![]()

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| The effects of alcohol and other drug abuse on women's health are clear. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

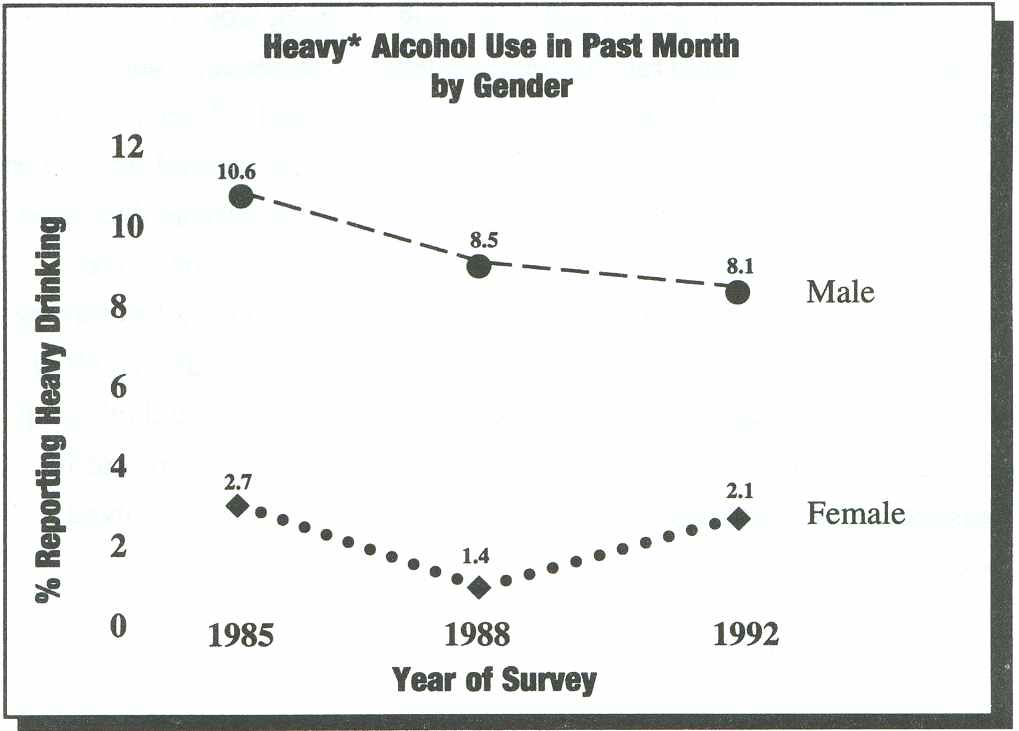

Alcohol is the substance most commonly abused by the general population and by women. The trends in abuse of alcohol by women are not encouraging. For example, although heavy use declined between 1985 and 1992, the decrease was slight, and reported heavy use increased by more than one-third between 1988 and 1992.11 According to the 1992 NHSDA, 2.1 percent of women aged 12 and over had engaged in heavy alcohol use in the month prior to the survey (see Figure 1).12 The 1988 National Health Interview Survey (the most recent one for which data are available), found that seven percent of female respondents13 (or an estimated 6.6 million women) 14 drank at heavy levels in the two weeks prior to the survey. A 1984 national survey of alcohol problems found that six percent of women reported at least a moderate problem with alcohol and sixteen percent reported at least a minimal problem with alcohol. 15 In 1990, the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) estimated that "alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence are serious problems that affect about 10 percent of adult Americans." 16 Given an estimated adult female population (women aged 12 and over) of approximately 107 million in 1992, it can be estimated that as many as 10.7 million American women may abuse alcohol.

Figure 1

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 121. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 117. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1985, 70.

Heavy alcohol use was reported by 6.5 percent of young women aged 18 to 25 and 0.5 percent of adolescent girls aged 12 to 17. 17 In terms of population estimates, this indicates that nearly 921,000 young women and more than 50,000 adolescent girls engaged in heavy drinking in 1992.18

The survey also reported that 12.3 million women, or 11.5 percent of women aged 12 and over, consumed alcohol at least once a week. Women 18 to 25 and 26 to 34 are more likely to consume alcohol once a week than those 35 and over (16 percent, 14.5 percent, and 10.9 percent respectively). 19 Given that these are primary childbearing years, this figure is noteworthy. In fact, the 1992 NHSDA also found that 40.4 percent of the women aged 12 and over reported consuming alcohol in the previous month. More than half (53 percent) of the women 18-34-the prime childbearing years-reported alcohol consumption in the previous month. Also of concern is the finding that one in seven adolescent girls (14.5 percent) reported consuming alcohol in the previous month.20

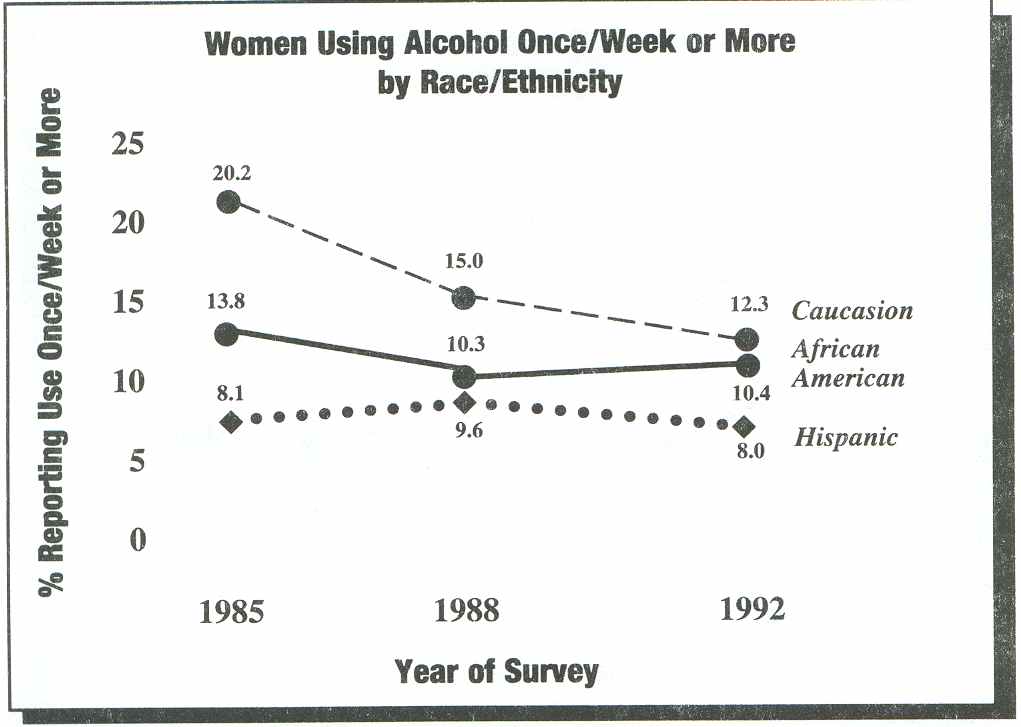

Figure 2

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 121. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 117. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1985, 70.

As Figure 2 shows, Caucasian women are slightly more likely to use alcohol once a week or more than African American women (12.3 percent compared to 10.4 percent) and much more likely than Hispanic women (8 percent).21

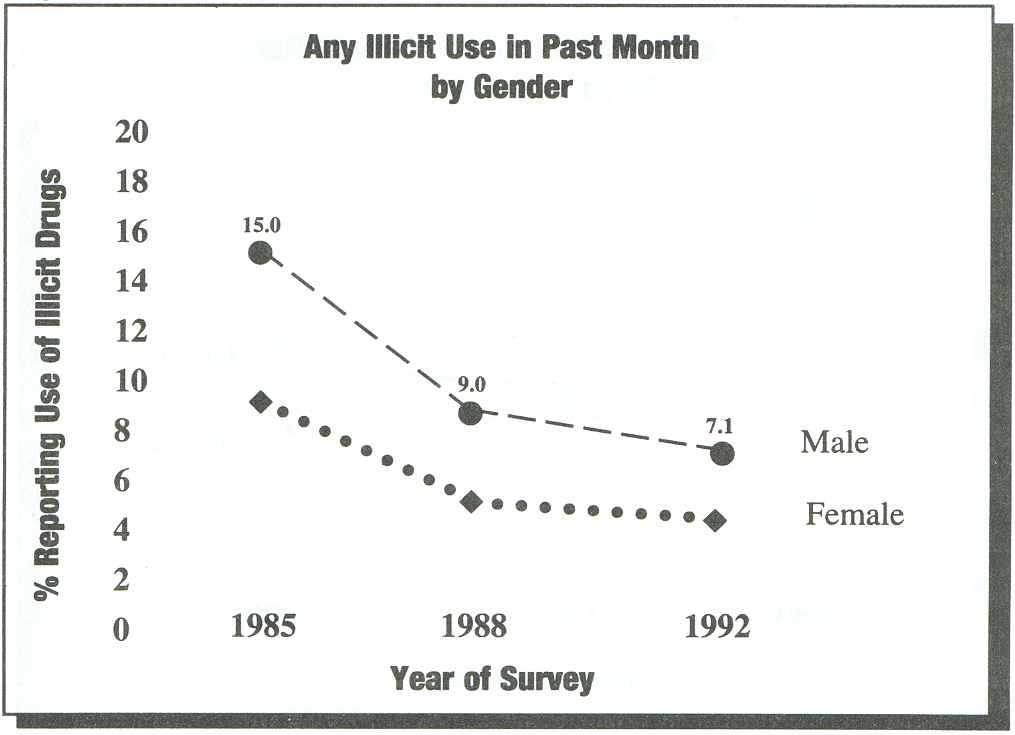

Figure 3

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 19. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 17. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1985, 54.

A number of researchers report differences in drinking patterns by gender. For example, men report higher quantity, frequency, and rates of intoxication at an earlier age then do women and experience more lifetime symptoms on average.22 As Figure 1 shows, the gender difference in reported heavy alcohol use decreased from 1985 to 1992. While heavy use by men has steadily declined during this period, heavy use by women actually increased from 1988 to 1992.

According to the 1992 SAMHSA Survey on Drug Abuse, slightly more than 4 percent of female respondents over the age of 12 had used an illicit drug in the previous month, representing an estimated 4.4 million women (see Figure 3) .23 This estimate is still significantly lower than the use reported by men (7.1 percent). The use by women between 1985 and 1992 declined by 44 percent, slightly lower than the decline in use by men (47 percent).

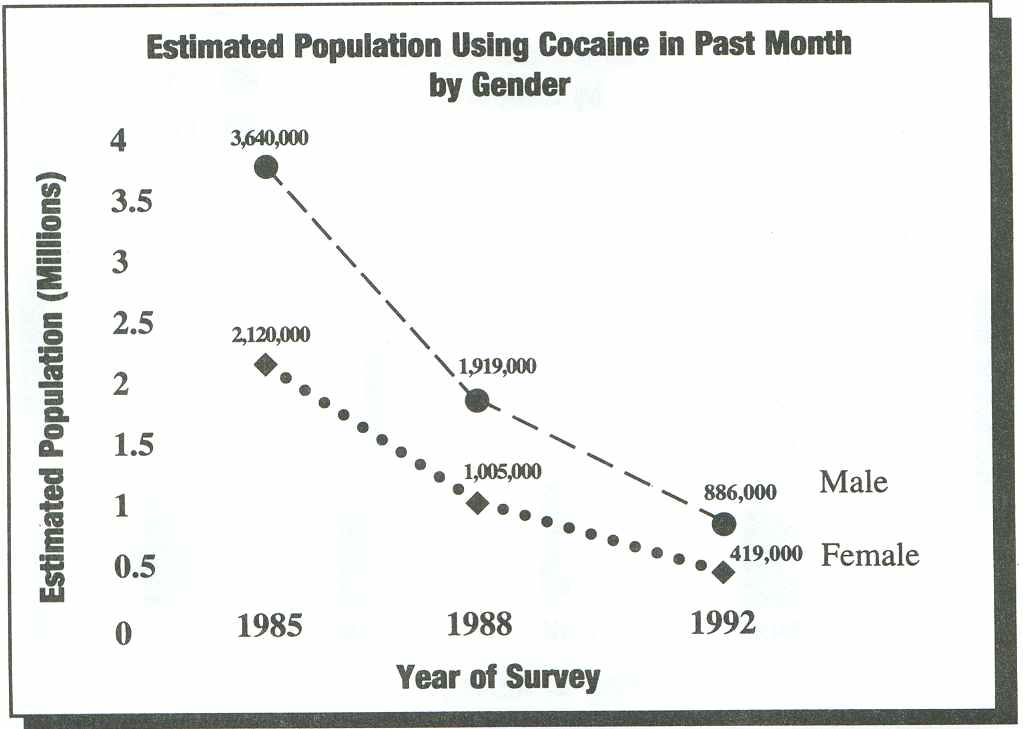

Figure 4

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 31. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 29. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1985, 14.

Most of these women-2.9 percent of the female respondents or an estimated 3.1 million women-had used marijuana in the past month ,24 and an estimated 419,000 women had used cocaine in the past month (see Figure 4).25

According to the 1992 NHSDA, an estimated 98,000 women used crack in the past month; however, the number of responses is too small for this estimate to be reliable.26 As Figure 4 shows, although reported cocaine use by women decreased substantially between 1985 and 1992, an estimated 419,000 women had used this drug in the month prior to the 1992 NHSDA.

Figure 5

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 104. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 102. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1985, 9.

Notably, for Caucasian women and Hispanic women the decrease in cocaine-related episodes in emergency rooms between 1988 and 1991 was substantially higher (37 percent and 32.7 percent, respectively), than for the population overall (27 percent). For African American women, the decrease was substantially lower-16 percent.27

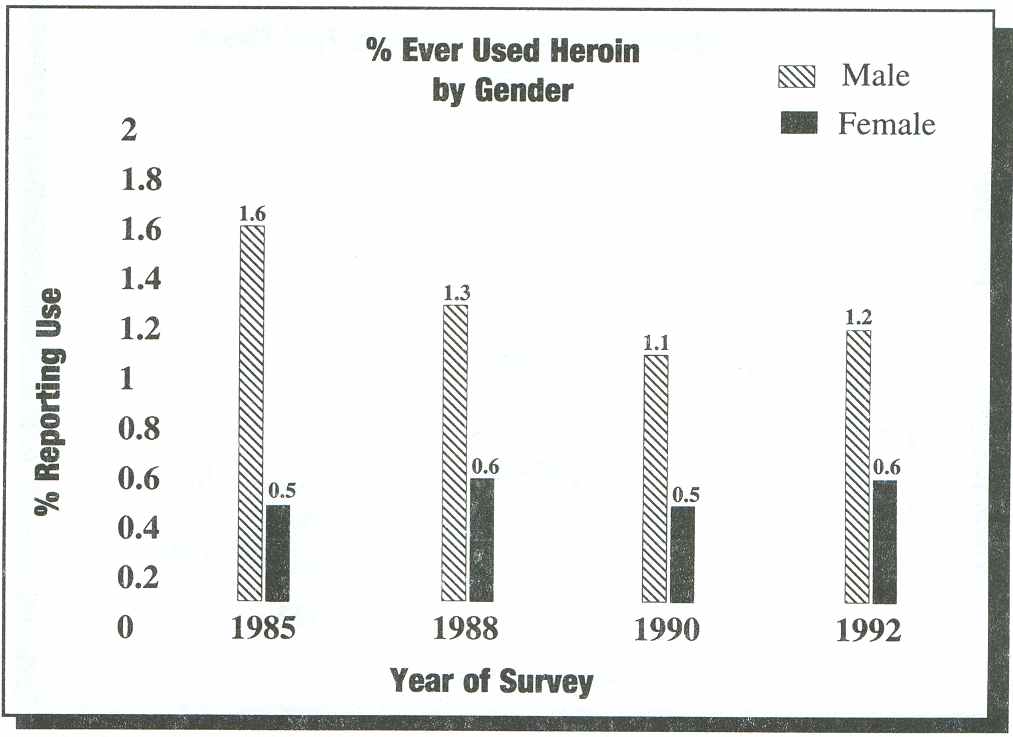

Only one-tenth of 1 percent (or 0. 1 percent) of female respondents reported using heroin in the past year, but this translates into an estimated 88,000 women. In contrast, 0.2 percent of men (an estimated 236,000) reported using heroin in the past year. Moreover, 644,000 women, or 0.6 percent of the population of women 12 years of age and older, reported ever having used heroin, compared to 1.2 million men, 1.2 percent of the male population 12 years old or older.28

Figure 6

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 55. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1998, 53.

Unfortunately, because the prevalence estimates are so small, it is not possible to compare heroin use by women and men in different age groups or among women in different age groups. However, an estimated 27,000 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 used heroin in the past year, as did 152,000 young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 .29 This is particularly disturbing because household surveys underreport the use of illegal drugs. As with several other estimates from the NHSDA, the samples are too small to ensure reliability.

According to the NHSDA, the proportion of women reporting lifetime heroin use has remained relatively constant over the last seven years (see Figure 5).

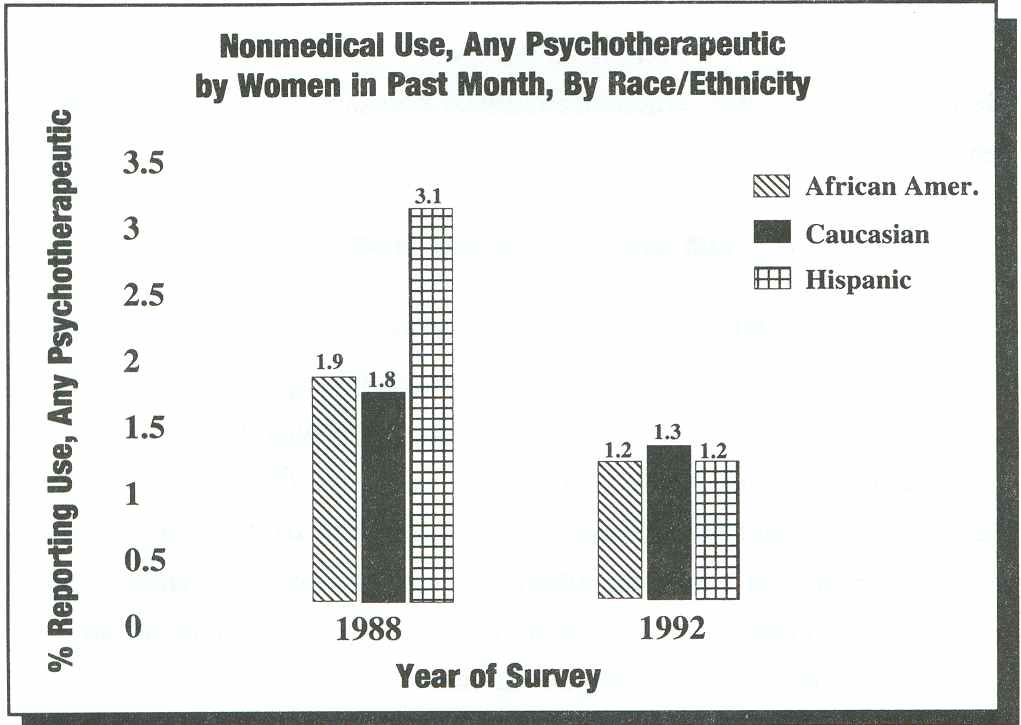

The 1992 NHSDA indicates that an estimated 1.3 million women (1.2 percent of female respondents) used psychotherapeutic drugs for nonmedical reasons during the month before the survey.30 This figure indicates a 35 percent decrease in reported use since 1988 (see Figure 6).31 These data represent rates of nonmedical use of prescription drugs, defined in the survey as "on your own, either without your own prescription from a doctor, or in greater amounts or more often than prescribed, or for any reason other than a doctor said you should take them."

| Twice as many women as men receive and use prescriptions for drugs |

Although some studies have demonstrated that women are much more likely than men to abuse psychotherapeutic drugs (defined by SAMHSA to include stimulants, sedatives, tranquilizers, and analgesics), the 1992 NHSDA shows no statistically significant differences: An estimated 1.3 million men (1.3 percent of male respondents) reported nonmedical use in the previous month .32 However, the possibility of nonmedical use of prescription drugs is greater for women than for men. Twice as many women as men receive and use prescriptions for drugs; women receive more multiple and repeat prescriptions than men; and women are more likely than men to receive prescriptions for excessive dosages.33

| Women are twice as likely as men to be addicted to prescription drugs in combination with alcohol. |

According to Roth, approximately "70 percent of the prescriptions for tranquilizers, sedatives, and stimulants are written for women." Moreover, "women are twice as likely as men to be addicted to prescription drugs in combination with alcohol." 34 Given the health risks of combining alcohol with prescription drugs, this fact represents a serious health problem for women.

Although only 5.3 percent of the 1991 NHSDA respondents reported using alcohol in combination with other drugs in the previous month, 13.9 percent were 18 to 25 years old. Moreover, 1.4 percent reported using three or more different substances in the past month.35 Unfortunately, gender-disaggregated data for polydrug use (also referred to as co-occurring drug dependencies) are not reported by SAMHSA. However, according to Ross, alcoholic women in treatment are more likely to be abusing barbituates, sedatives, or minor tranquilizers at the time of entry into treatment than alcoholic men, who are more likely to be abusing marijuana. 36

During 1992, 2.8 million people needed substance abuse treatment, 37 but there were fewer than 600,000 treatment slots at any given point in time. Unfortunately, data on the number of women in treatment versus treatment capacity needs are not readily available.

According to the 1990 Institute of Medicine report on alcohol problems of women, specialized treatment programs for women in the U.S. increased only slightly between 1982 and 1987 from 23 percent to 28 percent of the nearly 5,800 programs reporting to NIDA/NIAAA. 38 Nonetheless, women are increasingly entering treatment, as evidenced by several data sets and as reported by the Institute of Medicine.39 For example, the 1990 survey of the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (NASADAD) revealed the following information on the 1.2 million admissions to 7,743 treatment units:,

|

22.3 percent of admissions for treatment of alcoholism were women; | |

|

33 percent of admissions to programs for treatment of other substance abuse were women; and | |

|

younger clients admitted for treatment of alcoholism were more likely to be women than those in older age groups (38 percent in the under 18 age group, versus 18 percent in the 45 to 54 and 55 to 64 age groups).40 |

Of clients admitted for treatment of other substance abuse, however, 41 percent of those 18 and under were female, and women consistently represented 26 percent to 37 percent of the age cohorts. In fact, 37.2 percent of those over 65 were women .41 Notably, these data indicate that women are under-represented in the treatment population. Moreover, because the proportion of women in treatment has not substantially changed in over a decade, it is clear that the dearth of treatment slots for women continues to be a serious problem.

According to the 1990 Drug Services Research Survey (DSRS) of 120 substance abuse treatment programs, approximately 25 percent of the 2,182 clients in the sample were women. Notably, 33.5 percent of clients in methadone treatment programs (serving heroin addicted persons) were women while 20 percent of those in programs treating alcohol addiction only were women.42 According to the 1992 NHSDA, 27 percent of those reporting heroin use in the previous month were women 43 and 22 percent of those reporting heavy drinking in the past month were women.44 A 1992 evaluation of a Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) demonstration project for Medicare coverage of alcoholism services found that 20 percent of the 2,977 clients enrolled in the study were women. In that study, women were more likely to be enrolled in outpatient programs (26 percent) and less likely to be enrolled in the combined inpatient and outpatient treatment programs (17 percent). 45 In 1992, approximately 35 percent of persons participating in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) programs were women; 43 percent of those 30 and under were women.46

Patterns of substance abuse for both women and men vary age, race/ethnicity, educational status, and employment status.

Patterns of alcohol and other drug use vary by age group for both women and men. According to the 1992 NHSDA, for example, the proportion of female respondents aged 18 to 25 who reported having used any illicit drug in the month before the survey was higher than respondents in the 12 to 17 and 26 to 34 age categories: 9.5 percent versus 6.5 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively. The proportion was significantly lower for those age 35 and over (1.4 percent).47 Women in the age groups 18 to 25 and 26 to 34 were much more likely to have abused any psychotherapeutic drug in the previous month (2.2 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively) than those 12 to 17 (1.8 percent) and over 35 (.6 percent).48 Young women 18 to 25 were most likely to have engaged in heavy drinking: 6.5 percent versus 2.1 percent for female respondents overall.49

Furthermore, according to the 1992 NHSDA, adolescent girls, aged 12 to 17, were about as likely to have used an illicit drug in the previous month as adolescent boys (661,000 adolescent girls or 6.5 percent, compared to 608,000 adolescent boys or 5.7 percent).50In some studies of high school students, teenage girls are less likely to identify themselves as drinkers than teenage boys, but the degrees of difference vary. Some studies show very small differences. Age of first use and age of onset of problems among girls are decreasing. Most adolescents (regardless of gender) are introduced to alcohol between the ages of 10 and 15, usually with parents at home during a meal, a celebration, or a ceremony, but without any discussion of appropriate use .51 This method of introduction may vary by culture.

Use of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine has decreased among female high school seniors since 1985; for example, in that year, 8.2 percent of female students reported having used cocaine in the previous month-by 1990, that proportion had decreased to 3.3 percent. However, it is important to note that there is no comparable survey of high school dropouts, a highly vulnerable population for substance abuse.52 According to a 1992 survey of 8th and 10th grade students, there are few gender differences in the use of drugs. This may be because female students tend to date older male students who are more likely to use drugs. There is little male-female difference in 8th and 10th grades, respectively, in the use of inhalants, cocaine, and crack. As with adults, stimulant and tranquilizer use are higher among adolescent females .53

Although socioeconomic factors are increasingly viewed as related both directly and indirectly to substance abuse, research-based data are scarce, and many of the published reports are based on data that are at least 10 years old. Few studies that would provide adequate data on which to ascertain socioeconomic factors related to substance abuse have been funded by either the public or private sector. However, data from the SAMHSA survey and other sources demonstrate some associations between prevalence of abuse of alcohol and other drugs and various indicators of socioeconomic status, including education, employment, and income levels. Importantly, the relationship among these factors is seen as having changed over time. For example, according to Galbraith:

the misuse of legal drugs was once thought to be the domain of middle- and upper-class women who could afford psychiatrists. Some prevention programs, however, are reporting high rates of misuse among women in low-income communities as a result of doctors' writing prescriptions for women on Medicaid, sometimes in lieu of a thorough medical assessment.54

Women who are unemployed are at higher risk of becoming heavy drinkers, while women who are drinking but who work full-time outside the home evidenced fewer alcohol dependence symptoms than those working in part-time jobs.55 However, this finding may be misleading because women who are at higher risk of becoming heavy drinkers may be more likely to be unemployed because they have already begun to experience problems associated with drinking (e.g., tardiness or absence from work). In a study that included both Caucasian and African American women entering treatment for heroin addiction, most of the women lacked education and job experience. 56

Among older women, there are clear relationships between abuse of prescription drugs and education and income. One researcher reports "higher rates of frequency and duration of use among older, unemployed, and less educated women."57 However, the author does not indicate how "unemployed" is defined; that is, whether this term includes retirees or those whose income is normally derived from employment; nor does she indicate if adjustments were made for those beyond the age of retirement (generally, 65 or over). These findings also reportedly conflict with the clinical experience of treatment program personnel.

This section describes the physiological and the psychological effects of substance abuse on women. This information is critical to understanding the medical and mental health needs and service requirements of women in treatment.

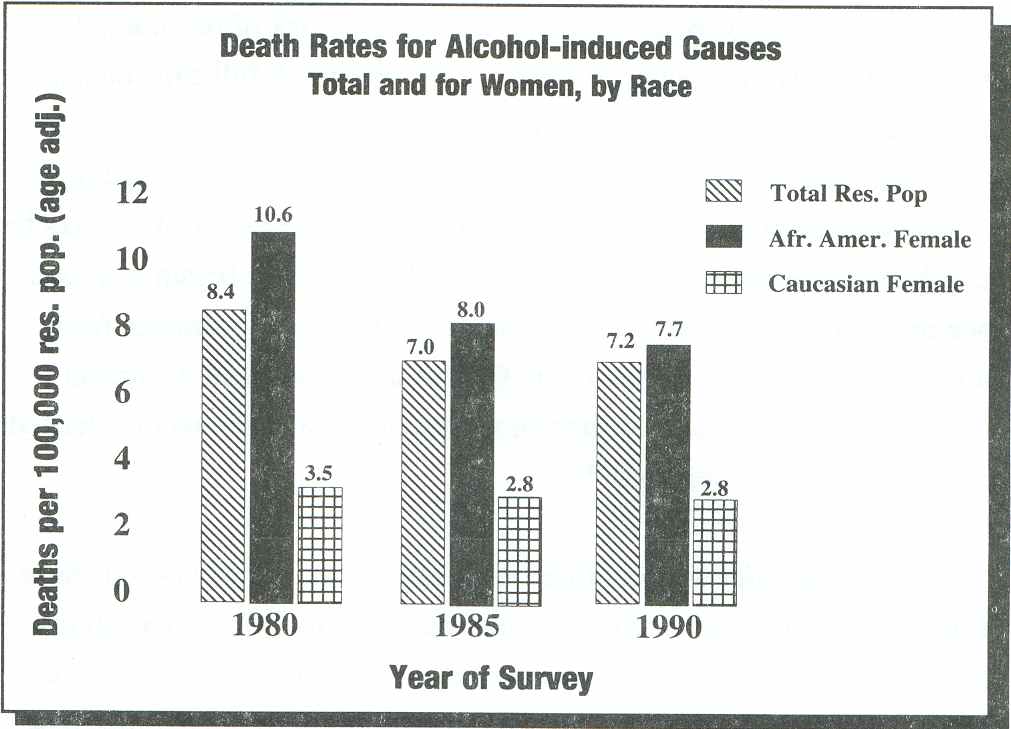

Figure 7

Health United States and Healthy People 2000 Review 1992, 56.

| Women suffer severe physiological consequences as a result of substance abuse. |

Women suffer severe physiological consequences as a result of substance abuse. However, because much more data are available on the effects of alcohol abuse than that of other drugs, the focus of this section focuses on physiological consequences of alcohol abuse. As was mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, in 1990, the death rate associated with alcohol-related causes was 2.8/100,000 for Caucasian females and 7.7/100,000 for African American females. The death rate for other drug induced causes was 2.5 per 100,000 for Caucasian women and 3.4 per 100,000 for African American women. Notably, the alcohol-induced death rate for African American females is higher than that for the total population (see Figure 7)58.

The medical consequences of alcohol abuse and alcoholism are many, as is evidenced by a number of data sources. For example, alcohol- related medical consequences presented by 20 percent or more of all admissions to short-stay hospitals from 1979 to 1984 included the following: thiamine deficiency (66 percent); liver abscess and sequelae of chronic liver disease (56 percent); varicose veins (other than lower extremities); hemorrhoids; phlebitis or other venous thrombosis (49 percent); spinocerebellar disease (29 percent); hypothermia (25 percent); necrosis of the liver (23 percent); and diseases of the pancreas (20 percent) .59 Heavy alcohol use has also been associated with peptic ulcers ;60 nutritional deficiencies affecting anemia; neuropathy; depressed cellular and hormonal functions;61 hypertension; ischemic heart disease; cerebrovascular disorders; 62 cancer of the liver; esophagus; nasopharynx; and larynx;63 and neurologic disorders.64

The degree of gender disparity in the prevalence of all of these medical consequences is not fully known. However, differences in susceptibility to alcohol- related liver damage have been identified. For example, women have been found to develop severe liver disease with shorter durations of alcohol use and lower levels of consumption than do men, and alcohol-dependent women have a higher prevalence and greater severity of alcohol-related liver disease than do their male counterparts. Women with alcohol problems are disabled more frequently and for longer periods than are men, and women have higher death rates from alcohol- related damage.

| Women with alcohol problems are disabled more frequently and for longer periods than are men, and women have higher death rates from alcohol- related damage. |

In women, alcohol reaches higher peak levels in the blood faster than it does for men, even when the same amount of absolute alcohol per pound of body weight is consumed. There are several reasons for this difference in alcohol metabolism. In general, a woman's body has a higher ratio of fat-to-water composition. Women who use oral contraceptives show slower rates of alcohol metabolism. Recent research has also identified gender differences in the stomach's capacity to oxidize alcohol.65

Heavy alcohol consumption also has been linked to osteoporosis (more common in women than in men)66 and reproductive difficulties (e.g., infertility, amenorrhea, failure to ovulate, dysfunction in the post-ovulation phase of the menstrual cycle, pathologic ovary changes, premenstrual syndrome, and early menopause). However, the reasons for these links are not known.67

Research indicates that the chronic female drinker not only has a decrease in sexual functioning, but she also experiences serious sexual dysfunction. Researchers also have found relationships between alcoholism among women and sexual dysfunction, including high rates of anorgasm. The studies do not usually identify the onset of sexual dysfunction in terms of progression of the woman's alcoholism.

The remainder of this section (2.3.1) summarizes information on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and tuberculosis (TB) among women, as they relate to substance abuse.

| STDs have a particularly significant impact on women who suffer more frequent and severe long- term consequences than men. |

STDs have a particularly significant impact on women who "suffer more frequent and severe long-term consequences than men ... because women tend to show fewer symptoms and as a consequence they go untreated for longer periods of time."68 STDs are of particular concern with respect to pregnant women because the "transmission of an STD to an unborn child or during childbirth can have devastating effects."69

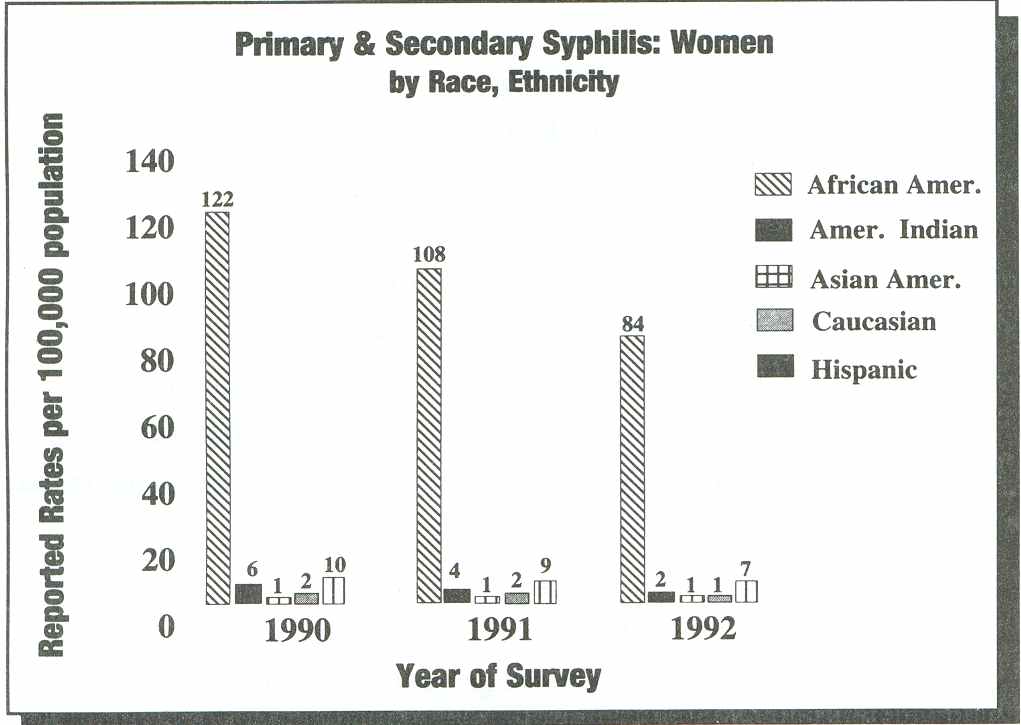

During the 1980s, reported rates of primary and secondary syphilis for both genders increased dramatically in the United States, from 13.7/100,000 population in 1981 to 20.3/100,000 in 1990.70 In 1991, the rate began to decline; in that year, it was 17.3/100,000 and in 1992 it fell again to 13.7/100,000. The rate of primary and secondary syphilis among women was 17.5, 15.4 and 12.2/100,000 in 1990, 1991 and 1992, respectively.71 However, the rates for Caucasian women were far lower than those for African American, Hispanic, and American Indian women in the same years, as Figure 8 shows.

Figure 8

Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992, 166-167.

While the rate of gonorrhea among women decreased from 247. 1/ 100,000 in 1988 to 175.5/100,000 in 1992, it is still a disturbing incidence. Moreover, as for syphilis, the race/ethnic differences are significant. For example, in 1992, the most recent year for which race/ethnic data are disaggregated for women, the rates per 100,000 population were: 43.0 for Caucasian women, 1,130.8 for African American women, 119.6 for American Indian women, 26.6 for Asian American women, and 92.5 for Hispanic women. 72

The rate of chlamydia in women, which can result in serious reproductive track complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy, more than doubled in the five year period from 1988 to 1992, from 133.5/100,000 to 270.0/1 00,000.73 The rate of congenital syphilis among infants less than one year of age increased from 3.0/100,000 live births in 1980 to 44.7/100,000 in 1990.74 The rate more than doubled from 1989 to 1990 (to 91.0/100,000 live births),75 although this is reportedly in large part a result of a change in the case definition used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). After increasing to 107.5/100,000 live births in 1991, the rate of this STD, which is among the most prevalent, decreased to 94.7/100,000 in 1992.76

An important consideration for prevention and treatment programs is that STD rates differ significantly by geographic area of the country. In New York City, for example, a 500 percent increase in reported congenital syphilis was reported between 1986 and 1988.77 Data are not generally available on the incidence of STDs among women who abuse alcohol or other drugs.

AIDS was the second leading cause of death for American women between the ages of 25 and 44 in 1992,78 and women constitute nearly 12 percent of cumulative diagnosed cases of AIDS .79 According to the CDC, as of March 1993, 32,477 women (11 percent of the total diagnosed cases) have AIDS. More than 100,000 women are infected with HIV.80 CDC reports indicate that 75 percent of women and 80 percent of children with AIDS are members of a racial or ethnic minority population. More than half of women diagnosed with AIDS are African American (53 percent), and 20 percent are Hispanic. Of pediatric cases, 55 percent are African American, and 24 percent are Hispanic.81

Although HIV infection is a major health problem for women, many cases may be undiagnosed by physicians because they are unaware of the signs and symptoms in women. The 1992 change in the case definition of AIDS, which broadened the scope of opportunistic infections associated with AIDS, has been an important factor in recognizing the disease's impact on women. However, death rates among women who are HIV-positive are higher than those for men, perhaps because of late clinical identification of HIV infection. It should also be noted that the adverse effects of chronic alcohol use on the immune system may increase rates of progression from HIV to AIDS in women.82 Since many women die before an HIV diagnosis is made, the numbers of women with HIV may be considerably higher than those reported.

Women who inject drugs and/or who have been the sexual partners of past and present injection drug users are at greatest risk for HIV infection. Nearly half of women with AIDS (49 percent) inject drugs. An additional 21 percent are sexual partners of injection drug users. Of the pediatric cases, 39 percent result from a mother's injection drug use and 17 percent from the mother having had sex with a partner who injected drugs.83

| Women who inject drugs and/or who have been the sexual partners of past and present injection drug users are at greatest risk for HI V infection. |

Although the public health community has concentrated on the relationship between injection drug use and HIV, there is growing evidence of a need to recognize the relationship between the use of any mind-altering substance and high- risk sexual activity. For example, one study in Florida reported a strong relationship among the number of sexual partners, drug use, condom use, and HIV- seropositivity.84 Among the 50 drug users in the study, only one was injecting drugs. Ninety-seven percent were current users of crack, and, for the group as a whole, about 50 percent had either HIV or AIDS. In fact, numerous recent studies suggest that women who use crack cocaine may be at equal or greater risk for HIV and other STDs than injection drug users. Accumulating evidence links increases in syphilis rates and HIV infection to the crack cocaine epidemic and indicates that crack cocaine users have significantly higher rates of STDs than nonusers.85 According to Sterk and Elifson, for example, women who use crack cocaine may have a higher rate of sexual encounters, are more likely to engage in unsafe sex than women who use other drugs, and may trade sexual favors or engage in prostitution to obtain drugs.86 These women are also more likely to contract STDs, which are linked with high HIV infection rates.

| A woman who uses any mind-altering drug (including alcohol) can be at risk for STDs. |

A woman who uses any mind-altering drug (including alcohol) can be at risk for STDs (as well as HIV and unwanted pregnancy) because her inhibitions are eased and her decision-making ability is altered. Even if she would otherwise intend to refrain from risk-taking behavior (e.g., multiple partners or unprotected sex), she might engage in such behavior while under the influence of alcohol, crack cocaine, cocaine, marijuana, or other drugs. Moreover, the compulsive use of drugs may increase a woman's risk for STDs if she engages in sex for drugs or for money to buy drugs.

Cases of tuberculosis (TB), once considered nearly eradicated in the United States, are increasing at an alarming rate for the population overall. According to the CDC, nearly 9,000 women, most between the ages of 25 and 44, were reported with verified cases of TB in 1993. African American women have the highest rates of TB followed by Asian American and Hispanic women .87 Foreign-born women, who account for nearly one-third of reported TB cases are disproportionately represented. Women with HIV infection and homeless women are at especially high risk for contracting TB. Furthermore, injection drug users have higher rates of TB whether or not they are HIV-positive.88

The term "dual diagnosis" is applied most often to the co-occurrence with substance abuse of major psychiatric disorders; in women, these are usually depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders. It is important to note that women addicted to alcohol and/or other drugs may, early in the recovery process, present with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and mood disorders. These may be temporary conditions associated with withdrawal symptoms. For clients with bipolar affective disorder, appropriate use of lithium has not been found to interfere with recovery from addiction to alcohol or other drugs.

| Substance abuse and mental health problems often coexist and must be addressed simultaneously. |

The concept of dual diagnosis is controversial. This controversy has been fueled by the way alcoholism treatment specialists and mental health providers perceive and treat substance abuse problems. The problem has been exacerbated by a lack of understanding of the nature of co-occurring disorders by many physicians who have prescribed sedatives/ hypnotics or tranquilizers to women already experiencing alcohol and other drug problems.89 Practitioners in both fields are now recognizing that substance abuse and mental health problems often coexist and must be addressed simultaneously, with particular interest "in the relationships between specific psychiatric syndromes and alcohol problems, primarily depression and antisocial personality disorder."90 Clinical researchers distinguish "between those persons with an alcohol problem who were found to have a preexisting psychiatric condition and those whose psychiatric problem emerged subsequent to the onset of heavy drinking."91 This distinction is important because in the latter group, many symptoms (especially anxiety and depression) clear within a month of cessation of drinking. Research has documented the rate and pattern of improvement: For those with a primary psychiatric disorder, improvement will be slower and will depend on effectively addressing this disorder.

There has been little research to determine the prevalence of dual diagnosis among women. The data that does exist indicate that dual diagnosis is prevalent in the total population. For example, the 1980-1982 National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-sponsored Epiderniologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey of more than 20,000 adults in five communities within the United States found that more than 34 percent of the respondents had experienced a form of mental illness or chemical dependency at some time during their lives.92 Approximately 23 percent of the respondents indicated a history of psychiatric problems, and 16 percent had a substance abuse disorder. These findings suggest that a significant number of those surveyed had two or more conditions. Approximately three out of ten individuals in the survey reporting a psychiatric illness were diagnosed as also having a substance abuse disorder at some time during their lives.93

Blume's 1990 discussion of Helzer's and Prybeck's analysis of the ECA concurs with Daley's findings and adds information specific to co-occurring disorders among women. According to Blume, "65 percent of female alcoholics, compared with 44 percent of males, had a second diagnosis."94 Thirty-one percent of the women with an alcohol diagnosis had drug abuse or dependence as a co- occurring disorder, while men with an alcohol diagnosis showed a 19 percent co-occurring drug dependency.95 Significantly, Blume also reports that not only were women with alcohol diagnoses more likely than men with alcohol diagnoses to have alcohol-related co-occurring disorders, but there were differences in the types of second diagnoses present. For women, major depression co-occurred in 19 percent (almost four times the rate for men); phobic disorder was diagnosed in 31 percent (more than twice the rate for men); and panic disorder occur-red in 7 percent of the women (three and one-half times the occurrences in men). In comparing the rates of mental disorders in women with alcohol-related diagnosis to women in the general population, the rates of these second diagnoses were considerably higher in the former group (e.g., the major depression rate was nearly triple that of the general female population, the rate for phobias was nearly double, and antisocial personality occurred in 10 percent of women with an alcohol-related diagnosis, which was an astounding 12 times higher than the rate in the general population of women).96

This section of the manual presents summary epidemiologic data on several groups of women: older women, pregnant and postpartum women, women in the criminal justice system, homeless women, lesbians, women with disabilities, African American women, American Indian women, Asian and Pacific Islander women, and Hispanic/Latina women. It should be noted that additional information relevant to these population groups is presented in chapters 4, 5, and 6.

In this manual, an "older" person is defined as a person 65 or older. Women in this age group who abuse substances have not been the subject of many research studies. The Food and Drug Administration has rarely included older women in studies evaluating medications, nor have drug companies included such women in their clinical trials,97 in spite of the increasing awareness of the problem of substance abuse among the elderly and the consequent health and socioeconomic problems.98

Older people are the most frequent users of prescription medications, accounting for approximately 25 percent of all prescriptions filled, although they comprise only 12 percent of the total U.S. population according to the 1990 census.99

The types of drugs that generate the most substance abuse problems in older people are analgesics and benzodiazepine tranquilizers, such as Valium, which usually are prescribed for conditions of chronic pain and/or chronic depression and anxiety. Slow metabolism of a psychoactive drug can lead to interactions with alcohol that can continue for several days after the most recent consumption of the drug. 100

Variations exist in prescribed drug use among racial/ethnic minority groups. For example, Hispanic women older than 60 years use Valium, Librium, and Tranxene more than do other women in this age group and use these drugs for longer periods and with greater frequency. However, African American women over 60 years of age report little use of psychotropic medications of any kind, in comparison with Caucasian and other women.101 Access to health care providers who may prescribe drugs is a possible factor in this difference.

| The alcohol-related cost of hospital care for elderly was estimated at $60 billion in 1990. |

An estimated 2.5 million older Americans have alcohol-related problems. Studies have shown that 21 percent of hospitalized patients over 60 who are hospitalized have a diagnosis of alcoholism. The alcohol-related cost of hospital care for the elderly was estimated at $60 billion in 1990. Of the 30,916 older Americans whose deaths in 1985 were attributed to alcohol abuse, each theoretically shortened her or his life by ten years. In addition to the loss in human terms, this translates into a productivity loss of $624 million. 102

Research consistently indicates that alcohol consumption decrease among persons in their 60s. However, this conclusion is largely based on cross-sectional studies that compare the drinking patterns of different age groups at a given point in time. This research method often does not account for the cultural and other influences on differences in drinking attitudes and behaviors that may be present within the various groups studied. It is possible that longitudinal and cohort analyses would result in different findings with respect to alcohol consumption patterns among older Americans. 103

Pregnant and postpartum women who use alcohol and other drugs are at risk for dangers to the fetus, HIV infection, STDs, forms of hepatitis, tuberculosis, deteriorating general health, and, in many cases, of becoming victims of violence. Specific adverse effects of maternal use of drugs during pregnancy place the fetus of the pregnant substance-abusing woman at risk for problems, including low birth weight, small head circumference, prematurity, and a variety of other medical and developmental complications. However, in the case of illegal drugs, evidence is not sufficiently broad or consistent to identify with certainty which drugs produce which effects at what levels. Nor is there evidence to untangle the environmental factors (such as poor nutrition, poverty, and lack of access to prenatal care) from substance abuse-related factors and focus on them as determinants of these problems.

More is known about the effects of alcohol consumption than about the effects of illegal drugs on pregnant women. Researchers have estimated that between 20 percent 104 and 73 percent 105 of women consume alcohol during pregnancy, although research indicates that there is no known safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy, or any "safe" period of gestation in which alcohol can be consumed.

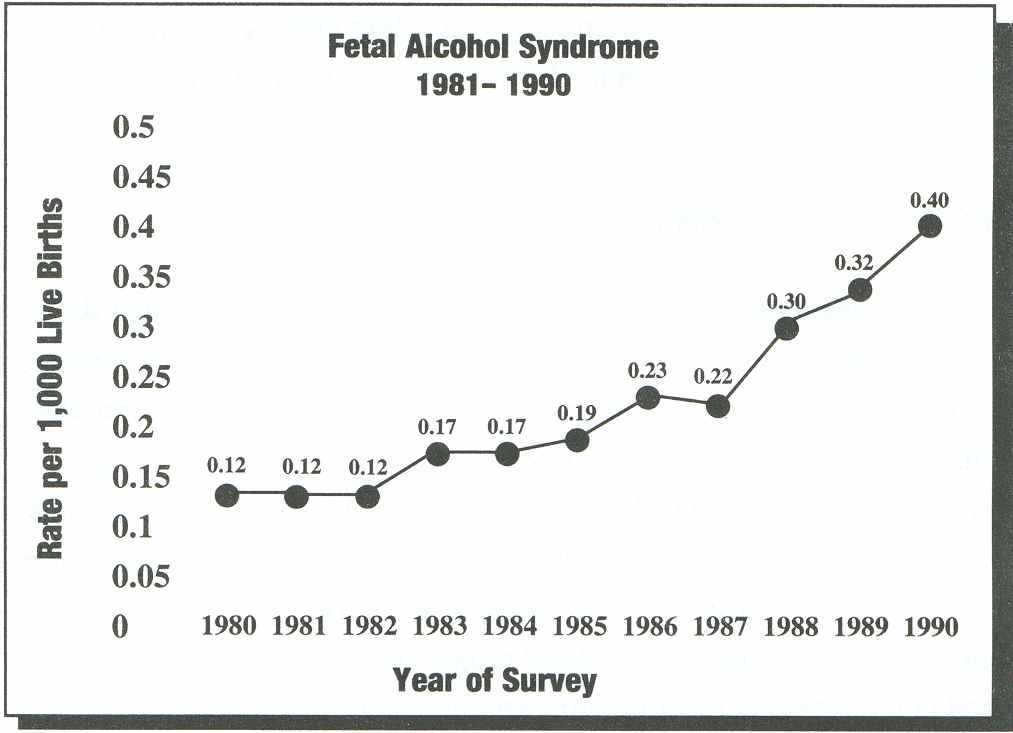

Alcohol abuse during pregnancy can produce a child with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) or Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE), or one with low birthweight, or physical, cognitive, or behavior disabilities. The rate of FAS was 0.40/1,000 live births in 1990, nearly four times the rate in 1980. Although the National Center for Health Statistics reports improved diagnostic and assessment techniques using the new FAS International Classifications of Diseases code for FAS, these new techniques alone would not account for the growth in the FAS rate, which more than doubled in the five-year period from 1985 to 1990 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Health United States 1991, 89.

Although biomedical scientists have linked alcohol use with gestational problems since at least 1899, FAS was not formally described until 1973. Clarren has summarized the clinical features of FAS:106

|

prenatal and postnatal growth deficiency; | |

|

central nervous system dysfunction; | |

|

a pattern of deformed facial characteristis; and | |

|

major organ system malformations. |

FAS, which is preventable, is now considered a leading cause of mental retardation in the United States.107 Not until 1991 was comprehensive data published concerning adolescent girls and adults with FAS, in spite of the increasing prevalence of FAS. In their report on 61 adolescent girls and adult women, Streissguth, et al., found that:

... although mental retardation is not necessarily predictable from the diagnoses alone, major psychosocial problems and life-long adjustment problems were characteristic .... The development and cognitive handicaps persist as long in life as these patients have been studied. None of these patients were known to be independent in terms of both housing and income .... Attentional deficits and problems with judgment, comprehension, and abstraction were the most frequently reported behavior problems .... Conduct problems, such as lying and defiance, also characterized a number of these patients. Data on trouble with the law and substance abuse were not systematically obtained .... ...108

| FAS, which is preventable, is now considered a leading cause of mental retardation in the United States. |

In another study of 92 adolescent girls and adult women with FAS, 36 percent of the patients reported having current or past experience with alcohol abuse, and 25 percent reported past abuse of other drugs.109 While no specific data are provided in the paper reporting this study, the authors indicate that "males abused alcohol at a higher rate than females." It is important for treatment program personnel to recognize that when adolescent girls and adult women with FAS present for treatment, they have particular issues that must be addressed by both medical and mental health personnel.

Use of cocaine, heroin, methadone, and other drugs during pregnancy is widespread, but experts know less about this type of abuse. However, some direct data are available concerning cocaine use during pregnancy. According to Clark and Weinstein, "reported prevalence of use [of cocaine] rates among pregnant women in large urban teaching hospitals range from 8 to 15 percent, although frequency of use during pregnancy varies considerably." 110 In 1992, according to the SAMHSA Household Survey, an estimated 329,000 women 18 to 34 (the age group with the highest birth rates) or 1 percent of respondents in this age group, had used cocaine in the previous month, and 87,000 had used crack.111 Data regarding women's use of heroin are not available by age group.

| Researchers estimate that each year 375,000 newborns are exposed perinatally to at least one illegal drug, with significant consequences. |

Only one national survey of prenatal exposure to illicit drugs has been conducted. According to that survey of 50 hospitals, an average of 11 percent of pregnant women were abusing illegal substances, with cocaine or crack as the drug of choice in 75 percent of the cases.112 Using these data, researchers estimate that each year 375,000 newborns are exposed perinatally to at least one illegal drug,113 with significant consequences. For example, low birthweight has been repeatedly associated with the use of heroin and methadone.114 Heroin has also been shown to produce severe ill effects in prenatally exposed children.

In an investigation of cocaine, Chasnoff, et al., found that the infants of cocaine-abusing mothers (with or without other drugs) had significantly lower birthweights, increased prematurity, and increased incidence of introuterine growth retardation (IUGR) and abruptio placentae than infants of non-drug using mothers.116 The findings of increased IUGR, prematurity, and low birthweight have been supported by other studies. 117 118

Although more studies of the epidemiology of drug abuse among pregnant women are clearly warranted, the growing evidence on adverse birth outcomes strongly suggests that illicit drug use contributes to high rates of infant mortality, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), and mental retardation. Anecdotal reports indicate that the problem may be getting worse, at least in some areas. In the District of Columbia, a sharp rise in infant mortality between 1987 and 1988-from. 19.6 to 23.2-has been attributed to increased crack use among pregnant women.119

In the past, women in the criminal justice system who had substance abuse problems received very little attention because their numbers were few and they typically served short sentences. In the last decade, however, the increased incarceration of women has shifted the focus to, at a minimum, understanding why more women are in the criminal justice system. Overall, the U.S. prison population has increased 250 percent since 1980 (from 329,821 in 1980 to 823,414 in 199 1). 120 As of the end of 1991, 47,691 of the total federal and state prisoners were women. 121 The growth in the rate of women in the prison population exceeded that of men in the prison population at the state level in the 1980s, increasing 202 percent for women as compared to 112 percent for men. 122

| The major reasons ,for the increase in incarceration of women have been the national crisis regarding alcohol and other drug problems. |

The major reasons for the increase in incarceration of women have been the national crisis regarding alcohol and other drug problems and the advent of mandatory minimum sentences for most drug offenses. In 1981, approximately 8 percent of state prisoners were serving sentences for drug offenses. By 1989, that number had increased to almost 30 percent. 123 Drug offenses at the federal level showed a similar increase during the 1980s, from 22 percent of all admissions to 55 percent. 124

The Bureau of Justice Statistics, in a 1989 survey of inmates in local jails, collected data from interviews in a nationally representative sample of 5,675 inmates in 424 jails, updating data from a similar survey conducted in 1983. 125 These data provide this profile of incarcerated women: In 1989, more than one in three female inmates were in jail for a drug offense, an increase from one in eight in 1983. Among all convicted female inmates, nearly 40 percent reported that they had committed their offense under the influence of drugs. More than half of convicted female inmates had used drugs in the month prior to the current offense, and approximately 40 percent had used drugs daily. These drugs included heroin, cocaine, or crack cocaine, LSD, PCP, and methadone. The percentage of women in jail who had used cocaine or crack cocaine in the month before their current offense more than doubled, from 15 percent in 1983 to 39 percent in 1989. The survey also found that about one in every three convicted women in jail reported they had committed their current offense for money to buy drugs. About one-fifth of all convicted women reported being under the influence of alcohol at the time of the offense, compared to more than 44 percent of convicted men.

Nearly two-thirds of the women in this study had grown up in a household with no parents or only one parent present: 40 percent in a single- parent household and 17 percent in a household without either parent. Almost one-third of all women in jail had a parent or guardian who had abused alcohol or other drugs. About 44 percent of the women reported that they had been either physically or sexually abused at some time in their lives before their current imprisonment.

In a 1992 study of major cities, the Sentencing Project showed that women's drug use is escalating, the severity of women's criminal activity is rising, and their recidivism rates are increasing. Women are being arrested at a much higher rate, and urinalysis testing indicates that their use of chemicals is increasing rapidly. Yet a very limited number of resources and comprehensive treatment efforts within the criminal justice system focus on women, most of whom are mothers, and their children. 126

| Homeless women represent a highly vulnerable group who engage in at-risk behaviors and develop health-related disorders at a rate greater than that of women in the general population. |

Homeless women represent a highly vulnerable group who engage in at- risk behaviors and develop health-related disorders at a rate greater than that of women in the general population. Their children often suffer from a wide range of medical problems, do poorly in school, manifest delays in cognitive and other development, and display behavioral or emotional problems. 127

Markers of the lifetime prevalence rates of alcohol abuse-related disorders among homeless women have ranged from 10 to 37 percent, with the most recent research indicating a 30 percent lifetime prevalence rate, compared with 5 percent for women in the general population. While alcohol problems are more common among homeless men than homeless women, this gender difference is far less than among men and women who are not homeless. 128

In contrast to homeless women who are not mothers, homeless mothers are much less likely to suffer from alcohol disorders (40 percent of homeless women without children versus 23 percent of homeless mothers). Homeless mothers are also less likely to be told that they have a drinking problem (31 percent versus 5 percent) than homeless women without children. Three studies have documented an approximate 8 to 10 percent lifetime prevalence rate of alcohol problems in homeless mothers, but the numbers are likely underestimated as are any estimates of health and other problems of the homeless. 129 Reports of lifetime prevalence of problems with drugs other than alcohol among homeless women have varied from 9 to 32 percent as compared to the lifetime rate of 5 percent in the general female population. By contrast, homeless mothers have an estimated lifetime 9 to 12 percent prevalence rate of substance abuse. Anecdotal reports from service providers suggest that growing numbers of homeless mothers are abusing not only alcohol but crack cocaine. 130

Adverse pregnancy outcomes (miscarriages, low birthweight, and infant mortality) are more likely in homeless women with substance abuse problems because they are usually poorly nourished and have limited access to prenatal health care and substance abuse treatment services. In one comparative study of homeless women in New York City, 39 percent of pregnant homeless women were found to have received no prenatal care, compared to only 14 percent of low-income women living in public housing communities, and 9 percent of the general population.131

While women who abuse alcohol and other drugs frequently experience depression and anxiety, homeless women are likely to exhibit more profound levels of these disorders. Unfortunately there are no recent data available on this subject.

According to Underhill's review of the limited research data available, an estimated 25 to 35 percent of lesbians have "serious problems with alcohol."132 A 1987 national survey of lesbians found that 16 percent of lesbians believed that they had a problem with alcohol, 14 percent used marijuana several times a week (33 percent used it several times a month), and 8 percent used stimulants in the past year. 133 These rates are much higher than for women as a whole. The results of the 1988 NIDA Household Survey found that 2 percent of female respondents used marijuana once a week or more, and 2.2 percent of female respondents engaged in nonmedical use of stimulants in the past year. 134 Lesbians also engage in polydrug use at high rates. Although the data are relatively old, a 1978 study found that 60 percent of lesbians used alcohol in combination with marijuana or amphetamines, hallucinogens, and barbiturates. 135 In spite of these relatively high rates of substance abuse, few treatment programs target lesbians or even have services that address their particular needs.

Lesbians experience most risk factors common to other women but also must cope with the effects of stigma, denial, alienation, self-doubt, guilt, and discrimination. These factors can take a heavy toll on the self-esteem of lesbians and make it difficult for them to meet their needs for affiliation. 136 The relative lack of treatment services responsive to the needs of lesbians and women in general is also a factor in the relatively high rates of alcoholism in this population. Not only are there few programs that conduct outreach to lesbians, few hold meetings or therapy sessions designed to meet their needs, and few have staff trained to address the needs of lesbians. 137

Although epidemiologic data are not available regarding substance abuse by adolescent lesbians, the recent report of the Department of Health and Human Services Secretary's Task Force on Youth Suicide indicates that lesbian adolescents begin to use drugs to reduce anxiety and pain when they become aware of their sexual orientation. Therefore, outreach, early intervention, and treatment are critical. 138

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the landmark civil rights act for people with disabilities, notes that 43 million Americans have some type of disability. 139 These include persons with physical health, sensory, learning, intellectual, or mental disabilities.

While data on the prevalence of alcohol and other drug problems among women with disabilities are lacking, the small body of research on disability and substance abuse suggests that people with disabilities use substances at the same or higher rates than those without disabilities.140 Women with disabilities face a similar set of risk factors as non-disabled women, including issues regarding body image, self-esteem, dependence, and sexual abuse, which in some instances are exacerbated by their disability status. 141 Another risk factor for women with disabilities is easy access to substances prescribed for pain or other aspects of the disability, as well as the compounding, often dangerous effects of prescription medication used in combination with alcohol and other drugs. 142

| African American women suffer disproportionately from the health consequences of alcoholism, including cancer, obstructive pulmonary disease, severe malnutrition, hypertension, and birth defects. |

In 1991, there were 15.8 million African American women in the United States: 6 percent of the total population. 143 As with other populations, alcohol is the most commonly abused substance among African American women and represents a health problem of significant proportions. According to a 1987 NIAAA report, African American women suffer disproportionately from the health consequences of alcoholism, including cancer, obstructive pulmonary disease, severe malnutrition, hypertension, and birth defects.144

Alcoholism was cited as a factor in the declining health status of African Americans in the 1991 report on the Health Status of Minority and Low Income Populations. 145 Death rates from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are twice as high for African Americans of both sexes as for Caucasians. Among women aged 15 to 34, cirrhosis rates for African American women are six times higher than those for Caucasian women, 146 and the risk of FAS is seven times higher for African American infants thanfor Caucasian infants. 147

The available data suggest that, while alcohol use begins later among African Americans than among Caucasians, the onset of alcohol-related problems appears earlier among African Americans.148 However, there are few differences in reported heavy alcohol use by African American and Caucasian women. In 1985, both groups of women were equally likely to be heavy drinkers (9 percent of respondents). In 1988, 7 percent of Caucasian women and 6 percent of African American women reported being heavy drinkers. 149

Patterns of drug use (other than alcohol) among African American women, as reflected in studies of women in treatment, indicate that they are more likely than other women in treatment to use opiates. A survey of treatment program data in 1980 showed that 70 percent of African Americans in treatment used opiates compared with 65 percent of Hispanics and 35 percent of Caucasians. African American women who use opiates enter treatment earlier than African American men and are more motivated by specific health problems. 150 In the past, African American women were less likely to engage in nonmedical use of psychotropic drugs than Caucasian or Hispanic women, but in 1992, according to the SAMHSA Survey, they were as likely to do so. African American women's reported use of cocaine in the previous month increased slightly between 1988 and 1992 (.5 percent to .6 percent of respondents), in contrast with Caucasian and Hispanic women whose reported use decreased (see Figure 6).

According to the 1990 census, there were 992,000 American Indian women in the United States.151 Alcoholism is the predominant health problem for American Indian women in what has been described as a "triad" that includes violence and depression. The rates of these problems have increased significantly for this population since 1970. 152 Fleming has reported that American Indian youth (including girls) "become involved with alcohol at an earlier age, consume alcohol more frequently and in greater quantities, and suffer greater negative consequences" than Caucasian women.153 Fleming also noted that, as of 1985, alcoholism was the fifth most frequent cause of death among American Indian women.154

| In all age groups, the alcohol-related mortality rates were significantly higher for American Indian women than for other women. |

In all age groups, the alcohol-related mortality rates were significantly higher for American Indian women than for other women; for example, for the age group 45 to 54, the rate for American Indian women was 48.3/1,000,000, while for women of all other races it was 8.4, and for all other races other than Caucasian it was 14.9.155 The FAS rate among American Indian populations is reportedly as high as 1 in 50, significantly higher than that of the general population of women. 156 As with Asian American women, data concerning use and abuse of other drugs are scarce, in part because the SAMHSA Survey and the NIDA-sponsored High School Survey do not present disaggregated data for this population. There is minimal data available on Alaskan Native women.

The term "Asian and Pacific Islanders" is often misunderstood as describing a homogeneous ethnic group. In reality, this label represents more than 60 different Asian and Pacific Islander groups, each with distinct cultural, language, and ethnic identities. Asian Americans have emigrated from countries and cultures as diverse as Japan, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Korea, India, and the Philippines. As of 1990, 3.7 million American women of Asian or Pacific Island origin-a 108 percent increase over the 1980 census-were American citizens.157

There have been only a few studies of alcohol and other drug use among Asian Americans and these studies have focused on Asian Americans in California and Hawaii.158 However, the prevalence of alcohol and drug use among Asian American women is believed to be relatively low,159 and to vary considerably by acculturation status. For example, the Institute of Medicine study of alcohol use found a strong influence of traditional cultures:

There is a significantly lower prevalence of alcohol use and abuse by females [among Asian American populations] until they acculturate over several generations. Even then, the prevalence rates may be lower than those found among Caucasian females. 160

The low prevalence of alcohol and other drug use by Asian Ame can women is related to strong cultural traditions, several of which were described by Sun in 1990:

|

the traditional emphasis on family versus individualism; | |

|

the more restrictive definition of the female role; and | |

|

the predominant belief systems--Confucianism and Taoism stress and advocate the concept of moderation. 161 |

For example, in a study of 125 female Koreans in Los Angeles, only one woman was classified as a heavy drinker, and 75 percent reported being abstainers. 162 However, as Sun notes, the low prevalence rates "could very well be due to the low reporting of alcohol and drug use or the low utilization of professional mental health and social services among Asian American women." 163 Moreover, the length of time that an individual Asian American has been in the U.S. and that there has been a wave of immigration from the country of origin, (e.g., Chinese vs. Cambodian patterns of immigration) has not been addressed in the research. Neither the NHSDA nor the NIDA-sponsored High School Survey- the two most important sources of national population data on alcohol and other drug use-present data for Asian American populations because the sample size was insufficient to do so.

Because most of the data regarding this ethnic group refers to "Hispanics" rather than Latinas, the former term is used in this chapter, which presents primarily epidemiological data. In the remainder of the manual, the term Hispanics/Latina is used to account for the full range of populations of Hispanic and Latin origin. As with other populations (including female Caucasians), it is important to note that:

... the population is not a unitary ethnic group. On the contrary, this group is quite heterogeneous, composed of "subgroups that vary by Latin American national origin, [race], generational status in the United States, and socio-economic level." The second is that, " although there are commonalities that have been well summarized in the literature ... many of these cultural attributes are continually undergoing modification as a result of acculturation." 164

Hispanic Americans are among the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States. From 1980 to 1990, their numbers increased 53 percent, compared to an increase of 9.8 percent for the rest of the population. 165 In 1990, just under 11 million Hispanic/Latina women lived in the United States, 4.4 percent of the total population.166 The largest defined subgroup of Americans is Mexican American (54 percent), and the second largest subgroup is Puerto Rican (35 percent).167 The total population of Hispanics/Latinas was 22 million or 9 percent of the total population. Importantly, the Hispanic/Latina population is one of the United States' youngest: 38.7 percent of this ethnic group were age 19 or under in 1990, compared with 26.7 percent of Caucasians and 32.2 percent of Asian Americans. Only American Indians in general were a younger population, with 39.3 percent 19 or younger. 168

According to data derived from the NHSDA, Hispanic Americans were slightly more likely to have reported the use of illicit drugs in the month before the survey than were Caucasian women (5.0 percent versus 4.7 percent). They were much more likely to have used cocaine specifically (1.2 percent versus 0.4 percent). However, Hispanic women were less likely to have consumed alcohol once a week or more than were their Caucasian counterparts: 9.2 percent versus 14.4 percent. 169 Reported use of inhalants by Hispanic/Latina women increased from .3 percent of respondents in 1988 to .5 percent in 1992, from an estimated 25,000 to 39,000. The increase for Caucasian women was smaller (.2 percent to .3 percent). 170

Although Hispanic women do not have the same disproportionately high rates of infant mortality or low birthweight babies as African American and American Indian women, they do have high rates of diabetes. This condition, which is also a complicating factor with alcohol abuse, contributes to infant morbidity, including developmental disabilities.

| Although Hispanic women do not have the same disproportionately high rates of infant mortality or low birthweight babies as African American and American Indian women, they do have high rates of diabetes. |

According to the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP), there are important differences among Hispanic American adolescents by subgroup. Although these data are not disaggregated by gender, they are important to consider in the treatment of adolescent Hispanic girls. "In the NHSDA [National Household Survey on Drug Abuse] data, Hispanics/ Latinos in this [12 - 17] age bracket had rates of lifetime use of cocaine higher than those for white or Blacks; these rates were highest among Puerto Ricans and Cubans, while Mexican Americans' use rate was lower than all other groups. Regarding marijuana use, Mexican Americans had higher rates than Puerto Ricans; in comparing Hispanic- subHANES (Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) to NHSDA data specifically on marijuana use, it appears that the rate for Mexican Americans surpasses that for non-whites." 171

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (1993). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992. Rockville, MD, 10.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (1993). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Preliminary Estimates 1992. Rockville, MD, 19.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 55.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 31.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 37.

National Center for Health Statistics. (1993). Health United States: 1992. Hyattsville, Maryland: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 46.

Health United States: 1992, 50-5 1.

Calculated based on data derived from: Health United States: 1992, 21and 314.

Health United States: 1992, 92.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (1993). Estimates from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN): 1992 Estimates of Drug-related Emergency Room Episodes; Advanced Report # 4. Rockville, MD.

ibid.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Preliminary Estimates 1992,9.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1993). Eighth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, 9.

Calculated based on Eighth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health, 9 and population data derived from: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census. (1991) Statistical Abstract of the United States 1992, 18.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1993). Eighth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, 17.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. (1990). Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health from the Secretary of Health and Human Services, January, 1990. Rockville, MD: Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration, xxi.

ibid.

Calculated based on data derived from National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Preliminary Estimates 1992, 10, and National Household Survey: Population Estimates 1992, 13.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,121.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,19.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 122-123.

See for example Ross, H. E. (1989). Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Treated Alcoholics: A Comparison of Men and Women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 13 (6), 815.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,19.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,25.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,31.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,37.

Estimates from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN): 1992 Estimates of Drug-related Emergency Room Episodes.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 104.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 104.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992, 55.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (1989). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1988. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 53.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,55.

Matteo, S. (1988). The Risk of Multiple Addictions: Guidelines for Assessing a Woman's Alcohol and Drug Use. The Western Journal of Medicine (149), 742.

Roth, P., Ed. (199 1). The Model Program Guide. Alcohol and Drugs are Women's Issues, Volumes I and 11. Metuchen: NJ: The Scarecrow Press, ix.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (1992). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1990. Rockville, MD, 129.

Ross, H.E., 814.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (1992). National Drug Control Strategy: A Nation Responds to Drug Use. Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office, 58.

Institute of Medicine. (1990). The Treatment of Special Populations: Overview and Definitions. In Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press, 352.

Institute of Medicine. (1990). Populations Defined by Structural Characteristics. In Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems, 356.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1992). State Resources and Services Related to Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Problems. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 31-32.

ibid.

Bigel Institute for Health Policy. (1992). Drug Services Research Survey: Phase 11, Final Report. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, Table 20.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (1992). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1991. Rockville, MD, 104.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1991,55.

The MayaTech Corporation. (1990). Evaluation of the Health Care Financing Administration's Alcohol Services Demonstration: The Medicare Experience. Silver Spring, MD: The MayaTech Corporation, 52.

General Services Branch of Alcoholics Anonymous. (1993). 1992 Membership Survey. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous, Inc.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,19.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,55.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Preliminary Estimates 1992,10.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,19.

Migram, G.G. (1990). Adolescent Women. In Engs, R. C., Ed. Women: Alcohol and Other Drugs. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Health United States: 1991, 207.

Department of Health and Human Services. (1993). National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975-1992. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 12.

Galbraith, S. (1991). Women and Legal Drugs. In Roth, P., Ed. Alcohol and Drugs are Women's Issues; Volume 1: A Review of the Issues. Metuchen, N. J.: Scarecrow Press, 150.

Matteo, S., 742.

Moise, R., Kovach, J., Reed, B., and Bellows, N. (1982). A Comparison of Blackand White Women Entering Drug Abuse Treatment Programs. The International Journal of Addictions, 17(l), 46-47.

Matteo, S., 742.

Health United States: 1992, 56.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health from the Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 114.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 116.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 117.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 121.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 124.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 116.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 117.

Seventh Special Report to the U.S. Congress, 123.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Screening for Infectious Diseases Among Substance Abusers. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Rockville, MD, 2.

ibid.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, 140.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 146.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 166-167.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 178.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 178.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 178.

Centers for Disease Control. (1993). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 1992. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 178.

Schultz, S., Zweis, M., Sing, T., and Hgoos, M. (1990). Congenital Syphilis: New York City 1968-1988. American Journal of Diseases of Children (144), 279.

Centers for Disease Control. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Nov 19, 1993, 42(45), 870.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1993). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Atlanta, GA: Public Health Service. March, 1993, 9.

ibid.

ibid.

McArthur, L. (1991). Women and AIDS. In Roth, P., Ed., Alcohol and Drugs Are Women's Issues, Volume 1: A Review of the Issues. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 114-119.

HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 1993, 9.

Trapido, E., Lewis, N., and Comeford, M. (1990). HIV- I and AIDS in Belle Glade, Florida: A Re-examination of the Issues. American Behavioral Scientist (33), 451-64.

Inciardi, J., Lockwood, D., and Pottieger, A. (199 1). Crack Dependent Women and Sexuality: Implications for STD Acquisition and Transmission. Addiction and Recovery (11) 4, 25-28.

Sterk, C. and Elifson, K. (1990). Drug-related Violence and Street Prostitution. In De La Rosa, M., Lambert, E., and Gropper, B., Eds., Drugs and Violence: Causes, Correlates, and Consequences: NIDA Research Monograph (103). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 172 1.

Center for Disease Control. (1994). Unpublished Data. Atlanta, GA.

Centers for Disease Control. (1994). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Atlanta, GA: Public Health Service. May 27, 1994,43(20).

Mondanaro, J. (1989). Chemically Dependent Women: Assessment and Treatment. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 114.

Institute of Medicine. (1990). Populations Defined by Functional Characteristics. In Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems, 385.

Institute of Medicine, 386.

Daley, D.C., Moss, H.B., and Campbell, F. (1993). Dual Disorders: Counseling Clients with Chemical Dependency and Mental Illness. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 1-4.

ibid.

Blume, S. (1990). Alcohol and Drug Problems in Women: Old Attitudes, New Knowledge. In Mikman, H.B. and L.I. Sederer, Eds., Treatment Choices for Alcoholism and Substance Abuse. New York: Lexington Books, 191. (8 1).

ibid.

ibid.

Bernstein, L., Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. (1989). Characterization of the Use and Misuse of Medications by the Elderly Ambulatory Population. Medical Care 27(6), 654-663:

Among the consequences of psychotherapeutic drug abuse are suicide, compulsive use, overdose, affective and sleep disturbances, depression, and cognitive and motor impairment. See The Risk of Multiple Addictions: Guidelines for Assessing a Woman's Alcohol and Drug Use, 741-745.

Abrams, R., and Alexsopoulues, G. (1987). Substance Abuse in The Elderly: Alcohol and Prescription Drugs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry (38)12, 1286.

Morse, R. (1988). Substance Abuse Among the Elderly. Bulletin of the Menniger Clinic (52), 259-68.

The Risk of Multiple Addictions: Guidelines for Assessing a Woman's Alcohol and Drug Use, 741-745.

Select Committee on Aging, House of Representatives. (1992). Alcohol Abuse and Misuse Among the Elderly. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1993). Eighth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health from the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services. 20.

Serdula, M., Williamson, D.F., Kendrick, J.S., Anda, R.F., and Byers, T.(1991). Trends in Alcohol Consumption by Pregnant Women: 1985 through 1988. Journal of the American Medical Association 265(7): 876-879.

Gomby, D.S., and Shino, P.H. (1991). Estimating the number of substance-exposed infants. In Behreman R.E., Ed., The Future of Children: Drug Exposed Infant, l(l), 36-49.

Clarren, S.K. (1981). Recognition of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association 245 (23), 2436-2439.

Streissguth, A.P., et al. (1991). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Adolescents and Adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. (265)15, 1961-1967.

ibid.

LaDue, R.A., Streissguth, A.P., and Randels, S.P. (1992). Clinical Considerations Pertaining to Adolescents and Adults with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. In Sonderegger, T., Ed., Perinatal Substance Abuse: Research Findings and Clinical Implications., Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press, 116.

Clark, H.W., and Weinstein, M. (1993). Chemical Dependency. In Paul, M., Ed., Occupational and Environmental Hazards: A Guide for Clinicians. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wikins, 350.

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1992,31,37.

Chasnoff, I.J. (1989). Drug Use and Women: Establishing a Standard of Care. New York Academy of Science (562), 208-210.

National Association of Perinatal Addiction Research and Education. News release. 8 Aug., 1988, Chicago, IL.

Zuckerman, B. (1985). Developmental Consequences of Maternal Drug Use During Pregnancy. In Pinkert T.M., Ed., and Hutchings, D.E.(1985). Prenatal Opioid Exposure and the Problem of Causal Inference.Current Research on Consequences of Maternal Drug Abuse: NIDA Research Monograph (59). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Householder, J., et a]. (1982). "Infants Born to Narcotic-Addicted Mothers." Psychology Bulletin (2)2, 453-68, and Hutchings, D.E. Prenatal Opioid Exposure and the Problem of Causal Reference. In Pinkert, T.M., Eds., Current Research on the Consequences of Maternal Drug Abuse: NIDA Research Monograph (59).