|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and nativity: 1999 to 2100; published January 2000 |

| Contents | Previous | Post Test |

This guidebook is designed for use by providers of services to racially and ethnically diverse older populations. There is growing interest in learning how effective, culturally appropriate services can be provided by professionals who have mastered culturally sensitive attitudes, skills, and behaviors. In designing service programs, we cannot assume that methods designed for majority group older persons will automatically apply to minority elders. This poses a challenge and opportunity for all of us to design culturally appropriate interventions that are responsive to the needs of minority communities and to offer support that withstands the changing needs of diverse populations over time. Racial and ethnic minorities face many barriers in receiving adequate care. These include difficulties with language and communication, feelings of isolation, encounters with service providers lacking knowledge of the client’s culture and challenges related to the socioeconomic status of the client. Often, service providers have a responsibility to provide a voice for clients who cannot speak for, or represent, themselves.

There is consensus that social services, health promotion/disease prevention, and health services should be culturally sensitive to better meet the needs of older minority Americans. Compelling evidence indicates that race and ethnicity correlate with persistent and, often, increasing health and socioeconomic disparities among U.S. populations. Although there is progress in the overall health of the nation, there remains a continuing disparity in the burden of illness and death experienced by African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Indians and Alaska Natives, and Asian and Pacific Islanders. These disparities are believed to be the result of the complex interaction among genetic variation, environmental factors, specific health behaviors, and factors of service delivery. Health disparities, and other disparities which set racial and ethnic minority populations apart from the mainstream, are due, at least in part, to problems experienced in accessing and effectively utilizing health and human services. However, a solid and growing body of research now indicates that one of the major reasons that services remain inaccessible and underutilized is because they are not responsive to the needs of the group being served....they are not “culturally sensitive.” Additional, research is needed to better understand these relationships and to acquire new insights into eliminating the disparities and developing new ways to apply our existing knowledge to this goal. Improving access to quality services will require working with communities to identify culturally sensitive implementation strategies.

Understanding culture helps service providers avoid stereotypes and biases that can undermine their efforts. It promotes a focus on the positive characteristics of a particular group, and reflects an appreciation of cultural differences. Culture plays a complex role in the development of health and human service delivery programs.

Approaches that build on the strengths of minority communities and understand and respect minority cultures result in interventions which can lead to healthy practices and behaviors. Some call this an “emic” approach—working from the inside, using the strengths, perspectives, and strategies which elders and their families identify for themselves as being most effective. It is important for direct service providers to acknowledge the significance of culture in people’s problems as well as their solutions. Although there is some research to suggest that the optimal situation is one in which there is similarity between the service recipient and worker, such matches are a rare luxury. Consider the second–generation Vietnamese-American mental health social worker whose clients consist of Japanese-American and African-American families. It would not be feasible for the social worker to try to memorize cultural traits while trying to become familiar with these families. Subgroups and individuals within particular groups are quite diverse. Instead, the social worker must have an appreciation of the cultural differences between her culture and her clients’, respect her clients culture, and behave in a manner that exemplifies this respect. The goals in becoming more culturally competent are to continue to learn about differences and to rid oneself of stereotypes. Cultural competence demands an approach to service recipients in which assumptions are few.

Culture has been defined as “the shared values, traditions, norms, customs, arts, history, folklore, and institutions of a group of people.” Why should we even be concerned about culture? First, understanding culture helps us to understand how others interpret their environment. We know that culture shapes how people see their world and how they function within that world. Culture shapes personal and group values and attitudes, including perceptions about what works and what doesn’t work, what is helpful and what is not, what makes sense and what does not. Secondly, understanding culture helps service providers avoid stereotypes and biases that can undermine their efforts. It promotes a focus on the positive characteristics of a particular group, and reflects an appreciation of cultural differences. Finally, culture plays a complex role in the development of health and human service delivery programs.

|

Intervening Factors The cultures of patients and providers may be affected by:

Source: AMA, Culturally Competent Health Care for Adolescents, 1994 |

While we know that cultural influences shape how individuals and groups create identifiable values, norms, symbols, and ways of living that are transferred from one generation to another, it is important for us to distinguish the differences created by such factors as age, gender, geographic location, and lifestyle. Race and ethnicity are commonly thought to be dominant elements of culture, but a true definition of culture is actually much broader than this. For example, ethnic and racial groups are usually categorized very broadly as African American, Hispanic, American Indian and Native Alaskan, or Asian American and Pacific Islander. These broad categories are sometimes misleading, because they can often mask substantial differences within groups. The larger group may share nothing more than common physical traits, language, or religious backgrounds. We often fail to consider the distinct factors which influence culture within larger populations that determine how people think and behave.

|

Cultural Competence Checklist for Success The cultures of patients and providers may be affected by:

Adapted from material developed by the National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Child Development Center. |

Cultural competence is defined as “a set of cultural behaviors and attitudes integrated into the practice methods of a system, agency, or its professionals, that enables them to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.” Cultural competency is achieved by translating and integrating knowledge about individuals and groups of people into specific practices and policies applied in appropriate cultural settings. When professionals are culturally competent, they establish positive helping relationships, engage the client, and improve the quality of services they provide.

It is important to understand that the concept of cultural competency has two primary dimensions: surface structure and deep structure. Borrowed from sociology and linguistics, these terms have been used to describe similar dimensions of culture and language.

Surface structure involves matching intervention materials and messages to observable, “superficial” (though nonetheless important) characteristics of a target population. For audiovisual materials, surface structure may involve using people, places, language, music, food, and clothing familiar to and preferred by the target audience. Surface structure also includes identifying which channels (e.g., media) and settings (e.g., churches, senior centers) are most appropriate for the delivery of messages and programs.

Deep structure involves sociodemographic and racial/ethnic population differences in general as well as how ethnic, cultural, social, environmental and historical factors may influence specific behaviors. Whereas surface structure generally increases the “receptivity” or “acceptance” of messages, deep structure conveys relevance. Surface structure is a prerequisite for feasibility, while deep structure determines the efficacy or impact of a program.

A significant external barrier to health care access is lack of health care insurance and out-of-pocket health care costs. Factors that have been shown to significantly affect out-of-pocket health care costs include poor health, high levels of functional impairment, limited education, and low income. Because minority elders are in general in poorer health, suffer more functional impairments, have more limited educations and lower incomes than the general population, they may face significantly higher burdens for out-of-pocket costs. Out-of-pocket costs also account for a much higher proportion of income for lower income groups than higher income groups. The current average out-of-pocket costs amount to 19 percent of total income for all Medicare beneficiaries, but account for 28 percent of income for those in poorer health, 24 percent for those with one or more functional impairments, 21 percent for those who did not complete high school and 31.5 percent for those at the lowest income levels.

Another set of structural barriers is logistical difficulties, including a lack of transportation, language difficulties and illiteracy. Transportation difficulties disproportionately affect lower income racial and ethnic minority elders, many of whom do not have automobiles and, even more importantly, may not have the language skills and information necessary to get a driver’s license and navigate through their community. Many of these elders also experience confusion regarding public transportation and other resources available to help them access services.

Some barriers to services can be considered “internal” because they are characteristics of the minority groups, and they include styles of interaction and expectations, as well as misconceptions. Traditional Chinese culture, for example, values shielding patients from discussing the full severity of an illness, which is in direct conflict with contemporary Western medical practices.

The most common cultural misconception among policy makers, program planners and service providers is an underestimation of the needs for formal support for ethnic elders. This misconception is based on the assumption that minorities “take care of their elder” within the family. Research does confirm that a significant proportion of minority elders live with their family. Unmarried older African Americans are twice as likely to live with family members as whites, Hispanic American and Asian American elders are three times as likely, and half of urban Native American elders live with family members (controlling for income, health status, and other characteristics).

There is reason to question whether the existence of a family living arrangement precludes the need for formal service support for minority elders. Research shows that the many responsibilities of minority families may make caregiving for ethnic elders overwhelming without any additional support. Clearly, health disparities, and other disparities which set racial and ethnic minority populations apart from the mainstream, are due, at least in part, to problems experienced in accessing and effectively utilizing health and human services. However, a solid and growing body of evidence indicates that one of the major reasons that services remain inaccessible and underutilized is because they are not responsive to the needs of the groups being served; they are not culturally competent.

Comprehensive research on health and social services and minority elders is scarce. Most of the research is done on health care service utilization because this can be readily measured. However, this is not enough. There needs to be a greater focus on other services. In addition, research is not available for all racial/ethnic groups for each type of service. For example, research varies what they compare. Some studies are linked to a single group. Other studies only compare between ethnic groups. Some compare within an ethnic group and others compare the minority population with the majority population.

Primarily, national data collection systems on the minority aging population are limited to the Bureau of the Census and the National Center for Health Statistics. Efforts are underway in the US Department of Health and Human Services, however, to incorporate collection of more racial and minority data in its many surveys and data collection instruments. For example, there is a large epidemiological study on the health of Mexican American elders in the southwestern United States, entitled the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiological Studies of the Elderly, or Hispanic EPESE.

Due to insufficient research and data, it is a challenge to fully generalize the research findings across the populations of ethnic elders. For example, simple rates of utilization of any service cannot necessarily be used to understand the health and socio-economic status of a population. Differences in service utilization across racial and ethnic groups can be understood only within the context of the status of the population measured.

A few selected studies provide a beginning foundation for scientifically-based evidence to support culturally competent social service and health care program design and development. The research indicates that both structural and cultural barriers exist that influence access, utilization, and acceptance of services. However, more research needs to be done on the effectiveness of different approaches and strategies.

The demographic composition of the United States population will change dramatically in the next few decades. Within the next ten years, the population will grow significantly older and more diverse. This demographic shift has important implications for direct service providers. A greater number of elderly individuals will be in need of health and human services. Racial and ethnic minority elders will constitute a growing proportion of this group. It is critical for direct service providers to be aware of the current and projected characteristics of this diverse population to prepare for addressing their changing needs into the future.

|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and nativity: 1999 to 2100; published January 2000 |

The United States is a nation with a rich mix of persons who come from different racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds. That mix is becoming even more dynamic. The minority older population will triple by 2030. By then, about one quarter of the elderly population will belong to a minority racial or ethnic group. In some parts of the United States, such as California, the upsurge in the number of older minority adults will be dramatic.

|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and nativity; published January 2000 |

Although the older populations will increase among all racial and ethnic groups, the Hispanic older population is projected to grow the fastest, from about 2 million in 2000 to over 13 million by 2050. In fact, by 2050, the Hispanic population age 65 and older is projected to outnumber the non-Hispanic black population in that age group.

| Percentage of the 65+ Population with a High School Diploma or Higher and a Bachelor’s Degree or Higher, by Race and Hispanic Origin, 1998 | ||

| High School Diploma or Higher | Bachelor's Degree or Higher | |

| Total | 67.0 | 14.8 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.6 | 16.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 43.7 | 7.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander | 65.1 | 22.2 |

| Hispanics | 29.4 | 5.4 |

| Source: March Current Population Survey | ||

Despite the overall increase in educational attainment among older Americans, there are still substantial educational differences among racial and ethnic groups. In 1998, about 72 percent of the non-Hispanic white population age 65 and older had finished high school, compared with 65 percent of the non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander older population, 44 percent of the non-Hispanic black older population, and 29 percent of the Hispanic older population. In 1998, 16 percent of non- Hispanic white older Americans had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 22 percent of older non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islanders.

In 1998, 73 percent of older men lived with their spouses, seven percent lived with other relatives, three percent lived with non-relatives, and 17 percent lived alone. Older women are more likely to live alone than are older men. In 1998, older women were as likely to live with a spouse as they were to live alone, about 41 percent each. Approximately 17 percent of older women lived with other relatives and two percent lived with non-relatives. Living arrangements among older women also vary by race and Hispanic origin. In 1998, about 41 percent of older white and older black women lived alone, compared with 27 percent of older Hispanic women and 21 percent of older Asian and Pacific Islander women. While 15 percent of older white women lived with relatives, approximately one-third of older black, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Hispanic women lived with other relatives.

|

| Source: March Current Population Survey |

Among older Americans, the poverty rate is higher at older ages. In 1998, poverty rates were nine percent for persons ages 65 to 74, 12 percent for persons ages 75 to 84, and 14 percent for persons ages 85 and older. Among the older population, poverty rates are higher among women (13 percent) than among men (seven percent), among the non-married (17 percent) compared with the married (five percent), and among minorities compared with non-Hispanic white persons. In 1998, divorced black women ages 65 to 74 had a poverty rate of 47 percent, one of the highest rates for any subgroup of older Americans.

|

| Source: March Current Population Survey |

Life expectancy varies by race, but the difference decreases with age. In 1997, life expectancy at birth was six years higher for white persons than for black persons. At age 65, white persons can expect to live an average of two years longer than black persons do. Among those who survive to age 85, however, the life expectancy among black persons is slightly higher than among white persons. The declining race differences in life expectancy at older ages are a subject of debate. Some research shows that age mis-reporting may have artificially increased life expectancy for black persons, particularly when birth certificates were not available. Other research, however, suggests that black persons who survive to the oldest ages may be healthier than white persons and have lower mortality rates. Data is not available on the life expectancies at different ages for the American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian and Pacific Islander populations.

| Life Expectancy by Age Group and Race, in Years, 1997 | ||

| White | Black | |

| Life Expectancy at Birth | 67.0 | 71.1 |

| Life Expectancy at Age 65 | 17.8 | 16.1 |

| Life Expectancy at Age 85 | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Source: National Vital Statistics System | ||

|

| Source: National Center for Health Statistics, CDC |

In 1997, the leading cause of death among persons age 65 and older was heart disease (1,832 deaths per 100,000 persons), followed by cancer (1,133 per 100,000), stroke (426 per 100,000), chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (281 per 100,000), pneumonia and influenza (237 per 100,000), and diabetes (141 per 100,000). Among persons 85 and older, heart disease was responsible for 40 percent of all deaths. In 1997, death rates were higher for older men than for older women at every age except the very oldest, persons age 95 or older, for whom men’s and women’s rates were nearly equal.

The relative importance of certain causes of death varied according to sex and race and Hispanic origin. For example, in 1997, diabetes was the third leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native men and women age 65 or older, the fourth leading cause of death among older Hispanic men and women, and ranked sixth among older white men and women and older Asian and Pacific Islander men. Alzheimer’s disease was the sixth leading cause of death among white women age 85 or older; however, it was less common among black women in the same age group or men of either race.

During the period 1994 to 1996, 72 percent of older Americans reported their health as good, very good, or excellent. Women and men reported comparable levels of health status. Positive health evaluations decline with age. Among non- Hispanic white men ages 65 to 74, 76 percent reported good to excellent health, compared with 67 percent among non-Hispanic white men aged 85 and older. A similar decline with age was reported by non-Hispanic black and Hispanic older men, and by women, with the exception of non-Hispanic black women.

In 1996, about seven percent of persons age 65 to 74 reported delays in obtaining health care due to cost, compared with five percent of persons age 75 to 84, and three percent of persons age 85 and older. Access to health care varied by race. In 1996, the percentage of older Americans who reported delays due to cost was highest among non-Hispanic black persons (ten percent), followed by Hispanic persons (seven percent), and non-Hispanic white persons (five percent). About two percent of non-Hispanic white persons reported difficulty in obtaining health care, compared with four percent of non-Hispanic black persons and three percent of Hispanic persons.

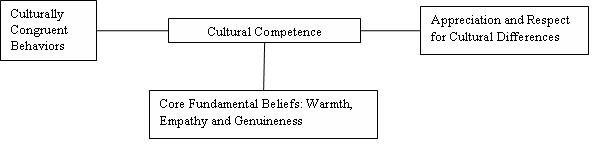

Culture plays a complex role in the development of health and human service delivery programs. As indicated earlier, the need for the provision of culturally appropriate services is driven by the demographic realities of our nation. Understanding culture and its relationship to service delivery will increase access to services as well as improve the quality of the service outcomes. Research has begun to provide the underpinnings for the development of standards for the delivery of services to diverse populations. The following principles are drawn from research material on the role culture plays in providing services to older adults. There is an ethic to culturally competent practice. When professionals practice in a culturally competent way programs that appropriately serve people of diverse cultures can be developed. Each person must first possess the core fundamental capacities of warmth, empathy and genuineness. This guidebook argues that to achieve cultural competence professionals must first have a sense of compassion and respect for people who are culturally different. Then, practitioners can learn behaviors that are congruent with cultural competence. Just learning the behavior is not enough. Underlying the behavior must be an attitudinal set of behavior skills and moral responsibility. It is not about the things one does; it is about fundamental attitudes. When a person has an inherent caring, appreciation and respect for others the person can display warmth, empathy and genuineness. This then enables the practitioner to have culturally congruent behaviors and attitudes. When these three essentials intersect, practitioners can exemplify cultural competence in a manner that recognizes, values and affirms cultural differences among their clients.

Culture shapes how people experience their world. It is a vital component of how services are both delivered and received. Cultural competence begins with an awareness of your own cultural beliefs and practices, and recognition that people from other cultures may not share them. This means more than speaking another language or recognizing the cultural icons of a people. It means changing prejudgments or biases you may have of a people’s cultural beliefs and customs. It is important to promote mutual respect. Cultural competence is rooted in respect, validation and openness towards someone with different social and cultural perceptions and expectations than your own. People tend to have an “ethnocentric” view in which they see their own culture as the best. Some individuals may be threatened by, or defensive about, cultural differences. Moving toward culturally appropriate service delivery means being:

Also, it means recognizing that acculturation occurs differently for everyone. This means more than different rates among different families from the same cultural background; it means different rates among members of the same family as well. For example, the beliefs, customs, and traditions of people from other cultures are often at odds with Western medicine and its heavy emphasis on science. Consistent with the Anglo-American emphasis on scientific reasoning, Western medicine tends to emphasize biological explanations for illness (such as bacteria, viruses or environmental causes) whereas in other cultures the natural, supernatural or religious/ spiritual reasons explain the cause of the problem (the yin and yang are out of balance; you have broken a taboo; or you have been thinking or doing evil).

Communication provides an opportunity for persons of different cultures to learn from each other. It is important to build skills that enhance communication. Be open, honest, respectful, nonjudgmental, and, most of all, willing to listen and learn. Listening and observational skills are essential. Letting people know that you are interested in what they have to say is vital to building trust. When giving presentations to minority groups, be prepared to spend time listening to needs, views and concerns of the community. Pay attention to what the community says and do not assume that you know what is best for the group or community you are addressing. Communication strategies have to capture the attention of your audience. This means not only using the language and dialect of the people you are serving; it means using communication vehicles that are proven to have significant value and use by your target audience. Multilingual brochures and other written material do not help those persons who cannot read no matter what language they are written in. In addition to traditional pathways such as television, radio and print media consider “moving” information through e-mail, Internet, and mass transit advertisements. Also remember that people can act as communication vehicles because of their ability to move through communities and connect with your target audience.

Keep the following points in mind when developing and using communication vehicles:

Community can be defined in several different ways. It can refer to the people who live within a geographic boundary. It can refer to those who are served by a certain agency or program. It can also refer to a group of people who have similar beliefs, a similar culture or shared identity and experiences. Getting to know the community, its people, and its resources will help you identify useful strategies for service delivery. If the church is an important institution in a particular community, developing a preventive health partnership with the church may help you reach a group of people that you are trying to serve.

Establish partnerships and relationships with key community resource people. Put accurate information and adequate print materials into the hands of people who can actively promote your interests. Try to report back the results or outcomes of your initiatives to any groups or individuals that help you in the process. People will feel more vested in initiatives when they know about outcomes that they have helped to achieve and will be more likely to assist you again. Keep the following points in mind:

Culturally and linguistically friendly interior design, pictures, posters and art work make your facilities more welcoming and attractive to the consumer. Providing services in a comfortable setting enhances program participation. Display material and information through the use of props that are recognizable, hold significance, value, and interest to your target audience. Use color, print size, language and pictures on props that will attract attention. Put this material in the hands of people that will maximize their distribution and circulation.

|

Principles of Interpreter Services

(Adapted from Jane Perkins et al., Empowering Linguistic Access in Health Care Settings: Legal Rights and Responsibilities. Published by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, January 1998, p. 89.) |

Cultural and linguistic competence must be infused throughout everything organizations and individuals do. Policies, planning, structures and procedures must be the underpinning and support for culturally competent services at the community level. This includes:

The driving force behind cultural competency is population-based service delivery; i.e., knowing and understanding the people that you serve. It means appreciating the importance of culture, while avoiding stereotypes. It means understanding the sociopolitical influences that helped to shape your consumers’ attitudes, beliefs and values. It means that cultural awareness efforts are a part of a system-wide program within your organization. It is a process that is continually evolving.

|

The Cultural Sensitivity Continuum

|

Staff development is essential to both cultural and linguistic competence. Staff attitudes and beliefs can be in conflict with the values of the people that you are trying to serve. It is important, therefore, to provide informal opportunities like “Brown Bag” lunches for staff to explore their attitudes, beliefs and values. Finally, it is important to recognize that cultural sensitivity is a continuum. Where staff are on the continuum may be different with each minority group.

Also, specialized training for staff involved in the interpretation process is often overlooked. There is an assumption that if you are bilingual you can interpret. Training bilingual staff in interpreter skills enhances their ability to effectively communicate in both directions.

Developing culturally appropriate programs is an evolving process. In a society as diverse as the United States, health and social service providers and others in the delivery of services to older persons need the ability to communicate with diverse communities. They need the knowledge to understand culturally influenced behaviors. In this regard there are five essential elements that contribute to an organization’s ability to become more culturally competent.

There are three main points of influence at which a provider can create culturally competent interventions – the macro, mezzo, and micro levels. The first point of intervention is at the macro level. This level of influence includes policies, laws, and regulations. Examples of macro level interventions include Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, Executive Orders, Healthy People 2010, and the Older Americans Act, as well as accrediting organizations for managed care and health care organizations, such as NCQA and JCAHO.

The second point is the mezzo level, which is the community-based involvement in the design and delivery of programs and services. Examples of mezzo level interventions include community-based organizations, such as churches, schools, civic organizations, and social organizations.

The micro level is where individual providers understand the importance of cultural competency and are trained to serve in a culturally competent manner. Micro-level interventions prepare health and other professionals to interact effectively and appropriately with individuals from diverse cultures. Examples include understanding the values, attitudes, and beliefs of others and demonstrating culturally congruent behaviors.

In general the research indicates that culturally competent service delivery includes these attributes.

Culturally appropriate service delivery incorporates an understanding of the needs of the ethnic elders and the types of services provided. For health services, the characteristics of the individual that need to be measured include health status, functional level, and the level of acuity, and health conditions. This understanding can be maximized by using multidisciplinary assessment methods, comprehensiveness in assessing the problems, a rehabilitative approach, and service provision longevity.

Culturally accessible service delivery in essence “opens the door” to services for minority elders. Culturally acceptable services are those that ethnic elders would want to walk through the door to receive. Many service doors have signs that say welcome but the place is not culturally competent. Opening the door requires that services be located in the community where the elders live and that admission procedures do not exclude elders based on such criteria as immigration status and language ability.

Culturally accessible service delivery is created by addressing the structural barriers, which includes affordability, availability of service hours, location of service, transportation, as well as outreach and public information. An example of cultural inaccessibility is Native American elders’ abhorrence of the ‘white’ tape that surrounds services and elders’ unwillingness to accept services delivered as charity.

To create culturally acceptable services, cultural barriers must be addressed. These include consideration of ethnic factors, such as language, religion, family, and acculturation. Some provider interventions include: outreach, translation, interpretation, transportation, cultural training for health professionals, and the use of bilingual/bicultural para-professionals.

There is a demographic imperative to improve the health and longevity of minority elders through the provision of culturally sensitive programs and services tailored to meet the differing racial/ethnic needs of minority elders. It is necessary to understand and internalize cultural concepts, utilize research-based evidence regarding effective service delivery, and address structural and cultural barriers in designing culturally competent service. Research studies indicate that populations differ and service providers need to identify and incorporate these differences into their programs. However, the studies also indicate that to focus exclusively on between-group differences without appreciating between-group similarities does not lead to appropriate design and implementation. Thus, service providers must appreciate not only how groups differ, but also how they are alike in designing culturally sensitive services.

Culturally competent service providers must take into account the full range of factors that influence how any one individual service recipient behaves and communicates.

The two levels of influencing factors are:

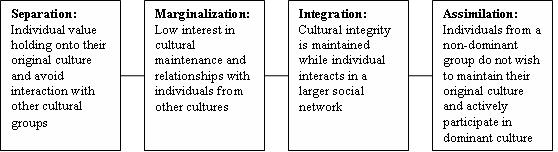

Acculturation is a process that occurs when two distinct cultural groups have continuous first-hand contact, resulting in subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups. The degree to which acculturation takes place is influenced directly by both the cultural and individual-level differences. The following examples are provided to illustrate this process and the type and level of influence that specific socio-cultural variables may have in a given situation.

Continuum of Acculturation

One of the difficulties that has presented itself to direct service providers over the years is the development of a relationship with service recipients that supports the achievement of positive outcomes. The key to success in developing this type of relationship is to practice the underlying behaviors that make such relationships possible.

The positive outcomes associated with the communication of these characteristics are sought by providers across numerous settings and with a wide variety of service recipients. The presence of these relationship qualities has been shown to influence the individual’s overall level of health.

A strong focus on the development of these characteristics must be at the heart of delivering culturally competent services. Studies show that these “characteristics” can be learned by direct service providers. Systematic training is necessary in which each of the three characteristics is studied independently.

The core facilitative characteristics of a culturally competent service provider include:

Warmth: Acceptance, liking, commitment, and unconditional regard.

Empathy: The ability to perceive and communicate, accurately and with sensitivity, the feelings of an individual and the meaning of those feelings.

Genuineness: Openness, spontaneity, and congruence—the opposite of “phoniness.”

Following are examples of culturally competent service delivery that exhibit the facilitative characteristics of warmth, empathy and genuineness. These examples are provided to illustrate a few of the ways in which service providers have practiced these behaviors to provide culturally competent services.

Source: Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging