By 6 weeks, patients will have responded fully, partially, or not at all. For those with a full symptomatic response, psychosocial function may either have returned to normal or still be impaired. For full responders, continuation phase treatment should begin with visits every 1 to 3 months. For those who still have impaired psychosocial function, many are likely to improve over the next 6 weeks. Therefore, neither the dosage nor the medication type need be changed, but the patient’s condition should be reevaluated in 6 weeks to determine whether normal function has returned. If so, continuation treatment is begun. For patients with continued impairment, psychotherapy focused on the residual psychosocial difficulties may be beneficial. (Strength al Evidence = B.)

The algorithms shown in Figures 7 and 8 for the management of patients initially treated with medication alone are based on the patients’ level of response. Depressive symptoms remit with the first medication in 40 to 60 percent of patients. These patients usually return to their previous level of psychosocial function, although sometimes weeks to months after full symptom remission. Whether or not residual psychosocial problems are present, patients should be maintained on the same dosage of medication found effective in acute phase treatment for 4 to 9 months of continuation treatment. For patients with recurrent depressive episodes, maintenance medication is an option (see Chapter 9).

If the patient continues to have psychosocial problems following a good symptomatic response to medication, psychotherapy may be added. The rationale for delaying the use of formal psychotherapies to ameliorate associated psychosocial problems rests on recent evidence that, for outpatients with major depressive disorder who respond to medication, psychotherapy, or the combination during acute treatment, return to the premorbid level of psychosocial function often occurs, but is delayed by weeks to months following significant symptomatic improvement (Mintz, Mintz, Arruda, et al., 1992).

Figure 7. Six-week evaluation: responders to medication1

1Complete response-with no or very few symptoms.

2These suggestions are based on indirectly relevant data, logical inference, and clinical experience.

Guideline: For those with no meanigful symptom responded by 6 weeks (or by 4 weeks in the severely ill), there are five possible options (Strength of Evidence = A):

Figure 8 provides a flow chart for the management of those with a partial or poor symptomatic response at 6 weeks. (As noted earlier, the symptomatic response should be assessed during the first 6 weeks as well.)

Guideline: Before changing a patient’s treatment, the practitioner is advised to evaluate the adequacy of the medication dosage. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

Figure 8. Six-week evaluation: partial responders or nonresponders to medication

1No response-patient is nearly as symptomatic as at pretreatment.

2Partial response-patient is clearly better than at pretreatment, but still has significant symptoms. Consultation or referral may be valuable before proceeding further.

3Suggestions for management are based on some indirectly relevalnt studies. logic, and clinical experience.

Medication underdosing is the most common problem in the oars responsive patient in primary care consideration should be given to either empirically raising the dosage or determining the blood level.

In addition, response to fluoxetine and other standard antidepressants at the typical “adequate” dosages may continue to improve between weeks 4 and 8 of treatment (Dornseif, Dunlop, Potvin, et al., 1989; Schwe~zer, Rickels, Amsterdam, et al., 1990). Thus, even for those with a partial response by week 6, a longer trial at the therapeutic dosage is a logical option.

Guideline: Switching to a new medication is an option after an adequate trial of the first treatment. A general medical principle is that a combination of two drugs should not be used when one drug will suffice. switching medications is often preferred over augmentation as an initial strategy. (Strength of Evidence = A.)

An adequate medication trial likely will include:

Several reports describe patients who did not respond to traditionally adequate dosages of TCAs, but who were “converted” to responders who the TCA dosage was adjusted to higher than normal dosages (Amsterdan Brunswick, and Mendels, 1979; Schuckit and Feighner, 1972; Simpson, Lee, Cuculic, et al., 1976). However, nortriptyline has been shown to ha a therapeutic window for plasma levels. Therefore, nortriptyline dosages may need to be titrated downward in nonresponders with high plasmalevels.

The tricyclic, heterocyclic, and SSRI antidepressants differ considerably in both pharmacologic actions and side effects. Therefore, i is reasonable to expect that an alternate antidepressant may prove effect) in some patients who either do not respond to or cannot tolerate adequat, dosages of a standard TCA. Three studies document tricyclic response rates of approximately 10 to 30 percent in patients with a history of nonresponse to another TCA (Beasley, Sayler, Cunningham, et al., 1990 Charney, Price, and Heninger, 1986; Reimherr, Wood, Byerley, et al.,1984).

The literature is replete with case reports of patients who failed to respond to multiple trials of standard agents, but who nevertheless responded to newer antidepressants, such as bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline. The efficacy of crossover treatment with bupropion in tricyclic nonresponders has been described in a report including both a small double-blind study of inpatients and a larger, open-label outpatient study (Stern, Harto-Truax, and Bauer, 1983). The utility of fluoxetine in patients with a history of tricyclic nonresponse h, been demonstrated in two controlled trials (Beasley, Sayler, Cunninghar et al., 1990; Reimherr, Wood, Byerley, et al., 1984). Open-label treatme with trazodone was reported to be effective in 56 percent of a diverse group of 25 TCA nonresponders (Cole, Schatzberg, Sniffin, et al., 1981

In addition, MAOIs may be effective for patients who do not respond to TCAs. Nine open-label reports provide evidence that 40 to 60 percen patients who have not responded to at least one TCA respond to an M} For example, 50 percent of highly refractory patients in one study responded to tranylcypromine (Nolen, Van De Putte, Dijken, et al., 1985, 1988). Four double-blind crossover studies of MAOI efficacy in patients who did not respond to a TCA revealed similar results (Lipper, Murphy, Slater, et al., 1979; McGrath, Stewart, Harrison, et al., 1987; Potter, Murphy, Wehr, et al., 1982; Thase, Mallinger, McKnight, et al., 1992). In an open-label crossover study, MAOI response was found to be both statistically and clinically significant (57 percent response rate) in patients who had been vigorously treated with imipramine (mean dosage: 257 mg/day) and psychotherapy (These, Frank, Mallinger, et al., 1992). These studies suggest that it would be appropriate to switch a patient who fails to respond to a TCA to an MAOI. Whether such a switch would be as strongly indicated had the patient also failed to respond to a nontricyclic agent (e.g., fluoxetine, trazodone, or bupropion) is not known.

In summary, based on these data, one may expect a 30 to 60 percent response when a tricyclic is “crossed over” to a nontricyclic. Similar data have not been presented for amoxapine, maprotiline, or alprazolam. The timing of a switch to a new medication depends on the patient’s treatment history and the length and adequacy of the current treatment. For nonresponders at 6 weeks (assuming that the trial has been at an adequate dosage and the diagnosis is correct), a switch is a reasonable option. For partial responders at weeks 8 to 12 (again assuming an adequate trial and correct diagnosis), a switch is also logical. Some clinicians believe a switch (or augmentation with another medication) is particularly advisable for patients with residual vegetative symptoms. When switching medications, the practitioner should be well informed of drug-drug interactions (fluoxetine raises the blood levels of TCAs); pharmacokinetics (shorter versus longer half lives); and untoward effects of combination medication (TCAs plus MAOIs). The specific steps in switching or augmenting depend on application of such knowledge.

Guideline: Augmentation of the initial medication with a second one i not advised until the initial trial has been adequate in time and dosag (Strength of Evidence = A.)

There is evidence from tertiary care studies that, for both partial responders and nonresponders, augmentation, particularly with lithium, c be helpful in 20 to 50 percent of patients (Depression Guideline Panel, forthcoming). Augmentation carries the additional risks of more side effects, greater expense, and potentially complex drug-drug interactions. A history of nonresponse to adequate trials of other individually prescrib antidepressants increases the likelihood that augmentation may be requird Because augmentation strategies are an evolving specialized area of knowledge requiring substantial sophistication in psychopharmacology, well as greater risk to patients, the panel recommends that, where feasible, primary care practitioners consider consultation (at a minimum) or referral before embarking on this option.

Guideline: For patients with a partial response at week 12 whose residual symptoms are largely psychological rather than vegetative, psychotherapy may be added and the medication remain unchanged. If the residual symptoms at 6 or 12 weeks are largely somatic or vegetative, either adjunctive medication or a new, different medication may be indicated. (Strength of Evidence = C.)

Both of these options are based on clinical experience, logic, and panel consensus. They have not been impirically tested.

Guideline: In any case in which the practitioner feels that he or she lacks sufficient knowledge and/or experience to manage a patient's medication or if two or more attemps at acute phase medication treatment have failed or resulted in only partial response, the practitioner is advised to seek a consultation from or refer the patient to psychiatrist well trained in psychopharmacology. In addition, if drug-drug interactions are anticipated (for example, in patients taking nonpsychotropic medications that may interact with the antidepressants), consultation from a pharmacist or psychiatrist is advisable. (Strength of Evidence = C.)

| Contents | Previous | Next |