Research has revealed a great deal of valuable medical, scientific, and public health information about the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The ways in which HIV can be transmitted have been clearly identified. Unfortunately, false information or statements that are not supported by scientific findings continue to be shared widely through the Internet or popular press. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has prepared this fact sheet to correct a few misperceptions about HIV.

HIV is spread by sexual contact with an infected person, by sharing needles and/or syringes (primarily for drug injection) with someone who is infected, or, less commonly (and now very rarely in countries where blood is screened for HIV antibodies), through transfusions of infected blood or blood clotting factors. Babies born to HIV-infected women may become infected before or during birth or through breast-feeding after birth.

In the healthcare setting, workers have been infected with HIV after being stuck with needles containing HIV-infected blood or, less frequently, after infected blood gets into a worker's open cut or a mucous membrane (for example, the eyes or inside of the nose). There has been only one instance of patients being infected by a healthcare worker in the United States; this involved HIV transmission from one infected dentist to six patients. Investigations have been completed involving more than 22,000 patients of 63 HIV-infected physicians, surgeons, and dentists, and no other cases of this type of transmission have been identified in the United States. Some people fear that HIV might be transmitted in other ways; however, no scientific evidence to support any of these fears has been found. If HIV were being transmitted through other routes (such as through air, water, or insects), the pattern of reported AIDS cases would be much different from what has been observed. For example, if mosquitoes could transmit HIV infection, many more young children and preadolescents would have been diagnosed with AIDS. All reported cases suggesting new or potentially unknown routes of transmission are thoroughly investigated by state and local health departments with the assistance, guidance, and laboratory support from CDC. No additional routes of transmission have been recorded, despite a national sentinel system designed to detect just such an occurrence. The following paragraphs specifically address some of the common misperceptions about HIV transmission.Scientists and medical authorities agree that HIV does not survive well in the environment, making the possibility of environmental transmission remote. HIV is found in varying concentrations or amounts in blood, semen, vaginal fluid breast milk, saliva, and tears. To obtain data on the survival of HIV, laboratory studies have required the use of artificially high concentrations of laboratory-grown virus. Although these unnatural concentrations of HIV can be kept alive for days or even weeks under precisely controlled and limited laboratory conditions, CDC studies have shown that drying of even these high concentrations of HIV reduces the amount of infectious virus by 90 to 99 percent within several hours. Since the HIV concentrations used in laboratory studies are much higher than those actually found in blood or other specimens, drying of HIV-infected human blood or other body fluids reduces the theoretical risk of environmental transmission to that which has been observed–essentially zero. Incorrect interpretation of conclusions drawn from laboratory studies have unnecessarily alarmed some people.

Results from laboratory studies should not be used to assess specific personal risk of infection because (1) the amount of virus studied is not found in human specimens or elsewhere in nature, and (2) no one has been identified as infected with HIV due to contact with an environmental surface. Additionally, HIV is unable to reproduce outside its living host (unlike many bacteria or fungi, which may do so under suitable conditions), except under laboratory conditions, therefore, it does not spread or maintain infectiousness outside its host.Although HIV has been transmitted between family members in a household setting, this type of transmission is very rare. These transmissions are believed to have resulted from contact between skin or mucous membranes and infected blood. To prevent even such rare occurrences, precautions should be taken in all settings including the home to prevent exposures to the blood of persons who are HIV infected, at risk for HIV infection, or whose infection and risk status are unknown. For example,

| Gloves should be worn during contact with blood or other body fluids that could possibly contain visible blood such as urine, feces, or vomit. | |

| Cuts, sores, or breaks on both the care giver's and patient's exposed skin should be covered with bandages. | |

| Hands and other parts of the body should be washed immediately after contact with blood or other body fluids and surfaces soiled with blood should be disinfected appropriately. | |

| Practices that increase the likelihood of blood contact, such as sharing of razors and toothbrushes, should be avoided. | |

| Needles and other sharp instruments should be used only when medically necessary and handled according to recommendations for healthcare settings. (Do not put caps back on needles by hand or remove needles from syringes. Dispose of needles in puncture-proof containers |

There is no known risk of HIV transmission to co-workers, clients, or consumers from contact in industries such as food-service establishments (see information on survival of HIV in the environment). Food-service workers known to be infected with HIV need not be restricted from work unless they have other infections or illnesses (such as diarrhea or hepatitis A) for which any food-service worker, regardless of HIV infection status, should be restricted. CDC recommends that all food-service workers follow recommended standards and practices of good personal hygiene and food sanitation.

In 1985, CDC issued routine precautions that all personal-service workers (such as hairdressers, barbers cosmetologists, and massage therapists) should follow, even though there is no evidence of transmission from a personal-service worker to a client or vice versa. Instruments that are intended to penetrate the skin (such as tattooing and acupuncture needles, ear piercing devices) should be used once and disposed of or thoroughly cleaned and sterilized. Instruments not intended to penetrate the skin but which may become contaminated with blood (for example razors) should be used for only one client and disposed of or thoroughly cleaned and disinfected after each use. Personal-service workers can use the same cleaning procedures that are recommended for healthcare institutions. CDC knows of no instances of HIV transmission through tattooing or body piercing, although hepatitis B virus has been transmitted during some of these practices. One case of HIV transmission from acupuncture has been documented. Body piercing (other than ear piercing) is relatively new in the United States, and the medical complications for body piercing appear to be greater than for tattoos. Healing of piercings generally will take weeks, and sometimes even months, and the pierced tissue could conceivably be abraded (torn or cut) or inflamed even after healing. Therefore, a theoretical HIV transmission risk does exist if the unhealed or abraded tissues come into contact with an infected person's blood or other infectious body fluid. Additionally, HIV could be transmitted if instruments contaminated with blood are not sterilized or disinfected between clients.Casual contact through closed-mouth or social kissing is not a risk for transmission of HIV. Because of the potential for contact with blood during French or open-mouth kissing, CDC recommends against engaging in this activity with a person known to be infected. However, the risk of acquiring HIV during open-mouth kissing is believed to be very low. CDC has investigated only one case of HIV infection that may be attributed to contact with blood during open-mouth kissing.

In 1997, CDC published findings from a state health department investigation of an incident that suggested blood-to-blood transmission of HIV by a human bite. There have been other reports in the medical literature in which HIV appeared to have been transmitted by a bite. Severe trauma with extensive tissue tearing and damage and presence of blood were reported in each of these instances. Biting is not a common way of transmitting HIV. In fact, there are numerous reports of bites that did not result in HIV infection.

HIV has been found in saliva and tears in very low quantities from some AIDS patients. It is important to understand that finding a small amount of HIV in a body fluid does not necessarily mean that HIV can be transmitted by that body fluid. HIV has not been recovered from the sweat of HIV-infected persons. Contact with saliva, tears, or sweat has never been shown to result in transmission of HIV.

From the onset of the HIV epidemic, there has been concern about transmission of the virus by biting and bloodsucking insects. However, studies conducted by researchers at CDC and elsewhere have shown no evidence of HIV transmission through insects—even in areas where there are many cases of AIDS and large populations of insects such as mosquitoes. Lack of such outbreaks, despite intense efforts to detect them, supports the conclusion that HIV is not transmitted by insects.

The results of experiments and observations of insect biting behavior indicate that when an insect bites a person, it does not inject its own or a previously bitten person's or animal's blood into the next person bitten. Rather, it injects saliva, which acts as a lubricant or anticoagulant so the insect can feed efficiently. Such diseases as yellow fever and malaria are transmitted through the saliva of specific species of mosquitoes. However, HIV lives for only a short time inside an insect and, unlike organisms that are transmitted via insect bites, HIV does not reproduce (and does not survive) in insects. Thus, even if the virus enters a mosquito or another sucking or biting insect, the insect does not become infected and cannot transmit HIV to the next human it feeds on or bites. HIV is not found in insect feces. There is also no reason to fear that a biting or bloodsucking insect, such as a mosquito, could transmit HIV from one person to another through HIV-infected blood left on its mouth parts. Two factors serve to explain why this is so–first infected people do not have constant, high levels of HIV in their bloodstreams and, second, insect mouth parts do not retain large amounts of blood on their surfaces. Further, scientists who study insects have determined that biting insects normally do not travel from one person to the next immediately after ingesting blood. Rather, they fly to a resting place to digest this blood meal.Condoms are classified as medical devices and are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Condom manufacturers in the United States test each latex condom for defects, including holes, before it is packaged. The proper and consistent use of latex or polyurethane (a type of plastic) condoms when engaging in sexual intercourse–vaginal, anal, or oral–can greatly reduce a person's risk of acquiring or transmitting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV infection.

There are many different types and brands of condoms available–however, only latex or polyurethane condoms provide a highly effective mechanical barrier to HIV. In laboratories, viruses occasionally have been shown to pass through natural membrane (skin or lambskin) condoms, which may contain natural pores and are therefore not recommended for disease prevention (they are documented to be effective for contraception). Women may wish to consider using the female condom when a male condom cannot be used. For condoms to provide maximum protection, they must be used consistently (every time) and correctly. Several studies of correct and consistent condom use clearly show that latex condom breakage rates in this country are less than 2 percent. Even when condoms do break, one study showed that more than half of such breaks occurred prior to ejaculation. When condoms are used reliably, they have been shown to prevent pregnancy up to 98 percent of the time among couples using them as their only method of contraception. Similarly, numerous studies among sexually active people have demonstrated that a properly used latex condom provides a high degree of protection against a variety of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV infection.In 1984, 3 years after the first reports of a disease that was to become known as AIDS, researchers discovered the primary causative viral agent, the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). In 1986, a second type of HIV, called HIV-2, was isolated from AIDS patients in West Africa, where it may have been present decades earlier. Studies of the natural history of HIV-2 are limited, but to date comparisons with HIV-1 show some similarities while suggesting differences. Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 have the same modes of transmission and are associated with similar opportunistic infections and AIDS. In persons infected with HIV-2, immunodeficiency seems to develop more slowly and to be milder. Compared with persons infected with HIV-1, those with HIV-2 are less infectious early in the course of infection. As the disease advances, HIV-2 infectiousness seems to increase; however, compared with HIV-1, the duration of this increased infectiousness is shorter. HIV-1 and HIV-2 also differ in geographic patterns of infection; the United States has few reported cases.

HIV-2 infections are predominantly found in Africa. West African nations with a prevalence of HIV-2 of more than 1% in the general population are Cape Verde, Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mauritania Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. Other West African countries reporting HIV-2 are Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia Niger, São Tomé, Senegal, and Togo. Angola and Mozambique are other African nations where the prevalence of HIV-2 is more than 1%.

*Prevalence is the proportion of cases present in a population at a given point in time.The first case of HIV-2 infection in the United States was diagnosed in 1987. Since then, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has worked with state and local health departments to collect demographic, clinical, and laboratory data on persons with HIV-2 infection.

Of the 79 infected persons, 66 are black and 51 are male. Fifty-two were born in West Africa, 1 in Kenya, 7 in the United States, 2 in India, and 2 in Europe. The region of origin was not known for 15 of the persons, although 4 of them had a malaria-antibody profile consistent with residence in West Africa. AIDS-defining conditions have developed in 17 and 8 have died. These case counts represent minimal estimates because completeness of reporting has not been assessed. Although AIDS is reported uniformly nationwide, the reporting of HIV infection, including HIV-2 infection, differs from state to state according to state policy.Because epidemiologic data indicate that the prevalence of HIV-2 in the United States is very low, CDC does not recommend routine HIV-2 testing at U.S. HIV counseling and test sites or in settings other than blood centers. However when HIV testing is to be performed, tests for antibodies to both HIV-1 and HIV-2 should be obtained if demographic or behavioral information suggests that HIV-2 infection might be present.

| Sex partners of a person from a country where HIV-2 is endemic (refer to countries listed earlier) | |

| Sex partners of a person known to be infected with HIV-2 | |

| People who received a blood transfusion or a nonsterile injection in a country where HIV-2 is endemic | |

| People who shared needles with a person from a country where HIV-2 is endemic or with a person known to be infected with HIV-2 | |

| Children of women who have risk factors for HIV-2 infection or are known to be infected with HIV-2 | |

| HIV-2 testing also is indicated for People with an illness that suggests HIV infection (such as an HIV-associated opportunistic infection) but whose HIV-1 test result is not positive | |

| People for whom HIV-1 Western blot exhibits the unusual indeterminate test band pattern of gag (p55, p24, or p17) plus pol (p66, p51, or p32) in the absence of env (gp160, gp120, or gp41) |

Since 1992, all U.S. blood donations have been tested with a combination HIV-1/HIV-2 enzyme immunoassay test kit that is sensitive to antibodies to both viruses. This testing has demonstrated that HIV-2 infection in blood donors is extremely rare. All donations detected with either HIV-1 or HIV-2 are excluded from any clinical use, and donors are deferred from further donations.

Little is known about the best approach to the clinical treatment and care of patients infected with HIV-2. Given the slower development of immunodeficiency and the limited clinical experience with HIV-2, it is unclear whether antiretroviral therapy significantly slows progression. Not all of the drugs used to treat HIV-1 infection are as effective against HIV-2. In vitro (laboratory) studies suggest that nucleoside analogs are active against HIV-2, though not as active as against HIV-1. Protease inhibitors should be active against HIV-2. However, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) are not active against HIV-2. Whether any potential benefits would outweigh the possible adverse effects of treatment is unknown.

Monitoring the treatment response of patients infected with HIV-2 is more difficult than monitoring people infected with HIV-1. No FDA-licensed HIV-2 viral load assay is available yet. Viral load assays used for HIV-1 are not reliable for monitoring HIV-2. Response to treatment for HIV-2 infection may be monitored by following CD4+ T-cell counts and other indicators of immune system deterioration, such as weight loss, oral candidiasis, unexplained fever, and the appearance of a new AIDS-defining illness. More research and clinical experience is needed to determine the most effective treatment for HIV-2. The optimal timing for antiretroviral therapy (i.e., soon after infection, when symptoms appear, or when CD4+ T cell counts fall below a certain level) remains under review by clinical experts. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents, by the Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection, may be helpful to the clinician who is caring for a patient infected with HIV-2; however, the recommendations on viral load monitoring and the use of NNRTIs would not apply to patients with HIV-2 infection.HIV-2 infection in children is rare. Compared with HIV-1, HIV-2 seems to be less transmissible from an infected mother to her child. However, cases of transmission from an infected woman to her fetus or newborn have been reported among women who had primary HIV-2 infection during their pregnancy.

Zidovudine therapy has been demonstrated to reduce the risk for perinatal HIV-1 transmission and also might prove effective for reducing perinatal HIV-2 transmission. Zidovudine therapy should be considered for HIV-2-infected expectant mothers and their newborns, especially for women who become infected during pregnancy.Physicians caring for patients with HIV-2 infection should decide whether to initiate antiretroviral therapy after discussing with their patients what is known, what is not known, and the possible adverse effects of treatment.

Continued surveillance is needed to monitor HIV-2 in the U.S. population because the possibility for further spread of HIV-2 exists, especially among injecting drug users and people with multiple sex partners. Programs aimed at preventing the transmission of HIV-1 also can help to prevent and control the spread of HIV-2.

The successful introduction and spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) into the global human population has occurred for many reasons. The discovery and wide spread use of penicillin and other antibiotics meant that there was treatment and cure for most sexually transmitted diseases. The existence of these new drugs changed how people perceived risks associated with sexual activity. Soldiers in World War II increasingly used prophylactics and the subsequent development of hormonal contraceptives hastened the pace of change in sexual practices, as prevention of pregnancy became a real possibility. Lifestyles also were changing: people were moving into regions that were previously uninhabited by man and long distance travel became easier and was much more common, allowing for more social migration and sexual mixing. Although the virus may have first been introduced to humans earlier in the 20th century (most likely contracted from infected animals), it was in the 1970s that wider dissemination occurred.

For industrialized countries, the first evidence of the AIDS epidemic was among groups of individuals who shared a common exposure risk. In the United States, sexually active homosexual men were among the first to present with manifestations of HIV disease, followed by recipients of blood or blood products, then injection drug users, and ultimately children of mothers at risk.

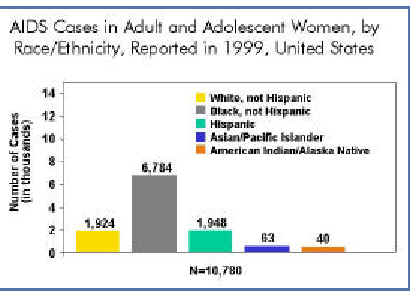

Women have represented an increasing proportion of reported AIDS cases in the United States, accounting for 23% of adult cases from July 1998-June 1999. (CDC, 1999) Eighty percent of AIDS cases in women are in African Americans and Hispanics, as compared to 61% of cases in men.

In developing countries, the AIDS epidemic manifested itself quite differently, both because the signs and symptoms were harder to identify due to other competing causes of morbidity and mortality and because the epidemic did not seem to be limited to high-risk groups and, instead, was more generalized. Worldwide, women now represent 43% of all adults living with HIV and AIDS (Table 1-1, next page) and this proportion had been steadily increasing over time. (UNAIDS, 1998) This chapter reviews the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS: beginning with how HIV is transmitted and the variables involved; the natural history of HIV infection in women, both without treatment and in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART); and concludes with future issues regarding the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: UNAIDS and WHO (2001), AIDS Epidemic Update: December 2001 (Geneva, 2001), p. 3.

Notes: * The proportion of adults (15 to 49 years of age) living with HIV/AIDS in 2000, using 2001 population number. ** Hetero (heterosexual transmission), IDU (transmission through infecting drug use), MSM (sexual transmission among men who have sex with men).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that HIV is transmitted by three primary routes: sexual, parenteral (blood-born), and perinatal. Virtually all cases of HIV transmission can be attributed to these exposure categories.

Transmission rates from the infected host to the uninfected recipient vary by both mode of transmission and the specific circumstances. Since HIV is a relatively large virus, has a short half-life in vitro, and can only live in primates, HIV cannot be transmitted from causal (i.e. hugging or shaking hands) or surface (i.e. toilet seats) contact or from insect bites.

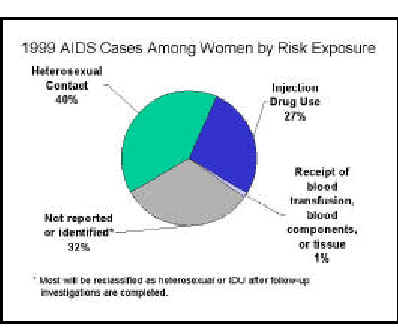

Sexual transmission of HIV from an infected partner to an uninfected partner can occur through male-to-female, female-to-male, male-to-male, and female-to-female sexual contact. Worldwide, sexual transmission of HIV is the predominant mode of transmission. (Quinn, 1996) Among U.S. women with AIDS, sexual transmission constitutes 40% of reported cases as of June 1999. (CDC, 1999) This 40% is probably an underestimate when you take into consideration that a large proportion of the women with AIDS who report no identifiable risk (an additional 15% of AIDS cases in women) are actually also infected via sexual transmission. While receptive rectal and vaginal intercourse appear to present the greatest risk of infection (approximately 0.13% and 0.10.2%, respectively, per episode), insertive intercourse (both rectal and vaginal) have also been associated with HIV infection (approximately 0.06% and 0.1%, respectively, per episode). (Vittinghoff, 1999; Mastro, 1996) In addition, there have been a few case reports of male-to-male transmission from receptive oral intercourse with an HIV-infected male partner (approximately 0.04% per contact) and female-to-female transmission from oral-vaginal, oral-anal, and digital intercourse. (Marmor, 1986; Monini, 1996; Monzon, 1987; Perry, 1989; Rich, 1993; Sabatini, 1983). Parenteral transmission of HIV has occurred in recipients of blood and blood products, either through transfusion (estimated 95% risk of infection from transfusion of a single unit of HIV-infected whole blood (CDC, 1998)) or clotting factors, in intravenous or injection drug users through the sharing of needles (approximately 0.67% risk per exposure (Kaplan, 1992)), and in healthcare workers through needle sticks (approximately 0.4% risk per exposure, depending on the size and location of the inoculum (Tokar, 1993)) and less commonly mucous membrane exposure. (Hessol, 1989) Among cumulatively reported AIDS cases in U.S. women through June 1999, 42% had injection drug use as their exposure risk and 3% receipt of blood, blood products, or tissue. (CDC, 1999) Parenteral transmission patterns vary by geographic region due to social and economic factors. For instance, in regions where the prevalence of HIV infection is higher, the risk of occupational or nosocomial transmission of HIV is increased over regions where there is lower prevalence. (Consten, 1995) The transmission risk is therefore related to the prevalence of HIV in the population as well as the frequency of exposure to infected body fluids and organs and the method of exposure. (Fraser, 1995) In addition, many developing countries that have a high prevalence of HIV infection also lack the resources to implement universal precautions adequately (Gilks, 1998) and may experience a greater amount of transfusion-associated HIV transmission due to a lack of HIV antibody screening in some areas, a higher residual risk of contamination in blood supplies despite antibody screening (McFarland, 1997), and high rates of transfusion in some groups of patients.

Perinatal transmission can occur in utero, during labor and delivery, or post-partum through breast-feeding. (Gwinn, 1996) Perinatal transmission rates average 2530% (Blanche, 1989), but vary by maternal stage of disease, use of antiviral therapy, duration of ruptured membranes, practice of breast-feeding, as well as other factors. In the U.S. as of June 1999, 91% of cumulative pediatric AIDS cases were attributed to perinatal transmission.Transmission of HIV infection can be influenced by several factors, including characteristics of the HIV-infected host, the recipient, and the quantity and infectivity of the virus. A summary of factors affecting sexual transmission of HIV is presented in Table 1-2.

There is an association between the quantity of virus transmitted and the risk of HIV infection. (Roques, 1993) Several studies have found that HIV-infected persons may be more likely to transmit the infection when viral replication is high, both during the initial stage of infection (Palasanthiran, 1993) and at more advanced stages of HIV disease. (Laga 1989) People with high blood viral load are more likely to transmit HIV to recipients of blood, their sexual partners, and their offspring. (Vernazza, 1999; Quinn, 2000) HIV has been quantified in semen (Coombs, 1998; Speck, 1999; Vernazza, 1997) and detected in female genital secretions (Ghys, 1997; Mostad, 1998), and virus in these locations may facilitate transmission. However, the association between infectivity and disease stage is not absolute; HIV-infected women may transmit virus to a first-born child while not to a second-born child (deNartubim 1991), and temporal studies of semen from HIV-infected men demonstrate waxing and waning viral titers over time. (Krieger, 1991; Tindall, 1992) Factors that decrease viral titers, including anti-retroviral therapy, may decrease but not eliminate the risk of HIV transmission. (Hamed, 1993) Zidovudine has been shown to reduce vertical transmission from mothers to their fetus even when administered late in pregnancy or during labor. (CDC, 1998) (See Chapter VII on HIV and Reproduction) Individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy have also shown reduced transmission rates of HIV to their sex partners. (Musicco, 1994) Several studies have suggested that anti-retroviral treatment reduces detection of HIV in female genital secretions (Cu Uvin,1998) and the concentration of HIV in semen. (Gilliam, 1997; Gupta, 1997) Providers counseling patients on treatment should be clear that precautions to prevent transmission of the virus should be maintained since not all treatment reduce infectiousness and transmissions have been reported among individuals with undetectable HIV RNA levels. (The European Collaborative Study Group, 1999) Factors which increase the risk of exposure to blood, such as genital ulcer disease (Cameron, 1989; Plummer, 1991), trauma during sexual contact (Marmor, 1986), and menstruation of an HIV-infected woman during sexual contact (The European Collaborative Study Group, 1992; Nair, 1993; St. Louis, 1993) may all increase the risk of transmission.

Method of contraception also affects the likelihood of HIV transmission. (Daly, 1994) There is overwhelming evidence that the correct and consistent use of latex condoms protect both men and women against HIV. However, because of methodologic difficulties in studies of contraceptive use and HIV transmission, it remains unclear whether the use of hormonal contraceptives, IUDs and spermicides alter the risk of HIV transmission.

| Biologic Factor | Host-Related Infectivity Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Concentration in Genital Secretions | Infectiousness (Transmission) | Susceptibility (Acquisition) | ||

| Mutation of chemokine-receptor gene | ? | ? | ||

| Late stage of HIV infection | Not applicable | |||

| Primary HIV infection | Not applicable | |||

| Antiretroviral therapy | ||||

| Local infection (inflammation or ulcer of reproductive tract or rectal or oral mucosa) | ||||

| Presence of cervical ectopy | ||||

| Presence of foreskin | ? | |||

| Method of contraception |

|

|

|

|

| Barrier | Not applicable |

|

|

|

|

|

Hormonal contraceptives |

|

|

|

|

|

Spermicidal agents | ? |

|

|

| Intrauterine devices | ? | ? |

|

|

| Menstruation | ? | |||

| Factors that lower cervicovaginal pH | ||||

| Immune activation | ||||

| Genital tract trauma | ||||

| Pregnancy | ||||

*The associations represented were

statistically significant in at least one study. The degrees of positivity (![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]() )

and negativity (

)

and negativity (![]() to

to

![]()

![]()

![]() )

of the associations are indicated with arrows, with three arrows indicating a

very strong association. The symbol

)

of the associations are indicated with arrows, with three arrows indicating a

very strong association. The symbol ![]() denotes that there is evidence in support of both a positive and a negative

association. A question mark indicates an unknown or hypothesized association

that is not currently supported by data.

denotes that there is evidence in support of both a positive and a negative

association. A question mark indicates an unknown or hypothesized association

that is not currently supported by data.

Royce RA, Sena A, Cates W Jr, Cohen MS. Current concepts: sexual transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1072-1078. Copyright 1997. Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Similarly, characteristics of the uninfected individual may increase the likelihood of infection for a given exposure to HIV. Specifically, inflammation or disruption of the genital or rectal mucosa (which can occur with sexually transmitted diseases and trauma), and lack of circumcision in heterosexual men may increase the risk of infection. (Cameron, 1989; Moses, 1994; Quinn, 2000) Sex during menstruation may increase womens risk of acquiring HIV infection (Lazzarin, 1991) as may bleeding during sexual intercourse. (Seidlin, 1993) In women, both uclerative and non-uclerative sexually transmitted diseases have been shown to be risk factors for getting infected with HIV. (Laga, 1993; Plummer, 1991) Cervical ectopy has been identified as a risk factor for acquisition of HIV infection in some (Nicolosi, 1994; Plourde, 1994) but not all (Mati, 1994) studies that have evaluated this condition. There is also some evidence that changes in the vaginal flora, as characterized by bacterial vaginosis, may facilitate acquisition of HIV. (Sewankambo, 1997) Non-barrier contraceptive methods have also been investigated in association with risk of HIV transmission but the results are inconclusive. The most frequently studied methods of contraception have been oral contraceptives, injectable hormones, intrauterine devices, and nonoxynol-9. (Daly, 1994; Plummer, 1998) (See Chapter III on Prevention) Traditional vaginal agents, used in African women for sexual enhancement and self-treatment of vaginal symptoms, has also been investigated as a potential cofactor for HIV transmission. (Dallabetta, 1995) For many of these studies, limitations of the study design preclude any definitive conclusions.

There is increasing evidence that host genetic or immunologic factors may protect against HIV infection. This has been investigated in cohort studies of Nairobi sex workers (Willerford, 1993) and in United States homosexual men (Dean, 1996), both of who remained uninfected despite multiple sexual exposures to HIV. Individuals who are homozygous for a null allele of CCR5 are relatively resistant to sexually transmitted infection with HIV, indicating an important, though not absolute, role for this receptor in viral transmission. However, homozygous CCR5 mutations were not found among 14 hemophiliacs who remained uninfected with HIV after being inoculated repeatedly with HIV contaminated Factor VIII concentrate from plasma during 1980-1985. (Zagury, 1998) In this study, investigators found an over production of betachemokines in most of the uninfected individuals.Several viral factors have been proposed to play a role in the transmissibility of HIV. These include phenotypic characteristics (e.g., envelope proteins required for transmission), genetic factors that control the replicative capacity and fitness of the virus, and resistance to antiviral drugs. (Vernazza, 1999) Envelope sequences can define viral quasispecies that have been phenotypically arranged according to their ability to induce syncytia formation in infected T-cells. (Paxton, 1998) It appears that the most commonly transmitted phenotype is the non-syncytia-inducing (NSI), M-tropic viral strain, which is frequently found in those who have been recently infected. During the course of HIV infection the development of a more cytopathic, syncytia-inducing (SI), T-tropic viral phenotype can be found and this is often a precursor to the development of AIDS. While some researchers have suggested that NSI isolates of HIV are preferentially transmitted (Roos, 1992), others have not been able to show preferential transmission of this isolate. (Albert, 1995) Envelope sequences can also be used to define viral subtypes, or clades, and these subtypes may also influence the transmissibility of HIV. The distribution of HIV subtypes differ according to geographic region, with A, C, D, and E predominant in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and B predominant in the United States, the Caribbean, South America, and Western Europe. (Hu, 1996) In one study, subtype E is reported to have greater tropism for Langerhans cells than subtype B (Soto-Ramirez, 1996) and may have a greater per contact transmissibility.

Lastly, the transmission characteristics of a viral strain that is resistant to certain antiretro- viral agents may differ from transmission of wild type virus. More research is needed in this emerging field of therapy-resistant virus and its characteristics.The natural history of HIV infection in adults has been extensively documented in the medical literature. The impact of gender on the manifestations and progression of HIV-disease is still being investigated. Concerns about gender-based differences in the course of HIV infection were expressed early in the epidemic. In most industrialized countries, women tended to have lower income, be un- or under-insured for health care, know less about HIV, more likely to be Black or Hispanic, and to have a personal or partner history of injection drug or cocaine use. Women also appeared to have more rapid progression of illness than men and to present with a different constellation of opportunistic conditions than men. When sophisticated statistical methods were applied that controlled for the tendency of women to receive less care and to present with more advanced disease, gender-based differences in HIV disease course appeared to lessen. More recently, however, with better measures of viral activity and infirmity, the issue of gender-based differences in rate of disease course and virologic parameters has again been raised. These new observations have prompted active research into the impact of gender, hormones and demographic factors on the outcome of HIV infection.

HIV infects and induces cell death in a variety of human cell lines. T-helper lymphocytes (also known as CD4 cells) are a major target of viral infection, and circulating CD4-cells become steadily depleted from peripheral blood in most untreated infected persons. Thus quantification of CD4-cells in blood is a rather simple way of determining cumulative immunologic damage due to HIV. Profound CD4-cell depletion is unusual in persons who do not have HIV infection and are usually iatrogenic or associated with severe illnesses, such as chemotherapy-induced eukopenia. (Aldrich, 2000) Other immunological parameters become altered with HIV-disease progression, and though often used for research purposes, they tend to be more difficult to measure and less reliable or more costly. Untreated HIV infection is a chronic illness that progresses through characteristic clinical stages; AIDS is an endpoint of HIV infection, resulting from severe immunological damage, loss of an effective immune response to specific opportunistic pathogens and tumors. AIDS is diagnosed by the occurrence of these specific infections and cancers or by CD4-cell depletion to less than 200/mm3.HIV can cause a wide range of symptoms and clinical conditions that reflect varying level of immunological injury and different predisposing factors. Certain conditions tend to occur in association with each other and at specific CD4 cell counts. Staging systems for HIV-disease facilitate clinical evaluation and planning therapeutic interventions, help determine the individual level of infirmity, and give prognostic information. Untreated HIV infection is a chronic illness that progresses through characteristic clinical stages that can be used to describe infirmity.

Several groups have produced organized staging systems to facilitate clinical evaluation and planning therapeutic interventions. In industrialized countries, the most widely used system for classifying HIV infection and AIDS in adults and adolescents was published by the United States Centers for Disease Control in 1993. (CDC, 1992) The case definition (Table 2-3) begins first with confirmation of HIV infection either via serologic testing (combination of a screening method such as enzyme immunoassay and more specific confirmatory test such as Western blot), or direct detection of HIV in patient tissue by viral culture, antigen detection or other test such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The definition of each stage of illness is then based on two types of information: peripheral blood CD4 cell counts and clinical manifestations. CD4 cell counts are placed in three strata, ranging from relatively normal (gt; 500 cells/mm3) to severe CD4 depletion (lt; 200 cells/mm3).

The clinical manifestations of HIV infection are also placed in three strata, generally in accordance with the level of immunologic dysfunction associated with the various conditions. (Table 2-3) Category A includes persons who have minimal clinical findings, clinical findings that do not indicate immune injury (including absence of symptoms), generalized lymphadenopathy or resolved acute HIV infection. Category B includes conditions that indicate the presence of a defect in cell-mediated immunity or conditions that appear to be worsened by HIV infection. Category C includes conditions that are considered AIDS defining, even in the absence of a CD4 cell count less than 200 cell/mm3. (CDC, 1992) The addition of specific laboratory measures such as plasma HIV RNA level, improves prognostic value even after the occurrence of Category C conditions. (Lyles, 1999)The CDC criteria require diagnostic testing and case confirmation methods that may not be available in developing countries, so several other sets of criteria have been proposed for these regions. Since lymphocyte subset quantitation is not widely available in many countries, the Global Program on AIDS of the World Health Organization (W.H.O.) proposed a clinically based staging system that is more broadly applicable than the CDC system. (W.H.O., 1993) The system uses clinical historical data, laboratory measures (optional) and

indices of physical activity to assess level of infirmity to establish four strata that are summarized in Table 2-4. Laboratory measures include a single assessment absolute CD4 cell count, with the option of replacing this test with total lymphocyte count, each of which are placed in three strata. CD4 cell count is a better prognostic indicator than total lymphocyte count, but the two results correlate well. (Brettle, 1993)

Clinical history and functional measures are placed in four categories that range from asymptomatic to severe disease. In general, when compared with the CDC stages, the W.H.O. system requires less diagnostic test data and fewer direct observations. The definition includes broader categories for conditions that may vary by region (e.g., disseminated infections with endemic mycoses which are common in South East Asian AIDS patients but not in the United States or Europe). The inclusion of performance scale measures permits quantitative clinical assessment that is not dependent on laboratory resources.

The four clinical stages in the W.H.O. system correlated well with CD4 cell counts and HIV RNA levels in a study of 750 Ethiopians (included 336 women) by Kassa and others. (Kassa, 1999) Other studies of patient populations have also demonstrated correlation of W.H.O. clinical stage with CD4 cell count and clinical outcome. (Morgan, 1997; Morgan, 1998; Schechter, 1995) When compared with the CDC staging, the W.H.O. clinical stages demonstrated a high degree of specificity, but a lower level of sensitivity (3565%) for HIV infection. (Gallant, 1993; Gallant, 1992) In particular all of the systems for disease staging are not perfectly sensitive and specific for HIVinfection, but can be improved by the addition of HIV serologies. (Ankrah,1994; DeCock, 1991) Modifications (Table 2-4) have been proposed that improve the prognostic accuracy of the W.H.O. system. Based on observations made in a study of AIDS mortality among Rwandan women, Lifson and colleagues proposed minor modifications of clinical history definitions, replacement of body mass index (BMI) (weight(in kg) divided by height (in m2)) for weight loss and use of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) as a laboratory indicator of infirmity. (Lifson, 1995) BMI was significantly better at predicting mortality than percentage of body weight lost over two measurements taken in one year. Both ESR and hematocrit were highly predictive of mortality over a 36 month period of observation. (Lifson, 1995) Other HIV-disease classifications, such as the Caracas definition proposed by the Pan American Health Organization (Rabeneck, 1996; Weniger, 1992) have been proposed but have not been evaluated as extensively as the CDC and W.H.O. systems.

Table 2-3. 1999 Revised Classification System For HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition For AIDS Among Adults and Adolescents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cell

categories (cells/cu mm) |

Clinical categories* | ||

| CD4 Cell Category | Clinical Category A | Clinical Category b | Clinical Category A |

| 500 cells/mm3 | A1 | B1 | C1 |

| 200-499 cells/mm3 | A2 | B2 | C2 |

| < 200 cells/mm3 | A3 | B3 | C3 |

| Category A Conditions | Category C Conditions | Category C Conditions | |

|

Asymptomatic HIV infection Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy Acute (primary) HIV infection with accompanying illness or history of acute HIV infection |

Bacillary angiomatosis Candidiasis, oropharyngeal (thrush) Candidiasis, vulvovaginal; persistent, frequent, or poorly responsive to therapy Cervical dysplasia (moderate or severe)/cervical carcinoma in situ Constitutional symptoms, such as fever (38.5 degrees centigrade) or diarrhea lasting greater than 1 month Hairy leukoplakia, oral Herpes zoster (shingles), involving at least two distinct episodes or more than one dermatome Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura Listeriosis Pelvic inflammatory disease, particularly if complicated by tubo-ovarian abscess Peripheral neuropathy |

Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs Candidiasis, esophageal Cervical cancer, invasive Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal, > 1 month Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes) Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision) Encephalopathy, HIV-related Herpes simplex; chronic ulcer(s) > 1 month; or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal > 1 month Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) Lymphoma, Burkitt's (or equivalent term) Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term) Lymphoma, primary, of brain Mycobacterium avium complex or M. kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis, any site (pulmonary or extrapulmonary) Mycobacterium, other or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) Pneumonia, recurrent Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) Salmonella septicemia, recurrent Toxoplasmosis of brain Wasting due to HIV |

|

| * | Persons in categories A3, B3, C1, C2, and C3 have AIDS under the 1993 surveillance case definition (given below). |

| ** | PGL = persistent generalized lymphadenopathy. Clinical Category A includes acute (primary) HIV infection. |

| # | See clinical categories below. |

| ## | See list of AIDS-defining conditions for 1993 definition below. |

| Table 2-4. World Health Organization Classification System for HIV Staging System | ||||||

|

|

Laboratory Component | Clinical Group | ||||

| CD4 Cell Count | Total Lymphocyte Count | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| A | ≥500 | ≥2000 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 |

| B | 200-499 | 1000-1999 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 |

| C | <200 | <1000 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

| Clinical Stage | Clinical History | Performance Scale Criteria | Propose Modifications | |||

|

One: Asymptomatic |

Asymptomatic infection |

Normal functional level in

performance scale |

none | |||

| Two Mild: Disease | Unintentional weight loss < 10% body weight Minor mucocutaneous manifestations (e.g., dermatitis, prurigo, fungal nail infections, angular cheilitis) Herpes zoster within previous 5 years Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections |

Performance Scale level at which symptoms, but nearly fully ambulatory | ||||

| Three: Moderate Disease | Unintentional weight loss > 10% body weight Chronic diarrhea > 1 month Prolonged fever > 1 month (constant or intermittent) Oral candidiasis Oral hairy leukoplakia Pulonary tuberculosis within the previous year Severe bacterial infections Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Performance Scale level at which in bed more than normal but < 50% of normal daytime during the previous month | ||||

Acute HIV infection is a transient symptomatic illness that can be identified in 40-90% of cases of new HIV infection. It is characterized by a high rate of HIV replication, high titers of virus in blood and lymphoid organs (up to several million copies of HIV RNA per mm3 of plasma), and initiation of an HIV-specific immune response. The amount of virus present in blood and tissues begins to fall after appearance of cytotoxic (killer) lymphocytes that specifically react with HIV antigens; the vigor of this response varies among individuals and is associated with subsequent rate of disease progression. (Cao, 1995) A pool of persistently infected CD4 cells (latent reservoirs) emerges early in the course of HIV infection and persists indefinitely. (Chun, 1998) Symptoms have been identified from 5-30 days after a recognized exposure to HIV. (Schacker, 1998) The signs and symptoms of acute HIV infection are not specific; fever, fatigue, rash, headache, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, mild gastrointestinal upset, night sweats, aseptic meningitis and oral ulcerations are most frequently reported. Because the clinical signs of acute HIV infection resemble those of many acute viral illnesses, the correct diagnosis is often missed. Because early treatment at the time of acute infection may be especially beneficial (See Chapter IV on Primary Medical Care), early suspicion of and evaluation for HIV infection should be encouraged. (Kahn, 1998)

Regardless of whether the syndrome of acute HIV infection is recognized or not, after the HIV-specific immunological response begins to control the intensity of viremia, a so-called viral set-point is established, which varies by individual. With exceedingly rare exceptions, the immunological response to HIV does not eliminate infection, but rather establishes a steady state between viral replication and elimination. (Henrad, 1995) A variable level of viremia is attained, which can be measured via quantification of the number of copies of HIV RNA present in blood (viral load). Although the viral load within the first 120 days of HIV infection is not of prognostic value (Schacker, 1998), in most patients a relatively stable viral load is attained after recovery from acute infection, and this viral set point is highly predictive of the rate of future progression of illness, at least as determined in studies that were largely focused on men. In the case of a high viral load set point (i.e. values ranging up from 40,000 copies per mm3) more rapid decline in CD4 cell counts and more rapid occurrence of Clinical Class B and C conditions will occur. Some individuals have viral load set points that are low (below 500 copies per mm3), which indicates a better prognosis; no evidence of progression (CD4 cell depletion or HIV-diseases) is seen for long periods of time in a small subset of patients (see section on long-term progression, below). The viral set point is likely influenced by several factors such as presence of other infections at the time of HIV exposure, genetic characteristics (particularly the type of HIV binding receptors present on lymphocytes) viral characteristics, age and perhaps gender (see below). (Kahn, 1998) During the period of clinical stability acute illnesses and other events that can stimulate the immune system, such as influenza, herpes simplex outbreaks, and tuberculosis as well as routine vaccinations, have been demonstrated to result in 10-1000 fold increases in viral load; these increases are transient and most often resolve within two months. (Stanley, 1996; Staprans, 1995) Thus, determination of viral load for prognostic purposes should not be done during or shortly after an acute illness.

For most HIV-infected persons, viral quasispecies evolve overtime. Transition for the non-syncytia-inducing macrophage-tropic viral strains, that are commonly present after transmission to syncytia-inducing T-lymphocyte tropic strains occurs in many hosts. While variation of viral quasispecies with time is usual, the mechanism by which this process occurs has not been defined. However, transitions in viral quasispecies and cellular tropism has been observed to coincide with key clinical events such as CD4 cell depletion and development of symptomatic illness. These virologic changes may reflect evolution of a virus that is tailored to an individuals immune response or other genetic characteristics. Interventions that prevent evolution of quasispecies in a host may yield effective therapies in the future. The HIV RNA level in tissues does not correlate in a linear fashion with blood levels, so even in patients with undetectable plasma HIV RNA, intracellular and tissue HIV RNA can still be detected with more sophisticated techniques. (Hockett, 1999) Thus HIV replication continues at varying pace among infected persons, even those who can control viremia well. HIV is also frequently present in the genital tract (Fiore, 1999; Iverson, 1998), where expression of inflammatory mediators, and lymphocyte receptors differ from blood and may influence the rate of viral replication and numbers of virions present. (Anderson, 1998; Hladik, 1999) While the quantities of HIV present in cervicovaginal fluid are generally similar to blood (Hart, 1999; Shaheen, 1999), they differ in some individuals. The finding that HIV isolates from the lower genital tract can have different genotypic markers than blood isolates from a single host (DiStefano 1999; Shaheen, 1999), supports the concept that the lower genital tract sometimes functions as a separate virologic compartment.In most studies of seroconverters, (persons for whom the date of the HIV infection can be estimated), 5060% of adults will be diagnosed with an AIDS-defining condition within 10 years of infection (for the pre-HAART treatment era). Forty-eight percent of seroconverters die (due to any cause) after 10 years of infection. Increasing age is the factor most consistently associated with rate of progression and death in most groups of patients studied to date. (Alioum, 1998; UK Register of HIV Seroconverters Steering Committee, 1998; Pezzott, 1999; Prins, 1999) Date of infection also influences time from infection to an AIDS diagnosis, at least in some locations, demonstrating that even in the pre-HAART era, improvements in treatment resulted in tangible benefits. (Webber, 1998)

A large number of laboratory tests have been evaluated as prognostic indicators in HIV infection. For the most part the tests can be divided into three groups: A. measures of HIV replication, B. measures of immune function and C. measures of inflammation. Group A is specific to HIV infection, Group B, when indicating severe CD4 cell depletion is relatively specific to HIV infection and Group C are generally not specific to HIV infection. Table 2-5, on the following page, summarizes these laboratory measures, outcomes, their advantages and disadvantages. HIV RNA quantitation performed on fresh or fresh-frozen plasma or serum, is a powerful and accurate prognostic indicator in HIV infection and is uniquely useful in determining response to antiretroviral therapy. (Saag, 1996) In general the best measures of prognosis and staging include combinations of HIV RNA level, CD4 cell count and perhaps lymphocyte function (cytotoxic lymphocyte response to HIV). (Spijkerman, 1997; Vlahov, 1998)

In untreated adults the median time from HIV infection to AIDS in developed countries is 8- 10 years. However, approximately 8-15% of HIV infected persons (most studies focus on men) remain symptom free for much longer periods of time, a phenomenon that has been named long-term survival (LTS). Among these individuals who remain clinically stable without treatment for 5-8 years, two groups can be discerned, those who have stable CD4 cell counts and those who have low CD4 cell counts, but no AIDS defining conditions. (Schrager 1994) Several factors have been found to be associated with long-term survival including host characteristics such as the presence of specific anti-HIV cytotoxic lympho- cyte responses, and viral characteristics such as defective genes and gene products. (Kirchhoff, 1995) LTS patients tend to have consistently lower levels of HIV RNA after the period of acute infection suggesting better control of viral replication. (Vesanen, 1996) For example viral growth in peripheral mononuclear cells taken from LTS was markedly less than in PBMCs taken from healthy HIV-uninfected donors. (Cao, 1995)

In general the predictors of the rate of HIV-disease progression and survival among women are the same as in men. CD4 cell count depletion and higher HIV RNA level are strong predictors of progression and survival in women. (Anastos 1996b) Several recent reports, however, describe gender-based differences in HIV RNA level and in rate of CD4 cell depletion; women had HIV RNA levels that were 30-50% lower than men who had comparable CD4 cell counts. (Bush, 1996; Evans, 1997; Farzadegan, 1998) Similar results occurred when analysis was restricted to seroconverters or when HIV culture was used to quantify viremia rather than RNA assays. ()Lyles, 1998; Sterling, 1999) Intuitively, lower levels of circulating HIV RNA, which suggest lower steady state level of viremia, should be associ- ated with better outcome. However, the findings of several recent studies suggest that the lower HIV RNA level does not provide benefit to women. Women experienced more rapid CD4 cell depletion and faster progression to AIDS and death than men at similar HIV-RNA levels, even when race and age were taken into consideration. (Anastos, 1999a; Farzadegan 1998) Determination of the effect of gender on the rate of progression, time until occurrence of an AIDS defining condition and death is a complicated process. Unless the date of HIV infection can be established, duration of infection becomes a significant unknown factor in studies. In addition, particularly in developed countries, HIV-infected women and men differ by more than just their gender. Women tend to have lower income, be members of minority ethnic groups, have been born in Africa, have used injection drugs or cocaine, or to have a sexual partner who has done so, all of which are risk factors for poor health in general. In most studies women have shorter duration of infection prior to AIDS and death than men, but these differences tend to disappear when CD4 cell count and drug use are taken into consideration. (Alioum, 1998; UK Register of HIV Seronconverters Steering Committee, 1998; Pezzotti, 1999; Santoro-Lopes 1998) Several studies have reported an excess proportion of infections or deaths due to bacterial infection, often pneumonia (Feldman, 1999), among women compared with men. (Melnich, 1994; Weisser, 1998) A summary of factors that influence disease progression is shown in Table 2-6.

In countries that are able to provide highly affective antiretroviral treatments (HAART), HIV-associated morbidity and mortality have declined significantly. (Michales, 1998; Miller, 1999a; Miller 1999b; Palella, 1998; Pezotti, 1999) (See Primary Medical Care in Chapter IV for more information). These population findings, based on regional surveillance systems, were preceded by a multitude of clinical trials that demonstrated clinical and virologic benefits of HAART. (Bartlett, 1996; Collier, 1996; Deeks, 1997; Hammer, 1997) Despite the promise and documented benefits of HAART clinical progression continues to occur among recipients, particularly among persons who received antiretroviral treatment prior to initiation of HAART. (Ledergerber, 1999) Viral resistance to HAART components can occur via several mechanisms, which for the most part involve mutation of viral target proteins. (Richman, 1996; Schapiro, 1999) The emergence of antiretroviral resistance is a function of several factors: prior treatment, pre-treatment level of viremia drug levels (adherence to medication regimens, bioavailability of medications, adequate dosing) and specifics of the regimen. (Guilick, 1998; Ledergerber, 1999; Shafer, 1998) Multiple daily doses, side effects and in some cases, dietary restrictions aggravate the problem of achieving optimal drug levels since protease inhibitor agents are relatively poorly bioavailable. Suppression of viral replication and prevention of resistance are directly related to level of antiretroviral drug. Persistent viral replication provides opportunity of occurrence of resistance mutations, and selective pressure to support continued presence of such mutants. (Condra, 1998; Feinberg, 1997; Wong, 1997) Besides clinical treatment failure, emergence of antiretroviral resistance is now associated with transmission of resistant virus to previously uninfected persons, a finding that could portend significant limits to the effectiveness of these treatments in populations over long periods of time. (Boden, 1999; Brodine, 1999; Yerly, 1999)

The high cost of antiretroviral drugs and the need for clinical and laboratory services for monitoring response to and efficacy of these treatments has greatly restricted provision of HAART in the developing world. Thus the reductions in morbidity and gains in survival in HIV patients that have been demonstrated in many industrialized countries do not extend to developing countries in which the majority of HIV cases worldwide occur. A consensus statement regarding provision of these therapies has been released based on meetings held in Dakar and Abidjan during 1997. The key recommendations of conference participants include: efforts must be made to expand provision of ART, ART only makes sense in the setting of effective AIDS control programs, funding must be sustained to provide uninterrupted treatment and continuity of care, care providers must be trained in use of the treatments and basic patient rights resources for assessment of efficacy and tolerance must be available, sentinel monitoring for resistance pattern determination should be available, 3-drug combination regimens should be used when possible, treatment of pregnant women to prevent perinatal transmission must be a priority, and new drug development should focus on less costly medications. (International AIDS Society, 1999)

The HIV/AIDS epidemic continues to spread without full control in any country. Over forty million people have been infected worldwide. By the end of 1998, the United Nations Program on AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that 33.4 million people were living with HIV, a figure which includes 13.8 million adult women (UNAIDS, 1998) (Table 1-1, page 2). In 1998 it is estimated that 5.8 million new HIV infections occurred of with 2.1 million of these occurring in women. After steady increases of the prevalence of disease among women during the 1990s, currently 43% of all persons over the age of 15 years living with HIV are women. Globally, AIDS is now the fourth leading cause of mortality; 2.5 million deaths have been attributable to AIDS, of which 900,000 occurred in women. The notable improvements in AIDS mortality reported in North America and Europe, in association with the introduction of highly active combination antiretroviral therapies, do not extend to most of the worlds cases which occur in regions in which this expensive type of treatment is not available. More than 95% of HIV-infected people live in the developing world, most in Sub-Saharan Africa. Seventy percent of infections that occurred during 1998 took place in this epicenter. The region has also experienced 83% of all AIDS deaths. Unfortunately prior projections of the epidemic course in Southern Africa underestimated the incidence of infection by half. (Balter, 1998) Improved data have revealed that the prevalence rates in southern Africa are staggering: 20-26% of adults (aged 15-49 years) are infected; in some regions 20-50% of pregnant women are infected and are likely to transmit infection to 1/3 of their offspring. The declining mortality rate, and population growth taking place in other regions cannot be extended to Sub-Saharan Africa, due to the extent of AIDS mortality. (Bongaarts 1998) AIDS has now surpassed malaria as the leading cause of death in this region. (Balter, 1999) Life expectancy will fall from 64 to 47 years by 2015. AIDS will cost, on an average, 17 years of life expectancy in the 9 Sub-Saharan countries with a > 10% prevalence of HIV infection among adults. The child mortality rates in this region are also elevated by AIDS; rates are approximately double that expected without the HIV epidemic. (UNAIDS, 1998) Within one year 2,400 Zimbabweans will succumb to AIDS per week, many in the prime of life, many leaving dependent children as orphans (up to 1 in 5 children are likely to become orphans). The United States Surgeon General, David Satcher, notes that the progress of decades of work immunizing children, controlling diseases, and improving nutrition is being negated by HIV. (Satcher, 1999) In Asia, the epidemic has a mixed pattern that includes countries with slow growth in HIV prevalence, countries with some success in control efforts and regions that appear to be experiencing explosive epidemics. Currently 7 million Asians are infected with HIV. Rapidly accelerating epidemics are possible in China, Cambodia, Vietnam and India. While urban areas were initially of greatest concern in many countries, recent information has revealed very active epidemics in specific rural areas (up to 2% of the general population), which are hosts to large proportions of the regions population.

While the outlook for AIDS in Asia is bleak, there is also cause for hope. Growth of the epidemic in the Philippines is notably slow. (Jacobs, 1999) Thailand has been successful in reducing the incidence of infection in sentinel population groups (such as members of the military and pregnant women) using a combination of good surveillance effective policy response, implementation of educational and condom promotion programs. The incidence of HIV infection among pregnant women in Thailand has dropped from a peak of 2.4% in 1995 to 1.7% in 1997. (Phoolchareon 1998) However ongoing political upheaval and cuts to the national HIV prevention budget may modify this pattern of success in the near future. In the Americas the epidemic continues to grow in specific subgroups. In the United States, as summarized earlier in this chapter, the highest incidence of infection is occurring among poor women, particularly among women of color. In Mexico the incidence of infection among men who have sex with men continues high, while in Brazil and the Caribbean heterosexual transmission is increasing. At surveillance sites in the Dominican Republic and Haiti the prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women has reached 8%. (UNAIDS, 1998) Rapid spread of infection among injection drug users in Eastern Europe and Central Asia likely to foreshadow a large number of cases among women and increasing prevalence of perinatal transmission. The introduction of HIV into these high-risk populations has been paralleled by tremendous increases in the incidence of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. (Gollub, 1999)Control of the HIV epidemic should be a worldwide health priority. Complex interactions of social, economic and cultural factors have preceded AIDS with epidemics of other sexually transmitted diseases, and now hinder control of HIV itself. Global disparities in economic status have limited efforts to control sexually transmitted diseases that are much simpler to diagnose and treat than HIV. The effect of limited monetary resources are compounded by stigmatization of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases that effect willingness to seek care, social support of afflicted individuals and health policy decision making. Traditional cultural values regarding the role of women also tends to intensify the problems. Lack of acceptance of the right of women to make decisions about child bearing and work outside the home limit options for individuals who wish to reduce risk of infection via sexual exposures. Economic independence is a crucial factor enabling women to make some decisions themselves. The options for employment outside of sex work, for divorced or widowed women, in many societies are quite restricted. These fundamental values may directly conflict with efforts to empower women to avoid risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

To control the HIV epidemic, societies need to make deep commitments that may require an uncomfortable loss of highly valued cultural norms. Without social acceptance and encouragement, behaviorally mediated risk reduction strategies may not assume full efficacy. Vaccination is, at present, an optimal but unavailable solution. The prospects for development of an effective vaccine in the near future are not promising. Thus we have good cause to fear for the effects of HIV on women worldwide, and to increase our attention to this enormous problem as we enter the twenty-first century and the third decade of the HIV pandemic. Source: Ruth M. Greenblat, MD Nancy A. Hessel, MSPH U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Service Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau.

HIV infection among U.S. women has increased significantly over the last decade, especially in communities of color. CDC estimates that, in the United States, between 120,000 and 160,000 adult and adolescent females are living with HIV infection, including those with AIDS.

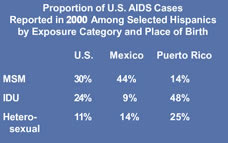

Between 1992 and 1998, the number of persons living with AIDS increased in all groups, as a result of the 1993 expanded AIDS case definition and, more recently, improved survival among those who have benefited from the new combination drug therapies. During that 6-year period, a growing proportion of women were living with AIDS, reflecting the ongoing shift in populations affected by the epidemic. In 1992, women accounted for 14% of persons living with AIDS–by 1998, the proportion had grown to 20%. In just over a decade, the proportion of all AIDS cases reported among adult and adolescent women more than tripled from 7% in 1985 to 23% in 1999. The epidemic has increased most dramatically among women of color. African American and Hispanic women together represent less than one-fourth of all U.S. women, yet they account for more than three-fourths (77%) of AIDS cases reported to date among women in our country. In 1999 alone (see chart above), women of color represented an even higher proportion of cases. While AIDS-related deaths among women were decreasing as of 1998, largely as a result of recent advances in HIV treatment, HIV/AIDS remains among the leading causes of death for U.S. women aged 25-44. And among African American women in this same age group, AIDS was the third leading case of death in 1998.Sex with drug users plays large role In 1999 most women(40%)reported with AIDS were infected through heterosexual exposure to HIV, injection drug use accounted for 27%. In addition to the direct risks associated with drug injection (sharing needles), drug use also is fueling the heterosexual spread of the epidemic. A large proportion of women infected heterosexually were infected through sex with an injection drug user. Reducing the toll of the epidemic among women will require efforts to combat substance abuse, in addition to reducing HIV risk behaviors.

Many HIV/AIDS cases among women in the United States are initially reported without risk information, suggesting that women may be unaware of their partners' risk factors or that healthcare providers are not documenting their risk. Historically, more than two-thirds of AIDS cases among women initially reported without identified risk were later reclassified as heterosexual transmission, and just over one-fourth were attributed to injection drug use.

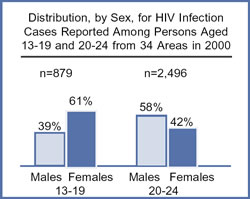

| Pay attention to prevention for women. The AIDS epidemic is far from over. Scientists believe that cases of HIV infection reported among 13- to 24-year-olds are indicative of overall trends in HIV incidence (the number of new infections in a given time period, usually a year) because this age group has more recently initiated high-risk behaviors–and females made up nearly half (49%) of HIV cases in this age group reported from the 32 areas with confidential HIV | |

| reporting for adults and adolescents in 1999. Further, for all years combined, young African American and Hispanic women account for more than three-fourths of HIV infections reported among females between the ages of 13 and 24 in these areas. | |

| Implement programs that have been proven effective in changing risky behaviors among women and sustaining those changes over time, maintaining a focus on both the uninfected and infected populations of women. | |

| Increase emphasis on prevention and treatment services for young women and women of color. Knowledge about preventive behaviors and awareness of the need to practice them is critical for each and every generation of young women–prevention programs should be comprehensive and should include participation by parents as well as the educational system. Community-based programs must reach out-of-school youth in such settings as youth detention centers and shelters for runaways. | |

| Address the intersection of drug use and sexual HIV transmission. Women are at risk of acquiring HIV sexually from a partner who injects drugs and from sharing needles themselves. Additionally, women who use noninjection drugs (e.g., crack cocaine, methamphetamines) are at greater risk of acquiring HIV sexually, especially if they trade sex for drugs or money. | |

| Develop and widely disseminate effective female-controlled prevention methods. More options are urgently needed for women who are unwilling or unable to negotiate condom use with a male partner. CDC is collaborating with scientists around the world to evaluate the prevention effectiveness of the female condom and to research and develop topical microbicides that can kill HIV and the pathogens that cause STDs. | |

| Better integrate prevention and treatment services for women across the board, including the prevention and treatment of other STDs and substance abuse and access to antiretroviral therapy. |

In the United States, the impact of HIV and AIDS in the African American community has been devastating. Through

December 1999, CDC had received reports of 733,374 AIDS cases - of those, 272,881 cases occurred among African

Americans. Representing only an estimated 12% of the total U.S. population, African Americans make up almost 37% of all

AIDS cases reported in this country.

In the United States, the impact of HIV and AIDS in the African American community has been devastating. Through

December 1999, CDC had received reports of 733,374 AIDS cases - of those, 272,881 cases occurred among African

Americans. Representing only an estimated 12% of the total U.S. population, African Americans make up almost 37% of all

AIDS cases reported in this country.

21,900 cases were reported among African Americans, representing nearly half (47%) of the 46,400 AIDS cases reported that year.

Almost two-thirds (63%) of all women reported with AIDS were African American. African American children also represented almost two-thirds (65%) of all reported pediatric AIDS cases. The 1999 rate of reported AIDS cases among African Americans was 66.0 per 100,000 population, more than 2 times greater than the rate for Hispanics and 8 times greater than the rate for whites. Data on HIV and AIDS diagnoses in 25 states with integrated reporting systems show these trends are continuing. In these states, during the period from January 1996 through June 1999, African Americans represented a high proportion (50%) of all AIDS diagnoses, but an even greater proportion (57%) of all HIV diagnoses. And among young people (ages 13 to 24), 65% of the HIV diagnoses were among African Americans.

|

Adult/Adolescent Men. Among African American men with AIDS, men who have sex with men (MSM) represent the largest proportion (37%) of reported cases since the epidemic began. The second most common exposure category for African American men is injection drug use (34%), and heterosexual exposure accounts for 8% of cumulative cases.

Adult/Adolescent Women. Among African American women, injection drug use has accounted for 42% of all AIDS case reports since the epidemic began, with 38% due to heterosexual contact.

Looking at select seroprevalence studies among high-risk populations gives an even clearer picture of why the epidemic continues to spread in communities of color. The data suggest that three interrelated issues play a role–the continued health disparities between economic classes, the challenges related to controlling substance abuse, and the intersection of substance abuse with the epidemic of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).