| Contents | Previous | Next |

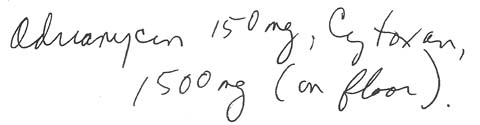

A nurse working the day shift prepared to administer medication to the 50 patients on her medical unit. A medication administration record (MAR) written the evening before for an 80-pound (36-kg) woman with breast cancer had this order:

|

|

Because the nurse didn't know what "on floor" meant, she asked her head nurse. The head nurse explained it meant to have the drugs available so the intern could give them ... and she reminded the medication nurse that only doctors could give I.V. chemotherapeutic drugs.

Because the doses of Adriamycin (doxorubicin HCI) and Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide) seemed high for this small patient, the nurse checked the MAR against the doctor's original order. The transcription was correct, so she got the drugs from the pharmacy.

When she returned, she found the intern and said, "Here are the drugs for you to give Mrs. Smith. Nurses don't give I.V. chemotherapy." She then watched the intern prepare the medication and administer it--all of it-to the patient.

That evening, the patient's doctor came to the unit and asked for the medication he had ordered the evening before. The intern told him he had administered the entire dose of both drugs to the patient.

The astonished doctor quickly checked his patient. Because of his concern that her blood cell count would drop drastically, he placed her in reverse isolation for the next 2 weeks. She had a fever, suffered severe nausea and vomiting, and eventually needed numerous blood transfusions. Fortunately, she didn't develop cardiotoxicity, which can result from an overdose of Adriamycin.

The patient was lucky to bear this high dose of highly toxic drugs. Nevertheless, all involved in the error were horrified by it--especially the nurse, who was blamed for the error.

Actually, several errors were made. First, the patient's doctor wrote an incomplete order. He didn't specify that he wanted the drugs on the floor so he could give them in divided doses over several days. He also neglected to specify time and route of administration.

The nurse, though she thought the doses seemed high, assumed that because the doctor was an expert in oncology, the order was correct. She also assumed the intern was familiar with the protocol for administering the drugs. The head nurse added to the confusion by not questioning the order herself.

The pharmacist compounded the error by dispensing an incomplete order. Finally, the intern administered the drugs in one dose without checking the protocol and because he thought the medication nurse had told him to do it.

All these people contributed to the error by not checking with the prescribing doctor to confirm that the order was correct. Each assumed the other knew what he was doing.

Obviously, you should never assume anything when you're responsible for medication administration. But for highly toxic cancer drugs, still more safeguards are needed in hospital policies and procedures.

For example, the hospital could require that all chemotherapy orders be written during the day, when a full staff of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists are available to double-check them. The hospital could post its chemotherapy protocols on each nursing unit. Or it could establish a cancer chemotherapy unit and require that everyone on this unit be familiar with the drugs' protocols.

Whatever the policy in the hospital where you work, remember: When you're working with cancer drugs, you're responsible for their safe administration. If the drug order seems unclear, don't assume it's correct-confirm it with the prescribing doctor.