| Contents | Previous | Next |

Narcolepsy is a disabling neurological disorder of sleep regulation that affects the control of sleep and wakefulness. It may be described as an intrusion of the dreaming state of sleep (called REM or rapid eye movement sleep) into the waking state. Symptoms generally begin between the ages of 15 and 30. The four classic symptoms of the disorder are excessive daytime sleepiness; cataplexy (sudden, brief episodes of muscle weakness or paralysis (such as limpness at the neck or knees, sagging facial muscles, or inability to speak clearly) brought on by strong emotions such as laughter, anger, surprise or anticipation); sleep paralysis (paralysis upon falling asleep or waking up); and hypnagogic hallucinations (vivid dream-like images that occur at sleep onset). Disturbed nighttime sleep, including tossing and turning in bed, leg jerks, nightmares, and frequent awakenings, may also occur.

The development, number and severity of symptoms vary widely among individuals with the disorder. It is probable that there is an important genetic component to the disorder as well. Unrelenting excessive sleepiness is usually the first and most prominent symptom of narcolepsy. Patients with the disorder experience irresistible sleep attacks, throughout the day, which can last for 30 seconds to more than 30 minutes, regardless of the amount or quality of prior nighttime sleep. These attacks result in episodes of sleep at work and social events, while eating, talking and driving, and in other similarly inappropriate occasions. Although narcolepsy is not a rare disorder, it is often misdiagnosed or diagnosed only years after symptoms first appear. Early diagnosis and treatment, however, are important to the physical and mental well-being of the affected individual.

Daytime sleepiness, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations can also occur in people who do not have narcolepsy.

Only about 20 to 25 percent of people with narcolepsy experience all four symptoms. The excessive daytime sleepiness generally persists throughout life, but sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations may not. The symptoms of narcolepsy, especially the excessive daytime sleepiness and cataplexy, often become severe enough to cause serious disruptions in a person’s social, personal, and professional lives and severely limit activities.

You should be checked for narcolepsy if:

Although it is estimated that narcolepsy afflicts as many as 200,000 Americans, fewer than 50,000 are diagnosed. It is as widespread as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis and more prevalent than cystic fibrosis, but it is less well known. Narcolepsy is often mistaken for depression, epilepsy, or the side effects of medications.

Narcolepsy can occur in both men and women at any age, although its symptoms are usually first noticed in teenagers or young adults. There is strong evidence that narcolepsy may run in families; 8 to 12 percent of people with narcolepsy have a close relative with the disease.

Normally, when an individual is awake, brain waves show a regular rhythm. When a person first falls asleep, the brain waves become slower and less regular. This sleep state is called non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. After about an hour and a half of NREM sleep, the brain waves begin to show a more active pattern again, even though the person is in deep sleep. This sleep state, called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, is when dreaming occurs.

In narcolepsy, the order and length of NREM and REM sleep periods are disturbed, with REM sleep occurring at sleep onset instead of after a period of NREM sleep. Thus, narcolepsy is a disorder in which REM sleep appears at an abnormal time. Also, some of the aspects of REM sleep that normally occur only during sleep—lack of muscle tone, sleep paralysis, and vivid dreams—occur at other times in people with narcolepsy. For example, the lack of muscle tone can occur during wakefulness in a cataplexy episode. Sleep paralysis and vivid dreams can occur while falling asleep or waking up.

Diagnosis is relatively easy when all the symptoms of narcolepsy are present. But if the sleep attacks are isolated and cataplexy is mild or absent, diagnosis is more difficult. Two tests that are commonly used in diagnosing narcolepsy are the polysomnogram and the multiple sleep latency test. These tests are usually performed by a sleep specialist. The polysomnogram involves continuous recording of sleep brain waves and a number of nerve and muscle functions during nighttime sleep. When tested, people with narcolepsy fall asleep rapidly, enter REM sleep early, and may awaken often during the night. The polysomnogram also helps to detect other possible sleep disorders that could cause daytime sleepiness.

For the multiple sleep latency test, a person is given a chance to sleep every 2 hours during normal wake times. Observations are made of the time taken to reach various stages of sleep. This test measures the degree of daytime sleepiness and also detects how soon REM sleep begins. Again, people with narcolepsy fall asleep rapidly and enter REM sleep early.

Although there is no cure for narcolepsy, treatment options are available to help reduce the various symptoms. Treatment is individualized depending on the severity of the symptoms, and it may take weeks or months for an optimal regimen to be worked out. Complete control of sleepiness and cataplexy is rarely possible. Treatment is primarily by medications, but lifestyle changes are also important. The main treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy is with a group of drugs called central nervous system stimulants. For cataplexy and other REM-sleep symptoms, antidepressant medications and other drugs that suppress REM sleep are prescribed. Caffeine and over-the-counter drugs have not been shown to be effective and are not recommended.

In addition to drug therapy, an important part of treatment is scheduling short naps (10 to 15 minutes) two to three times per day to help control excessive daytime sleepiness and help the person stay as alert as possible. Daytime naps are not a replacement for nighttime sleep.

Ongoing communication among the physician, the person with narcolepsy, and family members about the response to treatment is necessary to achieve and maintain the best control.

Studies supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are trying to increase understanding of what causes narcolepsy and improve physicians’ ability to detect and treat the disease. Scientists are studying narcolepsy patients and families, looking for clues to the causes, course, and effective treatment of this sleep disorder.

One of the first breakthroughs came in the 1970s, when researchers found that narcolepsy was more than a human disease. It turns out, for example, that it also strikes Doberman pinschers. The narcoleptic dogs will inexplicably conk out while playing or experience cataplexy when they sniff their favorite food. Since the finding, scientists have scrutinized these dog models of the disease as well as other animal models. Their investigations recently led to several discoveries.

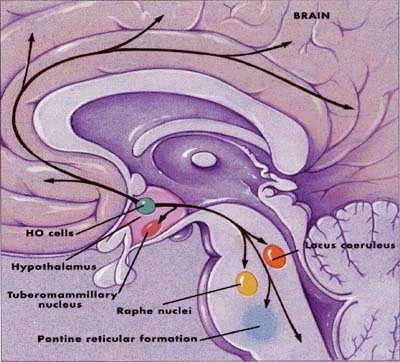

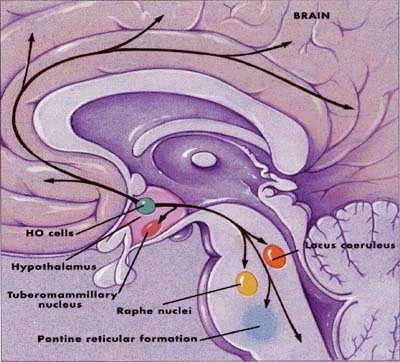

The cells that produce that small peptides, HO, reside in the hypothalamus, an area deep in the brain. Recent rodent studies indicate that these cells connect to brain regions that are involved in sleep and wakefulness, including the locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, tuberomammillary nucleus and pontine reticular formation, among others. This evidence suggest that, normally, HO helps the sleep and wakefulness areas carry out their jobs. And HO-related abnormalities may impair their function.

One group of findings indicates that malfunctions in the activity of the small brain peptides, known as either hypocretins or orexins (HO), disrupt the sleep-wake cycle and lead to narcolepsy. Scientists recently found that Dobermans and Labrador retrievers with narcolepsy have a defect in a gene that appears to impair their HO activity. Normally, this gene leads to the development of a protein that recognizes the HO brain messages.

Researchers also are investigating the relationship of HO to human narcolepsy. So far, HO genes in narcoleptic humans appear mostly normal, so some scientists think that a defective gene is not the root of the human problem. Possibly some other force, such as a disease, assaults the human HO system and triggers narcolepsy. Scientists recently found that seven out of nine people with narcolepsy had undetectable levels of HO. They currently are examining the brains of dead narcoleptic humans to see if their HO-producing cells were damaged or destroyed.

Some of the specific questions being addressed in NIH-supported studies are the nature of genetic and environmental factors that might combine to cause narcolepsy and the immunological, biochemical, physiological, and neuromuscular disturbances associated with narcolepsy. Scientists are also working to better understand sleep mechanisms and the physical and psychological effects of sleep deprivation and to develop better ways of measuring sleepiness and cataplexy.

Learning as much about narcolepsy as possible and finding a support system can help patients and families deal with the practical and emotional effects of the disease, possible occupational limitations, and situations that might cause injury. A variety of educational and other materials are available from sleep medicine or narcolepsy organizations. Support groups exist to help persons with narcolepsy and their families.

Individuals with narcolepsy, their families, friends, and potential employers should know that:

Source: National Center on Sleep Disorders Research and Office Prevention,

Education, and Control

National Institutes of Health

August 1997

Lydia Kibiuk, Society for Neuroscience

For additional information on sleep and sleep disorders, contact the following offices of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health:

Research (NCSDR) The NCSDR supports research, scientist training, dissemination of health information, and other activities on sleep and sleep disorders. The NCSDR also coordinates sleep research activities with other Federal agencies and with public and nonprofit organizations.

National Center on Sleep Disorders Research

Two Rockledge Centre Suite 7024

6701 Rockledge Drive, MSC 7920

Bethesda, MD 20892-7920

(301) 435-0199

(301) 480-3451 (fax)

The Information Center acquires, analyzes, promotes, maintains, and disseminates programmatic and educational information related to sleep and sleep disorders.Write for a list of available publications or to order additional copies of this fact sheet.

NHLBI Information Center

P.O. Box 30105

Bethesda, MD 20824-0105

(301) 251-1222

(301) 251-1223 (fax)