| Contents | Previous | Next |

Stacked on top of one another in the spine are more than 30 bones, the vertebrae, which together form the spine. They are divided into four regions:

The vertebrae are linked by ligaments, tendons, and muscles. Back pain can occur when, for example, someone lifts something too heavy, causing a sprain, pull, strain, or spasm in one of these muscles or ligaments in the back.

Between the vertebrae are round, spongy pads of cartilage called discs that act much like shock absorbers. In many cases, degeneration or pressure from overexertion can cause a disc to shift or protrude and bulge, causing pressure on a nerve and resultant pain. When this happens, the condition is called a slipped, bulging, herniated, or ruptured disc, and it sometimes results in permanent nerve damage.

The column-like spinal cord is divided into segments similar to the corresponding verte- brae: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. The cord also has nerve roots and rootlets which form branch-like appendages leading from its ventral side (that is, the front of the body) and from its dorsal side (that is, the back of the body). Along the dorsal root are the cells of the dorsal root ganglia, which are critical in the transmission of “pain” messages from the cord to the brain. It is here where injury, damage, and trauma become pain.

The central nervous system (CNS) refers to the brain and spinal cord together. The peripheral nervous system refers to the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral nerve trunks leading away from the spine to the limbs. Messages related to function (such as movement) or dysfunction (such as pain) travel from the brain to the spinal cord and from there to other regions in the body and back to the brain again. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary functions in the body, like perspiration, blood pressure, heart rate, or heart beat. It is divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems have links to important organs and systems in the body; for example, the sympathetic nervous system controls the heart, blood vessels, and respiratory system, while the parasympathetic nervous system controls our ability to sleep, eat, and digest food.

The peripheral nervous system also includes 12 pairs of cranial nerves located on the underside of the brain. Most relay messages of a sensory nature. They include the olfactory (I), optic (II), oculomotor (III), trochlear (IV), trigeminal (V), abducens (VI), facial (VII), vestibulocochlear (VIII), glossopharyngeal (IX), vagus (X), accessory (XI), and hypoglossal (XII) nerves. Neuralgia, as in trigeminal neuralgia, is a term that refers to pain that arises from abnormal activity of a nerve trunk or its branches. The type and severity of pain as- sociated with neuralgia vary widely.

Sometimes, when a limb is removed during an amputation, an individual will continue to have an internal sense of the lost limb. This phenomenon is known as phantom limb and ac- counts describing it date back to the 1800s. Similarly, many amputees are frequently aware of severe pain in the absent limb. Their pain is real and is often accompanied by other health problems, such as depression.

What causes this phenomenon? Scientists believe that following amputation, nerve cells “rewire” themselves and continue to receive messages, resulting in a remapping of the brain’s circuitry. The brain’s ability to restructure itself, to change and adapt following injury, is called plasticity (see section on Plasticity).

Our understanding of phantom pain has improved tremendously in recent years. Investigators previously believed that brain cells affected by amputation simply died off. They attributed sensations of pain at the site of the amputation to irritation of nerves located near the limb stump. Now, using imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), scientists can actually visualize increased activity in the brain’s cortex when an individual feels phantom pain. When study participants move the stump of an amputated limb, neurons in the brain remain dynamic and excitable. Surprisingly, the brain’s cells can be stimulated by other body parts, often those located closest to the missing limb.

Treatments for phantom pain may include analgesics, anticonvulsants, and other types of drugs; nerve blocks; electrical stimulation; psychological counseling, biofeedback, hypnosis, and acupuncture; and, in rare instances, surgery.

The hot feeling, red face, and watery eyes you experience when you bite into a red chili pep- per may make you reach for a cold drink, but that reaction has also given scientists important information about pain. The chemical found in chili peppers that causes those feelings is capsaicin (pronounced cap-SAY-sin), and it works its unique magic by grabbing onto receptors scattered along the surface of sensitive nerve cells in the mouth.

In 1997, scientists at the University of California at San Francisco discovered a gene for a capsaicin receptor, called the vanilloid receptor. Once in contact with capsaicin, vanilloid receptors open and pain signals are sent from the peripheral nociceptor and through central nervous system circuits to the brain. Investigators have also learned that this receptor plays a role in the burning type of pain commonly associated with heat, such as the kind you experience when you touch your finger to a hot stove. The vanilloid receptor functions as a sort of “ouch gateway,” enabling us to detect burning hot pain, whether it originates from a 3-alarm habanera chili or from a stove burner.

Capsaicin is currently available as a prescription or over-the-counter cream for the treatment of a number of pain conditions, such as shingles. It works by reducing the amount of substance P found in nerve endings and interferes with the transmission of pain signals to the brain. Individuals can become desensitized to the compound, however, perhaps be- cause of long-term damage to nerve tissue. Some individuals find the burning sensation they experience when using capsaicin cream to be intolerable, especially when they are already suffering from a painful condition, such as postherpetic neuralgia. Soon, however, better treatments that relieve pain by blocking vanilloid receptors may arrive in drugstores.

As a painkiller, marijuana or, by its Latin name, cannabis, continues to remain highly controversial. In the eyes of many individuals campaigning on its behalf, marijuana right-fully belongs with other pain remedies. In fact, for many years, it was sold under highly controlled conditions in cigarette form by the Federal government for just that purpose.

In 1997, the National Institutes of Health held a workshop to discuss research on the possible therapeutic uses for smoked marijuana. Panel members from a number of fields re- viewed published research and heard presentations from pain experts. The panel members concluded that, because there are too few scientific studies to prove marijuana’s therapeutic utility for certain conditions, additional research is needed. There is evidence, however, that receptors to which marijuana binds are found in many brain regions that process information that can produce pain.

Nerve blocks may involve local anesthesia, regional anesthesia or analgesia, or surgery; dentists routinely use them for traditional dental procedures. Nerve blocks can also be used to prevent or even diagnose pain.

In the case of a local nerve block, any one of a number of local anesthetics may be used; the names of these compounds, such as lidocaine or novocaine, usually have an aine ending. Regional blocks affect a larger area of the body. Nerve blocks may also take the form of what is commonly called an epidural, in which a drug is administered into the space between the spine’s protective covering (the dura) and the spinal column. This procedure is most well known for its use during childbirth. Morphine and methadone are opioid nar- cotics (such drugs end in ine or one) that are sometimes used for regional analgesia and are administered as an injection.

Neurolytic blocks employ injection of chemical agents such as alcohol, phenol, or glycerol to block pain messages and are most often used to treat cancer pain or to block pain in the cranial nerves. In some cases, a drug called guanethidine is administered intravenously in order to accomplish the block.

Surgical blocks are performed on cranial, peripheral, or sympathetic nerves. They are most often done to relieve the pain of cancer and extreme facial pain, such as that experi- enced with trigeminal neuralgia. There are several different types of surgical nerve blocks and they are not without problems and complications. Nerve blocks can cause muscle paralysis and, in many cases, result in at least partial numbness. For that reason, the procedure should be reserved for a select group of patients and should only be performed by skilled surgeons.

Types of surgical nerve blocks include:

Source: “Pain: Hope Through Research,” NINDS. Publication date December 2001.

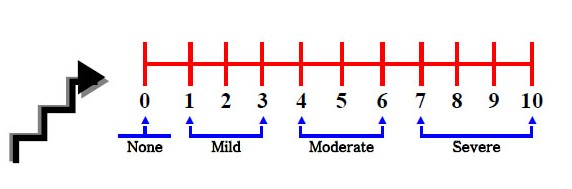

The following pain intensity scales are used by researchers at the NIH Clinical Center to measure how intensely individuals are feeling pain and to monitor the effectiveness of treat- ments. Some of the scales are appropriate for children and adults; others are used for infants.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

0 – 10 Numeric Rating Scale (page 1 of 1)

|

|

Indications: Adults and children (> 9 years old) in all patient care settings who are able to use numbers to rate the intensity of their pain.

Instructions:

Reference

McCaffery, M., & Beebe, A. (1993). Pain: Clinical Manual for Nursing Practice. Baltimore: V.V. Mosby Company.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

Wong–Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale (page 1 of 1)

|

|

|

|

Indications: Adults and children (> 3 years old) in all patient care settings.

Instructions:

Reference

Wong, D. and Whaley, L. (1986). Clinical handbook of pediatric nursing, ed., 2, p. 373. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Company.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

COMFORT Scale (page 2 of 2)

Reference

Ambuel, ., Hamlett, KW, Marx, CM, & Blumer, JL (1992). Assessing distress in pediatric intensive care environments: the COMFORT Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 17(1): 95-109.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

CRIES Pain Scale (page 1 of 1)

|

DATE/TIME |

||||||

| Crying - Characteristic cry of pain is high pitched. 0 – No cry or cry that is not high-pitched 1 - Cry high pitched but baby is easily consolable 2 - Cry high pitched but baby is inconsolable |

||||||

| Requires O2 for SaO2 < 95% - Babies experiencing pain manifest decreased oxygenation. Consider other causes of hypoxemia, e.g., oversedation, atelectasis, pneumothorax) 0 – No oxygen required 1 – < 30% oxygen required 2 – > 30% oxygen required |

||||||

| Increased vital signs (BP* and HR*) - Take BP last as this may awaken child making other assessments difficult 0 – Both HR and BP unchanged or less than baseline 1 – HR or BP increased but increase in < 20% of baseline 2 – HR or BP is increased > 20% over baseline. |

||||||

| Expression - The facial expression most often associated with pain is a grimace. A grimace may be characterized by brow lowering, eyes squeezed shut, deepening naso-labial furrow, or open lips and mouth. 0 – No grimace present 1 – Grimace alone is present 2 – Grimace and non-cry vocalization grunt is present |

||||||

| Sleepless - Scored based upon the infant’s state during the hour preceding this recorded score. 0 – Child has been continuously asleep 1 – Child has awakened at frequent intervals 2 – Child has been awake constantly |

||||||

|

TOTAL SCORE |

* Use baseline preoperative parameters from a non-stressed period. Multiply baseline HR by 0.2 then add to baseline HR to determine the HR that is 20% over baseline. Do the same for BP and use the mean BP.

Indications: For neonates (0 – 6 months)

Instructions:

Each of the five (5) categories is scored from 0-2, which results in a total score between 0 and 10. The interdisciplinary team in collaboration with the patient/family (if appropriate), can determine appropriate interventions in response to CRIES Scale scores.

Reference

Krechel, SW & Bildner, J. (1995). CRIES: a new neonatal postoperative pain measurement score – initial testing of validity and reliability. Paediatric Anaesthesia, 5: 53-61.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

FLACC Scale (page 1 of 1)

|

DATE/TIME |

||||||

| Face 0 - No particular expression or smile 1 - Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested 2 - Frequent to constant quivering chin, clenched jaw |

||||||

| Legs 0 – Normal position or relaxed 1 – Uneasy, restless, tense 2 – Kicking, or legs drawn up |

||||||

| Activity 0 – Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily 1 – Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense 2 – Arched, rigid or jerking |

||||||

| Cry 0 – No cry (awake or asleep) 1 – Moans or whimpers; occasional complaint 2 - Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints |

||||||

| Consolability 0 – Content, relaxed 1 – Reassured by occasional touching, hugging or being talked to, distractible 2 – Difficult to console or comfort |

||||||

|

TOTAL SCORE |

Indications: Infants and children (2 months – 7 years) unable to validate the presence of or quantify the severity of pain.

Instructions:

Reference

Merkel, SI, Voepel-Lewis, T., Shayevitz, JR, & Malviya, S. (1997). The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatric Nursing, 23(3): 293-297.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

WARREN GRANT MAGNUSON CLINICAL CENTER

PAIN INTENSITY INSTRUMENTS

JULY 2003

Checklist of Non-Verbal Indicators (CNVI) (page 1 of 1)

|

With Movement |

At Rest |

|

| Vocal Complaints – nonverbal expression of pain demonstrated by moans, groans, grunts, cries, gasps, sighs) | ||

| Facial Grimaces and Winces – furrowed brow, narrowed eyes, tightened lips, dropped jaw, clenched teeth, distorted expression | ||

| Bracing – clutching or holding onto siderails, bed, tray table, or affected area during movement | ||

| Restlessness – constant or intermittent shifting of position, rocking, intermittent or constant hand motions, inability to keep still | ||

| Vocal complaints – verbal expression of pain using words, e.g., “ouch” or “that hurts; ” cursing during movement, or exclamations of protest, e.g., “stop” or “that’s enough.” | ||

|

TOTAL SCORE |

Indications: Behavioral Health adults who are unable to validate the presence of or quantify the severity of pain using either the Numerical Rating Scale or the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale.

Instructions:

Reference

Feldt, KS. (2000). The checklist of nonverbal pain indicators (CNPI). Pain Management Nursing, 1(1): 13-21.