5.

Medical Care for Obese Patients: Advice for Health Care Professionals

More than 60 percent of adults in the United States are overweight or obese, and obese persons are more likely to be ill than those who are not. Obesity presents challenges to physicians and patients and also has a negative impact on health status. Some patients who are obese may delay medical care because of concerns about disparagement by physicians and health care staff, or fear of being weighed. Simple accommodations, such as providing large-sized examination gowns and armless chairs, as well as weighing patients in a private area, may make the medical setting more accessible and more comfortable for obese patients. Extremely obese patients often have special health needs, such as lower extremity edema or respiratory insufficiency that require targeted evaluation and treatment. Although physical examination may be more difficult in obese patients, their disproportionate risk for some illnesses that are amenable to early detection increases the priority for preventive evaluations. Physicians can encourage improvements in healthy behaviors, regardless of the patient's desire for, or success with, weight loss treatment. (Am Fam Physician 2002;65:81-8. Copyright© 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

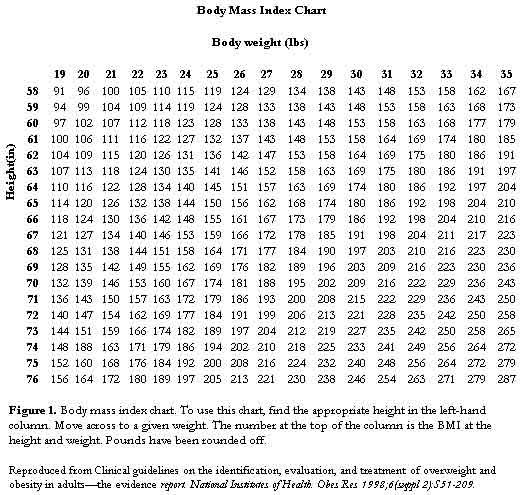

The percentage of adults in the United States considered to be overweight or obese has increased to more than 60 percent.1 Clinical guidelines from the National Institutes of Health2 define overweight as a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 kg per m2, while obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 kg per m2 or more (Table 1).2 Of special concern is the dramatic increase from approximately 15 to 27 percent in the category of obesity during the past two decades.1 BMI correlates significantly with total body fat content.2 It is calculated by dividing weight (in kg) by height (in m2) or, alternatively, by dividing weight (in lb) by height (in inches2) and multiplying by 703. Figure 12 provides a chart to calculate BMI, and a BMI calculator is available online at: http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/.

Obesity disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minority populations, especially women. For example, 10.3 percent of African American women are extremely obese (defined as a BMI of 40 kg per m2 or more), compared with 6.2 percent of non-Hispanic white women.3 Based on the high prevalence rates of obesity in all population groups, virtually every physician can expect to provide medical care for patients who are obese. Overweight and obesity confer increased health risks to numerous organ systems, and the risk of developing obesity-related disease is affected by the degree of overweight and the distribution of body fat.4 It is also possible that at least some of the health problems experienced by persons who are obese are worsened by lack of access to care because of their obesity.

Results from several studies5-7 suggest that patients who are obese are less likely to receive certain preventive care services, such as pelvic examinations, Papanicolaou (Pap) smears, and physician breast examinations, than those who are not obese. It is unclear whether this is a result of patient or physician factors. For example, physicians may be less likely to perform pelvic examinations on patients who are obese, because of the difficulty in performing an adequate examination.7 In addition, the greater likelihood of concomitant health problems in obese patients, such as diabetes or hypertension, may decrease the time available during the medical visit for attention to preventive care.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patient concerns about being disparaged by physicians and/or medical staff because of their weight may also be an issue in the lack of preventive services for obese patients, because this fear may decrease patients' willingness to seek medical care. Obese patients, particularly those considered to be extremely obese, have reported being treated with disrespect by physicians and other medical staff.8,9 Even among less severely obese women participating in weight loss trials whose mean BMI of 35.2 was less than the mean BMI in some previous studies, 13.2 percent reported that physicians said critical or insulting things about their weight at least sometimes, and 22.5 percent reported that they were at least sometimes treated with disrespect because of their weight.10

Results of a recent study11 about family physician attitudes regarding patients who are obese indicate that 38.5 percent attributed lack of willpower as one of the most significant contributors to their patients' obesity. It is not surprising, therefore, that 12.7 percent of women in one study5 reported delaying or canceling a physician appointment because of their weight concerns. Concern about negative attitudes of the health care staff may be a particular impediment to examinations (e.g., breast examination) that involve disrobing and direct patient contact. Reluctance to seek care may also arise from patients' self-consciousness about their obesity, or concerns about having gained weight or not having lost weight since a previous visit.

Physicians should address obesity as an independent health risk. Guidelines from the National Institutes of Health2 on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of adult obesity provide evidence-based guidance. Nonetheless, physicians may also need guidance on addressing the special health care needs of patients who are overweight or obese. The purpose of this article is to provide guidance on ways to optimize the medical care of these patients, independent of recommendations for weight loss treatment.

Access to Care

To provide the best possible medical care for patients who are overweight or obese, it is helpful to create an office environment that is accessible and comfortable for these patients. This includes educating staff about being respectful to patients regardless of body weight or size, and having appropriate equipment and supplies available (Table 2).12,13

Physical setting

It is useful to have one or two sturdy, armless chairs and/or firm and high sofas ("high" meaning not low to the ground) in the waiting room, not only for those patients who are extremely obese, but also for older patients who have difficulty with mobility. Wide examination tables, bolted to the floor or wall (if possible), ensure that the table does not tip over when the patient sits on one end.

Appropriate-sized examination gowns can also make patients feel more comfortable and are available through many suppliers. A sample listing of catalogs with medical supplies and equipment is provided. Other easily obtained and useful equipment includes large tourniquets, longer needles for phlebotomy, oversized vaginal speculae and a split toilet seat for urine collection.

Accurate measurement of blood pressure requires special consideration. A standardized blood pressure cuff should not be used on persons with an upper-arm circumference of more than 34 cm. Large arm cuffs or thigh cuffs can aid in an accurate determination of blood pressure. If the upper arm circumference exceeds 50 cm, the American Heart Association14 recommendations suggest using a cuff on the forearm and feeling for the appearance of the radial pulse at the wrist to estimate systolic blood pressure. The recommendations note that the accuracy of forearm measurement has not been validated.14

|

||

| Information from National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance. Guidelines for health care providers in dealing with fat patients. Retrieved September 2001, from: http://www.naafa.org/documents/brochures/healthguides.html, and Health and weight at Kaiser Permanente: practice recommendations, 1999. Oakland, Calif., Kaiser Permanente Regional Health Education. Pamphlet. |

Weighing Patients

Weighing patients who are overweight and obese demands particular sensitivity. Some patients report avoiding medical care because of fears of being weighed and because of their concerns about negative comments that are sometimes made.9 In addition, standard office scales (which often have a maximum weight of 300 lb) may preclude obtaining accurate weights for those patients who exceed 300 lb. Office scales that can weigh patients of 500 lb or more are readily available.

Physicians may also wish to discuss the patient's feelings about the measurement of weight, and it may be preferable to negotiate how often an accurate weight should be obtained for the patient's medical care. It may not be necessary to obtain a weight measurement, for example, on a patient presenting for evaluation and treatment of a sore throat. If the physician believes that the patient's condition is caused or exacerbated by weight, the physician should ask the patient if he or she would like to discuss weight.15

Sensitivity in word choice may also be helpful. Patients may respond extremely negatively to use of the term obesity, but be more amenable to discussion of their difficulties with weight or being overweight. When weighing is appropriate, it is helpful to do so in a private area (if the scale is in a hallway, a screen or curtain can be used) and to record the weight without comment.12

Special Health Needs of Patients Who Are Extremely Obese

The barriers and limitations in access to care experienced by persons who are extremely obese are unfortunately present in the context of the greater need for health care. Evidence indicates that persons with a BMI of 40 or more have a substantially increased risk for death, and not uncommonly, are not only at risk for illness but are already ill.2

The array of diseases affected by excess body weight is large and is addressed in detail in another report.4 For example, there is a relationship between increased body weight and the development of diabetes, degenerative joint disease and sleep apnea, but this relationship is even more pronounced as the level of obesity increases. The relationship between extreme obesity and diabetes is especially strong. Results of studies have determined the excess risk of diabetes associated with a BMI of more than 35 to be between eight to 30 times that of persons of normal weight.2 Consequent to the increased medical risks and problems associated with extreme obesity, it is especially important that obesity-related risk factors be monitored in these patients.16,17 Table 32,16-18 describes some of the medical conditions for which patients, in any of the three categories of obesity, are at increased risk, along with suggested monitoring.

Elevated risks of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and ischemic heart disease lead to the need for regular monitoring for hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, as well as a need to carefully assess symptoms of coronary ischemia. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is also more common in patients who are obese, especially those with insulin resistance, and may lead to eventual hepatic fibrosis.18

Some additional medical conditions are particularly associated with extreme obesity and may go unrecognized in the clinic. These conditions include lower extremity edema, thromboembolic disease, sleep apnea, and a particular form of respiratory insufficiency known as Pickwickian syndrome.19-24 Clinical presentations of dyspnea and edema in extremely obese patients may be incorrectly assumed to be caused by underlying ischemic damage of the left heart. Although ischemic heart disease does occur with greater frequency in obese persons, dyspnea and edema are common in extremely obese patients even among those without left heart ischemic damage, and may have other underlying causes.2 Respiratory conditions associated with extreme obesity, such as sleep apnea and Pickwickian hypoventilation, also predispose to right-sided heart failure because of elevated pulmonary arterial bed pressures.4 Echocardiography may be useful for evaluating cardiac structure and function in symptomatic patients in whom obesity makes examination difficult.

Shortness of breath or sleep disturbance, for example, may be attributed to the patient's excessive body weight. However, further medical evaluation may point to medical conditions, such as sleep apnea, which, while related to obesity, can be ameliorated even in patients who are unable to lose weight. In addition to potentially life-threatening conditions, extremely obese patients may be troubled by conditions associated with skin compression, such as intertrigo and venous stasis ulcers. Patients who have diabetes are at special risk for fungal infections. Attention to foot care is also important for the extremely obese patient who may have difficulties with reach. Referral to a podiatrist may be indicated in some obese patients and is especially important for those with diabetes.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Improving Health in the Absence of Weight Loss Treatment

Although weight loss should be discussed as a potential treatment for weight-related medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, osteoarthritis), treatment of obesity related risk factors or illnesses—even in the absence of weight loss—is important because not all patients are able or willing to attempt weight loss. Among these patients, physicians can always encourage avoidance of further weight gain. Such a strategy can limit the accumulation of additional medical risks associated with increased weight gain. Health-related behaviors, such as healthful eating and physical activity, can be highlighted as a means to improve health, independent of weight loss.

Fitness may ameliorate many of the cardiovascular health risks associated with overweight and obesity.25,26 Although obese patients may be reluctant to engage in physical activity because

of discomfort or embarrassment, physicians can encourage slow, gradual increases in physical activity (e.g., walking with a friend for 10 minutes a day, parking the car farther away in the parking lot). A brochure entitled "Active at Any Size," written for very large persons and containing tips for becoming more active, is available from the Weight-Control Information Network at 1-877-946-4627 or e-mail:

win@info.niddk.nih.gov.

Preventive Care and Health CounselingBecause obese patients frequently have associated health problems and are likely to be seen for ongoing treatment of these illnesses, physicians may be less likely to think about and to recommend preventive care. It is also true that barriers exist to adequate physical examination in extremely obese patients, and that adequate palpation of abdominal and pelvic organs may be difficult, if not impossible, in some patients. Research is needed to determine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of alternative means for detecting conditions not amenable to physical examination because of a patient's body habitus. However, recommended preventive evaluations, including Pap smear, physician breast examination and mammography in women, |

|

prostate examination in men and stool testing for occult blood can be performed in patients of all sizes. The realization that obese patients suffer disproportionately from some illnesses that are amenable to early detection should increase the priority for performing preventive evaluations and for sensitively addressing concerns with patients who may initially be reluctant to undergo appropriate testing.

Enhancing Self-Acceptance

Issues of self-esteem and self-acceptance are of particular importance to obese patients. Physicians may be concerned that encouraging self-acceptance in obese patients will undermine efforts aimed at producing weight loss that can significantly improve health. Self acceptance, however, need not imply complacency or the failure to heed well-founded advice about reducing the health risks of obesity. Conflict need not exist between greater self-acceptance and efforts to make necessary dietary and exercise changes. A more constructive view is to focus on promoting self acceptance and lifestyle changes aimed at improving health behaviors.

Encouraging patients to lead as full and active a life as possible, regardless of their body weight or success at weight control, may help patients make positive changes such as increasing physical activity.27 Some obese patients find support groups helpful for increasing self-esteem and enhancing commitment to a healthier lifestyle.

Members of the National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity:

Charles J. Billington, M.D., Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minn.; Leonard H. Epstein, Ph.D., State University of New York at Buffalo; Norma J. Goodwin, M.D., Health Watch Information and Promotion Service, New York City; Rudolph L. Leibel, M.D., Columbia University, New York City; F. Xavier Pi-Sunyer, M.D., St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, Columbia University, New York City; Walter Pories, M.D., East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.; Judith S. Stern, Sc.D., R.D., University of California at Davis; Thomas A. Wadden, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Roland L. Weinsier, M.D., Dr.P.H., University of Alabama at Birmingham; G. Terence Wilson, Ph.D., State University of New Jersey, Rutgers; and Rena R. Wing, Ph.D., Brown University, Providence, R.I. National Institutes of Health staff: Susan Z. Yanovski, M.D.; Van S. Hubbard, M.D., Ph.D.; Jay H. Hoofnagle, M.D., Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition, Bethesda, Md.

Please address correspondence to Susan Z. Yanovski, M.D., NIDDK, 2 Democracy Plaza, Room 665, 6707 Democracy Blvd., Bethesda, MD 20892-5450 (e-mail: sy29f@nih.gov). Reprints are not available from the authors.

Drs. Hill, Wadden, and Wilson serve as consultants and/or are on the speakers bureaus of Knoll Pharmaceutical Company and Roche Laboratories, and Dr. Wadden has received research project support from Knoll Pharmaceutical Company, Roche Laboratories, and Novartis Nutrition. Drs. Weinsier and Stern are members of the Weight Watchers Scientific Advisory Board. Dr. Wing receives research project support from Roche Laboratories. Dr. Rolls has served as consultant to and/or received research project support from Amgen, Knoll Pharmaceutical Company, Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Procter & Gamble, and Ross Products/Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Pi-Sunyer has consulted for and/or received research project support from Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Roche Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Amgen, Genentech, and Parke-Davis. Dr. Billington has consulted for Procter & Gamble and Entelos.

The authors thank Ms. Lynn McAfee, Council on Size and Weight Discrimination, for her thoughtful comments.

REFERENCES

- National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults: United States, 1999. Retrieved September 2001, from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/ hestats/obese/obse99.htm.

- Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998;6(suppl 2):S51-209.

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22:39-47.

- National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:898-904.

- Olson CL, Schumaker HD, Yawn BP. Overweight women delay medical care. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3:888-92.

- Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Screening for cervical and breast cancer: is obesity an unrecognized barrier to preventive care? Ann Intern Med 2000;132:697-704.

- Adams CH, Smith NJ, Wilbur DC, Grady KE. The relationship of obesity to the frequency of pelvic examinations: do physician and patient attitudes make a difference? Women Health 1993;20:45-57.

- Fontaine KR, Faith MS, Allison DB, Cheskin LJ. Body weight and health care among women in the general population. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:381-4.

- McAfee L. Discrimination in medical care. In: Healthy weight journal: research, news and commentary across the weight spectrum. Hettinger, N.D.: Healthy Living Institute, 2000;11:96-7.

- Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, Bennett A, Steinberg C, Sarwer DB. Obese women's perceptions of their physicians' weight management attitudes and practices. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:854-60.

- Harris JE, Hamaday V, Mochan E. Osteopathic family physicians' attitudes, knowledge, and self reported practices regarding obesity. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1999;99:358-65.

- National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance. Guidelines for health care providers in dealing with fat patients. Retrieved September 2001, from: http://www.naafa.org/documents/brochures/healt hguides.html.

- Health and weight at Kaiser Permanente: practice recommendations, 1999. Oakland, Calif., Kaiser Permanente Regional Health Education. Pamphlet.

- Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation 1993;88(5 pt 1):2460-70.

- Stunkard AJ. Talking with patients. In: Stunkard AJ, Wadden TA, eds. Obesity: theory and therapy. 2d ed. New York: Raven Press, 1993.

- Kushner RF, Weinsier RL. Evaluation of the obese patient. Practical considerations. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:387-99.

- Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, Herman WH. Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:1563-80.

- Falck-Ytter Y, Younossi ZM, Marchesini G, McCullough AJ. Clinical features and natural history of nonalcoholic steatosis syndromes. Semin Liver Dis 2001;21:17-26.

- Blankfield RP, Hudgel DW, Tapolyai AA, Zyzanski SJ. Bilateral leg edema, obesity, pulmonary hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2357-62.

- Valensi P, L'Hermite F, Behar A, Sandre-Banon D, Cohen-Boulakia F, Attali JR. Extra cellular water and increase in capillary permeability to albumin in overweight women with swelling syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:126-30.

- Davidson BL. Applying risk assessment models in non-surgical patients: overview of our clinical experience. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1999;10(suppl 2):S85-9.

- Hansson PO, Eriksson H, Welin L, Svardsudd K, Wilhelmsen L. Smoking and abdominal obesity: risk factors for venous thromboembolism among middle-aged men: "the study of men born in 1913". Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1886-90.

- Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Hopper K, Lotsikas A, Lin HM, et al. Sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness and fatigue: relation to visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercytokinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:1151-8.

- Anstead M, Phillips B. The spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing. Respir Care Clin North Am 1999; 5:363-77.

- Blair SN, Brodney S. Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31(11 suppl):S646-62.

- Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:373-80.

- Wilson GT. Acceptance and change in the treatment of eating disorders and obesity. Behavior Therapy 1996;27:417-39.

Copyright 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians.

Am Fam Physician 2002; 65: 81-8.

Reprinted with permission.