3.

Drug Addiction

Treatment

v Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment

Preface

Drug addiction is a complex illness. It is characterized by compulsive, at times uncontrollable drug craving, seeking, and use that persist even in the face of extremely negative consequences. For many people, drug addiction becomes chronic, with relapses possible even after long periods of abstinence.

The path to drug addiction begins with the act of taking drugs. Over time, a person's ability to choose not to take drugs can be compromised. Drug seeking becomes compulsive, in large part as a result of the effects of prolonged drug use on brain functioning and, thus, on behavior.

The compulsion to use drugs can take over the individual's life. Addiction often involves not only compulsive drug taking but also a wide range of dysfunctional behaviors that can interfere with normal functioning in the family, the workplace, and the broader community. Addiction also can place people at increased risk for a wide variety of other illnesses. These illnesses can be brought on by behaviors, such as poor living and health habits, that often accompany life as an addict, or because of toxic effects of the drugs themselves.

Because addiction has so many dimensions and disrupts so many aspects of an individual's life, treatment for this illness is never simple. Drug treatment must help the individual stop using drugs and maintain a drug-free life-style, while achieving productive functioning in the family, at work, and in society. Effective drug abuse and addiction treatment programs typically incorporate many components, each directed to a particular aspect of the illness and its consequences.

Three decades of scientific research and clinical practice have yielded a variety of effective approaches to drug addiction treatment. Extensive data document that drug addiction treatment is as effective as are treatments for most other similarly chronic medical conditions. In spite of scientific evidence that establishes the effectiveness of drug abuse treatment, many people believe that treatment is ineffective. In part, this is because of unrealistic expectations. Many people equate addiction with simply using drugs and therefore expect that addiction should be cured quickly, and if it is not, treatment is a failure. In reality, because addiction is a chronic disorder, the ultimate goal of long-term abstinence often requires sustained and repeated treatment episodes.

Of course, not all drug abuse treatment is equally effective. Research also has revealed a set of overarching principles that characterize the most effective drug abuse and addiction treatments and their implementation.

Principles of Effective Treatment

1. No single treatment is appropriate for all individuals. Matching treatment settings, interventions, and services to each individual's particular problems and needs is critical to his or her ultimate success in returning to productive functioning in the family, workplace, and society.

2. Treatment needs to be readily available. Because individuals who are addicted to drugs may be uncertain about entering treatment, taking advantage of opportunities when they are ready for treatment is crucial. Potential treatment applicants can be lost if treatment is not immediately available or is not readily accessible.

3. Effective treatment attends to multiple needs of the individual, not just his or her drug use. To be effective, treatment must address the individual's drug use and any associated medical, psychological, social, vocational, and legal problems.

4. An individual's treatment and services plan must be assessed continually and modified as necessary to ensure that the plan meets the person's changing needs. A patient may require varying combinations of services and treatment components during the course of treatment and recovery. In addition to counseling or psychotherapy, a patient at times may require medication, other medical services, family therapy, parenting instruction, vocational rehabilitation, and social and legal services. It is critical that the treatment approach be appropriate to the individual's age, gender, ethnicity, and culture.

5. Remaining in treatment for an adequate period of time is critical for treatment effectiveness. The appropriate duration for an individual depends on his or her problems and needs. Research indicates that for most patients, the threshold of significant improvement is reached at about 3 months in treatment. After this threshold is reached, additional treatment can produce further progress toward recovery. Because people often leave treatment prematurely, programs should include strategies to engage and keep patients in treatment.

6. Counseling (individual and/or group) and other behavioral therapies are critical components of effective treatment for addiction. In therapy, patients address issues of motivation, build skills to resist drug use, replace drug-using activities with constructive and rewarding non-drug-using activities, and improve problem-solving abilities. Behavioral therapy also facilitates interpersonal relationships and the individual's ability to function in the family and community.

7. Medications are an important element of treatment for many patients, especially when combined with counseling and other behavioral therapies. Methadone and levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) are very effective in helping individuals addicted to heroin or other opiates stabilize their lives and reduce their illicit drug use. Naltrexone is also an effective medication for some opiate addicts and some patients with co-occurring alcohol dependence. For persons addicted to nicotine, a nicotine replacement product (such as patches or gum) or an oral medication (such as bupropion) can be an effective component of treatment. For patients with mental disorders, both behavioral treatments and medications can be critically important.

8. Addicted or drug-abusing individuals with coexisting mental disorders should have both disorders treated in an integrated way. Because addictive disorders and mental disorders often occur in the same individual, patients presenting for either condition should be assessed and treated for the co-occurrence of the other type of disorder.

9. Medical detoxification is only the first stage of addiction treatment and by itself does little to change long-term drug use. Medical detoxification safely manages the acute physical symptoms of withdrawal associated with stopping drug use. While detoxification alone is rarely sufficient to help addicts achieve long-term abstinence, for some individuals it is a strongly indicated precursor to effective drug addiction treatment.

10. Treatment does not need to be voluntary to be effective. Strong motivation can facilitate the treatment process. Sanctions or enticements in the family, employment setting, or criminal justice system can increase significantly both treatment entry and retention rates and the success of drug treatment interventions.

11. Possible drug use during treatment must be monitored continuously. Lapses to drug use can occur during treatment. The objective monitoring of a patient's drug and alcohol use during treatment, such as through urinalysis or other tests, can help the patient withstand urges to use drugs. Such monitoring also can provide early evidence of drug use so that the individual's treatment plan can be adjusted. Feedback to patients who test positive for illicit drug use is an important element of monitoring.

12. Treatment programs should provide assessment for HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, and counseling to help patients modify or change behaviors that place themselves or others at risk of infection. Counseling can help patients avoid high-risk behavior. Counseling also can help people who are already infected manage their illness.

13. Recovery from drug addiction can be a long-term process and frequently requires multiple episodes of treatment. As with other chronic illnesses, relapses to drug use can occur during or after successful treatment episodes. Addicted individuals may require prolonged treatment and multiple episodes of treatment to achieve long-term abstinence and fully restored functioning. Participation in self-help support programs during and following treatment often is helpful in maintaining abstinence.

Reviewers

Martin W. Adler, Ph.D.

Temple University School of Medicine

Andrea G. Barthwell, M.D.

Encounter

Medical Group

Lawrence S. Brown, Jr., M.D., M.P.H.

Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation

James

F. Callahan, D.P.A.

American Society of Addiction Medicine

H. Westley Clark, M.D., J.D.,

M.P.H., CAS, FASAM

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

Richard R. Clayton, Ph.D.

University

of Kentucky

Linda B. Cottler, Ph.D.

Washington University School of Medicine

David P.

Friedman, Ph.D.

Bowman Gray School of Medicine Reese T. Jones, M.D.

University of California

at San Francisco

Linda R. Wolf-Jones, D.S.W.

Therapeutic Communities of America

Linda Kaplan,

CAE

National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors

A. Thomas McLellan, Ph.D.

University

of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

G. Alan Marlatt, Ph.D.

University of Washington

Nancy K.

Mello, Ph.D.

Harvard Medical School

Charles P. O'Brien, M.D., Ph.D.

University of

Pennsylvania

Eric J. Simon, Ph.D.

New York University Medical Center

George Woody, M.D.

Philadelphia

VA Medical Center

University of Pennsylvania

Resources

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Inquiries about NIDA's treatment research activities: Division of Treatment Research and Development (301) 443-6173 (for questions regarding behavioral therapies and medications) or Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Research (301) 443-4060 (for questions regarding access to treatment, organization, management, financing, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness).

Website: http://www.nida.nih.gov

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT)

CSAT, a part of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, is responsible for supporting treatment services through block grants and developing knowledge about effective drug treatment, disseminating the findings to the field, and promoting their adoption. CSAT also operates the National Treatment Referral 24-hour Hotline (1-800-662-HELP) which offers information and referral to people seeking treatment programs and other assistance. CSAT publications are available through the National Clearinghouse on Alcohol and Drug Information (1-800-729-6686). Additional information about CSAT can be found on their website at http://www.samhsa.gov/csat.

Selected NIDA Educational Resources on Drug Addiction Treatment

The following are available from the National Clearinghouse on Alcohol and Drug Information (NCADI), the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), or the Government Printing Office (GPO). To order, refer to the NCADI (1-800-729-6686), NTIS (1-800-553-6847), or GPO (202-512-1800) number provided with the resource description.

Manuals and Clinical Reports

Measuring and Improving Cost, Cost-Effectiveness, and Cost-Benefit for Substance Abuse Treatment Programs (1999). Offers substance abuse treatment program managers tools with which to calculate the costs of their programs and investigate the relationship between those costs and treatment outcomes. NCADI # BKD340. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/IMPCOST/IMPCOSTIndex.html.

A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction (1998). This is the first in NIDA's "Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction" series. Describes cognitive-behavioral therapy, a short-term focused approach to helping cocaine-addicted individuals become abstinent from cocaine and other drugs. NCADI # BKD254. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/TXManuals/CBT/CBT1.html.

A Community Reinforcement Plus Vouchers Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction (1998). This is the second in NIDA's "Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction" series. This treatment integrates a community reinforcement approach with an incentive program that uses vouchers. NCADI # BKD255. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/TXManuals/CRA/CRA1.html.

An Individual Drug Counseling Approach to Treat Cocaine Addiction: The Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study Model (1999). This is the third in NIDA's "Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction" series. Describes specific cognitive-behavioral models that can be implemented in a wide range of differing drug abuse treatment settings. NCADI # BKD337. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/TXManuals/IDCA/IDCA1.html.

Mental Health Assessment and Diagnosis of Substance Abusers: Clinical Report Series (1994). Provides detailed descriptions of psychiatric disorders that can occur among drug-abusing clients. NCADI # BKD148. Relapse Prevention: Clinical Report Series (1994). Discusses several major issues to relapse prevention. Provides an overview of factors and experiences that can lead to relapse. Reviews general strategies for preventing relapses, and describes four specific approaches in detail. Outlines administrative issues related to implementing a relapse prevention program. NCADI # BKD147.

Addiction Severity Index Package (1993). Provides a structured clinical interview designed to collect information about substance use and functioning in life areas from adult clients seeking drug abuse treatment. Includes a handbook for program administrators, a resource manual, two videotapes, and a training facilitator's manual. NTIS # AVA19615VNB2KUS. $150.

Program Evaluation Package (1993). A practical resource for treatment program administrators and key staff. Includes an overview and case study manual, a guide for evaluation, a resource guide, and a pamphlet. NTIS # 95-167268/BDL. $86.50.

Relapse Prevention Package (1993). Examines two effective relapse prevention models, the Recovery Training and Self-Help (RTSH) program and the Cue Extinction model. NTIS # 95-167250/BDL. $189; GPO # 017-024-01555-5. $57. (Sold by GPO as a set of 7 books)

Research Monographs

Beyond the Therapeutic Alliance: Keeping the Drug-Dependent Individual in Treatment (Research Monograph 165) (1997) . Reviews current treatment research on the best ways to retain patients in drug abuse treatment. NTIS # 97-181606. $47; GPO # 017-024-01608-0. $17. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph165/download165.html.

Treatment of Drug-Exposed Women and Children: Advances in Research Methodology (Research Monograph 166) (1997) . Presents experiences, products, and procedures of NIDA-supported Treatment Research Demonstration Program projects. NCADI # M166; NTIS # 96-179106. $75; GPO # 017-01592-0. $13. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph166/download.html.

Treatment of Drug-Dependent Individuals With Comorbid Mental Disorders (Research Monograph 172) (1997). Promotes effective treatment by reporting state-of-the-art treatment research on individuals with comorbid mental and addictive disorders and research on HIV-related issues among people with comorbid conditions. NCADI # M172; NTIS # 97-181580. $41; GPO # 017-024-01605. $10. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph172/download172.html

Medications Development for the Treatment of Cocaine Dependence: Issues in Clinical Efficacy Trials (Research Monograph 175) (1998). A state-of-the-art handbook for clinical investigators, pharmaceutical scientists, and treatment researchers. NCADI # M175. Available online at http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph175/download175.html

Videos

Adolescent Treatment Approaches (1991). Emphasizes the importance of pinpointing and addressing individual problem areas, such as sexual abuse, peer pressure, and family involvement in treatment. Running time: 25 min. NCADI # VHS40. $12.50.

NIDA Technology Transfer Series: Assessment (1991). Shows how to use a number of diagnostic instruments as well as how to assess the implementation and effectiveness of the plan during various phases of the patient's treatment. Running time: 22 min. NCADI # VHS38. $12.50.

Drug Abuse Treatment in Prison: A New Way Out (1995). Portrays two comprehensive drug abuse treatment approaches that have been effective with men and women in State and Federal Prisons. Running time: 23 min. NCADI # VHS72. $12.50.

Dual Diagnosis (1993). Focuses on the problem of mental illness in drug-abusing and drug-addicted populations, and examines various approaches useful for treating dual-diagnosed clients. Running time: 27 min. NCADI # VHS58. $12.50.

LAAM: Another Option for Maintenance Treatment of Opiate Addiction (1995). Shows how LAAM can be used to meet the opiate treatment needs of individual clients from the provider and patient perspectives. Running time: 16 min. NCADI # VHS73. $12.50.

Methadone: Where We Are (1993). Examines issues such as the use and effectiveness of methadone as a treatment, biological effects of methadone, the role of the counselor in treatment, and societal attitudes toward methadone treatment and patients. Running time: 24 min. NCADI # VHS59. $12.50.

Relapse Prevention (1991). Helps practitioners understand the common phenomenon of relapse to drug use among patients in treatment. Running time: 24 min. NCADI # VHS37. $12.50.

Treatment Issues for Women (1991). Assists treatment counselors help female patients to explore relationships with their children, with men, and with other women. Running time: 22 min. NCADI # VHS39. $12.50.

Treatment Solutions (1999). Describes the latest developments in treatment research and emphasizes the benefits of drug abuse treatment, not only to the patient, but also to the greater community. Running time: 19 min. NCADI # DD110. $12.50.

Program Evaluation Package (1993). A practical resource for treatment program administrators and key staff. Includes an overview and case study manual, a guide for evaluation, a resource guide, and a pamphlet. NTIS # 95-167268/BDL. $86.50.

Relapse Prevention Package (1993). Examines two effective relapse prevention models, the Recovery Training and Self-Help (RTSH) program and the Cue Extinction model. NTIS # 95-167250. $189; GPO # 017-024-01555-5. $57. (Sold by GPO as a set of 7 books)

Other Federal Resources

The National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information (NCADI). NIDA publications and treatment materials along with publications from other Federal agencies are available from this information source. Staff provide assistance in English and Spanish, and have TDD capability. Phone: 1-800-729-6686. Website: http://www.health.org.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ). As the research agency of the Department of Justice, NIJ supports research, evaluation, and demonstration programs relating to drug abuse in the contexts of crime and the criminal justice system. For information, including a wealth of publications, contact the National Criminal Justice Reference Service by telephone (1-800-851-3420 or 1-301-519-5500) or on the World Wide Web (http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij).

v Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is drug addiction treatment?

There are many addictive drugs, and treatments for specific drugs can differ. Treatment also varies depending on the characteristics of the patient.

Problems associated with an individual's drug addiction can vary significantly. People who are addicted to drugs come from all walks of life. Many suffer from mental health, occupational, health, or social problems that make their addictive disorders much more difficult to treat. Even if there are few associated problems, the severity of addiction itself ranges widely among people.

A variety of scientifically based approaches to drug addiction treatment exists. Drug addiction treatment can include behavioral therapy (such as counseling, cognitive therapy, or psychotherapy), medications, or their combination. Behavioral therapies offer people strategies for coping with their drug cravings, teach them ways to avoid drugs and prevent relapse, and help them deal with relapse if it occurs. When a person's drug-related behavior places him or her at higher risk for AIDS or other infectious diseases, behavioral therapies can help to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Case management and referral to other medical, psychological, and social services are crucial components of treatment for many patients. The best programs provide a combination of therapies and other services to meet the needs of the individual patient, which are shaped by such issues as age, race, culture, sexual orientation, gender, pregnancy, parenting, housing, and employment, as well as physical and sexual abuse.

Treatment medications, such as methadone, LAAM, and naltrexone, are available for individuals addicted to opiates. Nicotine preparations (patches, gum, nasal spray) and bupropion are available for individuals addicted to nicotine.

The best treatment programs provide a combination of therapies and other services to meet the needs of the individual patient.

Medications, such as antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or neuroleptics, may be critical for treatment success when patients have co-occurring mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, or psychosis.

Treatment can occur in a variety of settings, in many different forms, and for different lengths of time. Because drug addiction is typically a chronic disorder characterized by occasional relapses, a short-term, onetime treatment often is not sufficient. For many, treatment is a long-term process that involves multiple interventions and attempts at abstinence.

Components of Comprehensive Drug Abuse Treatment

The best treatment programs provide a combination of therapies and other services to meet the needs of the individual patient.

2. Why can't drug addicts quit on their own?

Nearly all addicted individuals believe in the beginning that they can stop using drugs on their own, and most try to stop without treatment. However, most of these attempts result in failure to achieve long-term abstinence. Research has shown that long-term drug use results in significant changes in brain function that persist long after the individual stops using drugs. These drug-induced changes in brain function may have many behavioral consequences, including the compulsion to use drugs despite adverse consequences.

Understanding that addiction has such an

important biological component may help explain an individual's difficulty in achieving and

maintaining abstinence without treatment. Psychological stress from work or family problems, social

cues (such as meeting individuals from one's drug-using past), or the environment (such as

encountering streets, objects, or even smells associated with drug use) can interact with biological

factors to hinder attainment of sustained abstinence and make relapse more likely. Research studies

indicate that even the most severely addicted individuals can participate actively in treatment and

that active participation is essential to good outcomes.

3. How effective is drug addiction treatment?

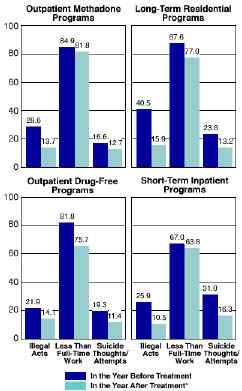

In addition to stopping drug use, the goal of treatment is to return the individual to productive functioning in the family, workplace, and community. Measures of effectiveness typically include levels of criminal behavior, family functioning, employability, and medical condition. Overall, treatment of addiction is as successful as treatment of other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma.

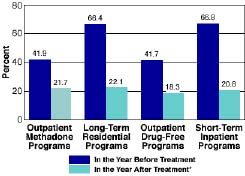

According to several studies, drug treatment reduces drug use by 40 to 60 percent and significantly decreases criminal activity during and after treatment. For example, a study of therapeutic community treatment for drug offenders demonstrated that arrests for violent and nonviolent criminal acts were reduced by 40 percent or more. Methadone treatment has been shown to decrease criminal behavior by as much as 50 percent. Research shows that drug addiction treatment reduces the risk of HIV infection and that interventions to prevent HIV are much less costly than treating HIV-related illnesses. Treatment can improve the prospects for employment, with gains of up to 40 percent after treatment.

Although these effectiveness rates hold in general, individual treatment outcomes depend on the extent and nature of the patient's presenting problems, the appropriateness of the treatment components and related services used to address those problems, and the degree of active engagement of the patient in the treatment process.

4. How long does drug addiction treatment usually last?

Individuals progress through drug addiction treatment at various speeds, so there is no predetermined length of treatment. However, research has shown unequivocally that good outcomes are contingent on adequate lengths of treatment. Generally, for residential or outpatient treatment, participation for less than 90 days is of limited or no effectiveness, and treatments lasting significantly longer often are indicated. For methadone maintenance, 12 months of treatment is the minimum, and some opiate-addicted individuals will continue to benefit from methadone maintenance treatment over a period of years.

Many people who enter treatment drop out before receiving all the benefits that treatment can provide. Successful outcomes may require more than one treatment experience. Many addicted individuals have multiple episodes of treatment, often with a cumulative impact.

5. What helps people stay in treatment?

Since successful outcomes often depend upon retaining the person long enough to gain the full benefits of treatment, strategies for keeping an individual in the program are critical. Whether a patient stays in treatment depends on factors associated with both the individual and the program. Individual factors related to engagement and retention include motivation to change drug-using behavior, degree of support from family and friends, and whether there is pressure to stay in treatment from the criminal justice system, child protection services, employers, or the family. Within the program, successful counselors are able to establish a positive, therapeutic relationship with the patient. The counselor should ensure that a treatment plan is established and followed so that the individual knows what to expect during treatment. Medical, psychiatric, and social services should be available.

Since some individual problems (such as serious mental illness, severe cocaine or crack use, and criminal involvement) increase the likelihood of a patient dropping out, intensive treatment with a range of components may be required to retain patients who have these problems. The provider then should ensure a transition to continuing care or "aftercare" following the patient's completion of formal treatment.

6. Is the use of medications like methadone simply replacing one drug addiction with another?

No. As used in maintenance treatment, methadone and LAAM are not heroin substitutes. They are safe and effective medications for opiate addiction that are administered by mouth in regular, fixed doses. Their pharmacological effects are markedly different from those of heroin.

Injected, snorted, or smoked heroin causes an almost immediate "rush" or brief period of euphoria that wears off very quickly, terminating in a "crash." The individual then experiences an intense craving to use more heroin to stop the crash and reinstate the euphoria. The cycle of euphoria, crash, and craving repeated several times a day leads to a cycle of addiction and behavioral disruption. These characteristics of heroin use result from the drug's rapid onset of action and its short duration of action in the brain. An individual who uses heroin multiple times per day subjects his or her brain and body to marked, rapid fluctuations as the opiate effects come and go. These fluctuations can disrupt a number of important bodily functions. Because heroin is illegal, addicted persons often become part of a volatile drug-using street culture characterized by hustling and crimes for profit.

Methadone and LAAM have far more gradual onsets of action than heroin and, as a result, patients stabilized on these medications do not experience any rush. In addition, both medications wear off much more slowly than heroin, so there is no sudden crash, and the brain and body are not exposed to the marked fluctuations seen with heroin use. Maintenance treatment with methadone or LAAM markedly reduces the desire for heroin. If an individual maintained on adequate, regular doses of methadone (once a day) or LAAM (several times per week) tries to take heroin, the euphoric effects of heroin will be significantly blocked. According to research, patients undergoing maintenance treatment do not suffer the medical abnormalities and behavioral destabilization that rapid fluctuations in drug levels cause in heroin addicts.

7. What role can the criminal justice system play in the treatment of drug addiction?

Increasingly, research is demonstrating that treatment for drug-addicted offenders during and after incarceration can have a significant beneficial effect upon future drug use, criminal behavior, and social functioning. The case for integrating drug addiction treatment approaches with the criminal justice system is compelling. Combining prison- and community-based treatment for drug-addicted offenders reduces the risk of both recidivism to drug-related criminal behavior and relapse to drug use. For example, a recent study found that prisoners who participated in a therapeutic treatment program in the Delaware State Prison and continued to receive treatment in a work-release program after prison were 70 percent less likely than nonparticipants to return to drug use and incur rearrested.

The majority of offenders involved with the criminal justice system are not in prison but are under community supervision. For those with known drug problems, drug addiction treatment may be recommended or mandated as a condition of probation. Research has demonstrated that individuals who enter treatment under legal pressure have outcomes as favorable as those who enter treatment voluntarily.

The criminal justice system refers drug offenders into treatment through a variety of mechanisms, such as diverting nonviolent offenders to treatment, stipulating treatment as a condition of probation or pretrial release, and convening specialized courts that handle cases for offenses involving drugs. Drug courts, another model, are dedicated to drug offender cases. They mandate and arrange for treatment as an alternative to incarceration, actively monitor progress in treatment, and arrange for other services to drug-involved offenders.

The most effective models integrate criminal justice and drug treatment systems and services. Treatment and criminal justice personnel work together on plans and implementation of screening, placement, testing, monitoring, and supervision, as well as on the systematic use of sanctions and rewards for drug abusers in the criminal justice system. Treatment for incarcerated drug abusers must include continuing care, monitoring, and supervision after release and during parole.

8. How does drug addiction treatment help reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases?

Many drug addicts, such as heroin or cocaine addicts and particularly injection drug users, are at increased risk for HIV/AIDS as well as other infectious diseases like hepatitis, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections. For these individuals and the community at large, drug addiction treatment is disease prevention.

Drug injectors who do not enter treatment are up to six times more likely to become infected with HIV than injectors who enter and remain in treatment. Drug users who enter and continue in treatment reduce activities that can spread disease, such as sharing injection equipment and engaging in unprotected sexual activity. Participation in treatment also presents opportunities for screening, counseling, and referral for additional services. The best drug abuse treatment programs provide HIV counseling and offer HIV testing to their patients.

9. Where do 12-Step or self-help programs fit into drug addiction treatment?

Self-help groups can complement and extend the effects of professional treatment. The most prominent self-help groups are those affiliated with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Cocaine Anonymous (CA), all of which are based on the 12-step model, and Smart Recoveryฎ. Most drug addiction treatment programs encourage patients to participate in a self-help group during and after formal treatment.

10. How can families and friends make a difference in the life of someone needing treatment?

Family and friends can play critical roles in motivating individuals with drug problems to enter and stay in treatment. Family therapy is important, especially for adolescents. Involvement of a family member in an individual's treatment program can strengthen and extend the benefits of the program.

11. Is drug addiction treatment worth its cost?

Drug addiction treatment is cost-effective in reducing drug use and its associated health and social costs. Treatment is less expensive than alternatives, such as not treating addicts or simply incarcerating addicts. For example, the average cost for 1 full year of methadone maintenance treatment is approximately $4,700 per patient, whereas 1 full year of imprisonment costs approximately $18,400 per person.

According to several conservative estimates, every $1 invested in addiction treatment programs yields a return of between $4 and $7 in reduced drug-related crime, criminal justice costs, and theft alone. When savings related to health care are included, total savings can exceed costs by a ratio of 12 to 1. Major savings to the individual and society also come from significant drops in interpersonal conflicts, improvements in workplace productivity, and reductions in drug-related accidents.

v Drug Addiction Treatment in the United States

Drug addiction is a complex disorder that can involve virtually every aspect of an individual's functioning in the family, at work, and in the community. Because of addiction's complexity and pervasive consequences, drug addiction treatment typically must involve many components. Some of those components focus directly on the individual's drug use. Others, like employment training, focus on restoring the addicted individual to productive membership in the family and society.

Treatment for drug abuse and addiction is delivered in many different settings, using a variety of behavioral and pharmacological approaches. In the United States, more than 11,000 specialized drug treatment facilities provide rehabilitation, counseling, behavioral therapy, medication, case management, and other types of services to persons with drug use disorders.

Because drug abuse and addiction are major public health problems, a large portion of drug treatment is funded by local, State, and Federal governments. Private and employer-subsidized health plans also may provide coverage for treatment of drug addiction and its medical consequences.

Drug abuse and addiction are treated in specialized treatment facilities and mental health clinics by a variety of providers, including certified drug abuse counselors, physicians, psychologists, nurses, and social workers. Treatment is delivered in outpatient, inpatient, and residential settings. Although specific treatment approaches often are associated with particular treatment settings, a variety of therapeutic interventions or services can be included in any given setting.

Behavioral Change Through Treatment

Recovery from the disease of drug addiction is often a long-term process, involving multiple relapses before a patient achieves prolonged abstinence. Many behavioral therapies have been shown to help patients achieve initial abstinence and maintain prolonged abstinence. One frequently used therapy is cognitive behavioral relapse prevention in which patients are taught new ways of acting and thinking that will help them stay off drugs. For example, patients are urged to avoid situations that lead to drug use and to practice drug refusal skills. They also are taught to think of the occasional relapse as a "slip" rather than as a failure. Cognitive behavioral relapse prevention has proven to be a useful and lasting therapy for many drug addicted individuals.

One of the more well-developed behavioral techniques in drug abuse treatment is contingency management, a system of rewards and punishments to make abstinence attractive and drug use unattractive. Ultimately, the aim of contingency management programs is to make a drug-free, pro-social life-style more rewarding than a drug-using life-style. The community reinforcement approach is a comprehensive contingency management approach that has proven to be extremely helpful in promoting initial abstinence in cocaine addicts.

Once drug use is under control, education and job rehabilitation become crucial. Rewarding life-style options must be found for people in drug recovery to prevent their return to the old environment and way of life.

General Categories of Treatment Programs

Research studies on drug addiction treatment have typically classified treatment programs into several general types or modalities, which are described in the following text. Treatment approaches and individual programs continue to evolve, and many programs in existence today do not fit neatly into traditional drug addiction treatment classifications.

u Agonist Maintenance Treatment for opiate addicts usually is conducted in outpatient settings, often called methadone treatment programs. These programs use a long-acting synthetic opiate medication, usually methadone or LAAM, administered orally for a sustained period at a dosage sufficient to prevent opiate withdrawal, block the effects of illicit opiate use, and decrease opiate craving. Patients stabilized on adequate, sustained dosages of methadone or LAAM can function normally. They can hold jobs, avoid the crime and violence of the street culture, and reduce their exposure to HIV by stopping or decreasing injection drug use and drug-related high-risk sexual behavior.

Patients stabilized on opiate agonists can engage more readily in counseling and other behavioral interventions essential to recovery and rehabilitation. The best, most effective opiate agonist maintenance programs include individual and/or group counseling, as well as provision of, or referral to, other needed medical, psychological, and social services.

Further Reading:

Ball, J.C., and Ross, A. The Effectiveness of Methadone Treatment. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1991.

Cooper, J.R. Ineffective use of psychoactive drugs; Methadone treatment is no exception. JAMA Jan 8; 267(2): 281-282, 1992.

Dole, V.P.; Nyswander, M.; and Kreek, M.J. Narcotic Blockade. Archives of Internal Medicine 118: 304-309, 1996.

Lowinson, J.H.; Payte, J.T.; Joseph, H.; Marion, I.J.; and Dole, V.P. Methadone Maintenance. In: Lowinson, J.H.; Ruiz, P.; Millman, R.B.; and Langrod, J.G., eds. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Baltimore, MD, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1996, pp. 405-414.

McLellan, A.T.; Arndt, I.O.; Metzger, D.S.; Woody, G.E.; and O'Brien, C.P. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA Apr 21; 269(15): 1953-1959, 1993.

Novick, D.M.; Joseph, J.; Croxson, T.S., et al. Absence of antibody to human immunodeficiency virus in long-term, socially rehabilitated methadone maintenance patients. Archives of Internal Medicine Jan; 150(1): 97-99, 1990.

Simpson, D.D.; Joe, G.W.; and Bracy, S.A. Six-year follow-up of opioid addicts after admission to treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry Nov; 39(11): 1318-1323, 1982.

Simpson, D.D. Treatment for drug abuse; Follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Archives of General Psychiatry 38(8): 875-880, 1981.

u Narcotic Antagonist Treatment Using Naltrexone for opiate addicts usually is conducted in outpatient settings although initiation of the medication often begins after medical detoxification in a residential setting. Naltrexone is a long-acting synthetic opiate antagonist with few side effects that is taken orally either daily or three times a week for a sustained period of time. Individuals must be medically detoxified and opiate-free for several days before naltrexone can be taken to prevent precipitating an opiate abstinence syndrome. When used this way, all the effects of self-administered opiates, including euphoria, are completely blocked. The theory behind this treatment is that the repeated lack of the desired opiate effects, as well as the perceived futility of using the opiate, will gradually over time result in breaking the habit of opiate addiction. Naltrexone itself has no subjective effects or potential for abuse and is not addicting. Patient noncompliance is a common problem. Therefore, a favorable treatment outcome requires that there also be a positive therapeutic relationship, effective counseling or therapy, and careful monitoring of medication compliance.

Many experienced clinicians have found naltrexone most useful for highly motivated, recently detoxified patients who desire total abstinence because of external circumstances, including impaired professionals, parolees, probationers, and prisoners in work-release status. Patients stabilized on naltrexone can function normally. They can hold jobs, avoid the crime and violence of the street culture, and reduce their exposure to HIV by stopping injection drug use and drug-related high-risk sexual behavior.

Further Reading

Cornish, J.W.; Metzger, D.; Woody, G.E.; Wilson, D.; McLellan, A.T.; Vandergrift, B.; and O'Brien, C.P. Naltrexone pharmacotherapy for opioid dependent federal probationers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 14(6): 529-534, 1997.

Greenstein, R.A.; Arndt, I.C.; McLellan, A.T.; and O'Brien, C.P. Naltrexone: a clinical perspective. Journal of

Clinical Psychiatry 45 (9 Part 2): 25-28, 1984.

Resnick, R.B.; Schuyten-Resnick, E.; and Washton, A.M. Narcotic antagonists in the treatment of opioid dependence: review and commentary. Comprehensive Psychiatry 20(2): 116-125, 1979.

Resnick, R.B. and Washton, A.M. Clinical outcome with naltrexone: predictor variables and followup status in detoxified heroin addicts. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 311: 241-246, 1978.

Outpatient Drug-Free Treatment varies in the types and intensity of services offered. Such treatment costs less than residential or inpatient treatment and often is more suitable for individuals who are employed or who have extensive social supports. Low-intensity programs may offer little more than drug education and admonition. Other outpatient models, such as intensive day treatment, can be comparable to residential programs in services and effectiveness, depending on the individual patient's characteristics and needs. In many outpatient programs, group counseling is emphasized.

Some outpatient programs are designed to treat patients who have medical or mental health problems in addition to their drug disorder.

Further Reading

Higgins, S.T.; Budney, A.J.; Bickel, W.K.; Foerg, F.E.; Donham, R.; and Badger, G.J. Incentives to improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 51, 568-576, 1994.

Hubbard, R.L.; Craddock, S.G.; Flynn, P.M.; Anderson, J.; and Etheridge, R.M. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11(4): 291-298, 1998.

Institute of Medicine. Treating Drug Problems. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990.

McLellan, A.T.; Grisson, G.; Durell, J.; Alterman, A.I.; Brill, P.; and O'Brien, C.P. Substance abuse treatment in the private setting: Are some programs more effective than others? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 10, 243-254, 1993.

Simpson, D.D. and Brown, B.S. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11(4): 294-307, 1998.

u Long-Term Residential Treatment provides care 24 hours per day, generally in nonhospital settings. The best-known residential treatment model is the therapeutic community (TC), but residential treatment may also employ other models, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. TCs are residential programs with planned lengths of stay of 6 to 12 months. TCs focus on the "resocialization" of the individual and use the program's entire "community," including other residents, staff, and the social context, as active components of treatment. Addiction is viewed in the context of an individual's social and psychological deficits, and treatment focuses on developing personal accountability and responsibility and socially productive lives. Treatment is highly structured and can at times be confrontational, with activities designed to help residents examine damaging beliefs, self-concepts, and patterns of behavior and to adopt new, more harmonious and constructive ways to interact with others. Many TCs are quite comprehensive and can include employment training and other support services on site.

Compared with patients in other forms of drug treatment, the typical TC resident has more severe problems, with more co-occurring mental health problems and more criminal involvement. Research shows that TCs can be modified to treat individuals with special needs, including adolescents, women, those with severe mental disorders, and individuals in the criminal justice system.

Further Reading

Leukefeld, C.; Pickens, R.; and Schuster, C.R. Improving drug abuse treatment: Recommendations for research and practice. In: Pickens, R.W.; Luekefeld, C.G.; and Schuster, C.R., eds. Improving Drug Abuse Treatment, National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph Series, DHHS Pub No. (ADM) 91-1754, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991.

Lewis, B.F.; McCusker, J.; Hindin, R.; Frost, R.; and Garfield, F. Four residential drug treatment programs: Project IMPACT. In: Inciardi, J.A.; Tims, F.M.; and Fletcher, B.W. eds. Innovative Approaches in the Treatment of Drug Abuse. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1993, pp. 45-60.

Sacks, S.; Sacks, J.; DeLeon, G.; Bernhardt, A.; and Staines, G. Modified therapeutic community for mentally ill chemical abusers: Background; influences; program description; preliminary findings. Substance Use and Misuse 32(9); 1217-1259, 1998.

Stevens, S.J., and Glider, P.J. Therapeutic communities: Substance abuse treatment for women. In: Tims, F.M.; De Leon, G.; and Jainchill, N., eds. Therapeutic Community: Advances in Research and Application, National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 144, NIH Pub. No. 94-3633, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1994, pp. 162-180.

Stevens, S.; Arbiter, N.; and Glider, P. Women residents: Expanding their role to increase treatment effectiveness in substance abuse programs. International Journal of the Addictions 24(5): 425-434, 1989.

u Short-Term Residential Programs provide intensive but relatively brief residential treatment based on a modified 12-step approach. These programs were originally designed to treat alcohol problems, but during the cocaine epidemic of the mid-1980's, many began to treat illicit drug abuse and addiction. The original residential treatment model consisted of a 3 to 6 week hospital-based inpatient treatment phase followed by extended outpatient therapy and participation in a self-help group, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Reduced health care coverage for substance abuse treatment has resulted in a diminished number of these programs, and the average length of stay under managed care review is much shorter than in early programs.

Further Reading

Hubbard, R.L.; Craddock, S.G.; Flynn, P.M.; Anderson, J.; and Etheridge, R.M. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11(4): 291-298, 1998.

Miller, M.M. Traditional approaches to the treatment of addiction. In: Graham A.W. and Schultz T.K., eds. Principles of Addiction Medicine, 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Addiction Medicine, 1998.

u Medical Detoxification is a process whereby individuals are systematically withdrawn from addicting drugs in an inpatient or outpatient setting, typically under the care of a physician. Detoxification is sometimes called a distinct treatment modality but is more appropriately considered a precursor of treatment, because it is designed to treat the acute physiological effects of stopping drug use. Medications are available for detoxification from opiates, nicotine, benzodiazepines, alcohol, barbiturates, and other sedatives. In some cases, particularly for the last three types of drugs, detoxification may be a medical necessity, and untreated withdrawal may be medically dangerous or even fatal.

Detoxification is not designed to address the psychological, social, and behavioral problems associated with addiction and therefore does not typically produce lasting behavioral changes necessary for recovery. Detoxification is most useful when it incorporates formal processes of assessment and referral to subsequent drug addiction treatment.

Further Reading

Kleber, H.D. Outpatient detoxification from opiates. Primary Psychiatry 1: 42-52, 1996.

Treating Criminal Justice-Involved Drug Abusers and Addicts

Research has shown that combining criminal justice sanctions with drug treatment can be effective in decreasing drug use and related crime. Individuals under legal coercion tend to stay in treatment for a longer period of time and do as well as or better than others not under legal pressure. Often, drug abusers come into contact with the criminal justice system earlier than other health or social systems, and intervention by the criminal justice system to engage the individual in treatment may help interrupt and shorten a career of drug use. Treatment for the criminal justice-involved drug abuser or drug addict may be delivered prior to, during, after, or in lieu of incarceration.

Prison-based treatment programs

Offenders with drug disorders may encounter a number of treatment options while incarcerated, including didactic drug education classes, self-help programs, and treatment based on therapeutic community or residential milieu therapy models. The TC model has been studied extensively and can be quite effective in reducing drug use and recidivism to criminal behavior. Those in treatment should be segregated from the general prison population, so that the "prison culture" does not overwhelm progress toward recovery. As might be expected, treatment gains can be lost if inmates are returned to the general prison population after treatment. Research shows that relapse to drug use and recidivism to crime are significantly lower if the drug offender continues treatment after returning to the community.

Community-based treatment for criminal justice populations

A number of criminal justice alternatives to incarceration have been tried with offenders who have drug disorders, including limited diversion programs, pretrial release conditional on entry into treatment, and conditional probation with sanctions. The drug court is a promising approach. Drug courts mandate and arrange for drug addiction treatment, actively monitor progress in treatment, and arrange for other services to drug-involved offenders. Federal support for planning, implementation, and enhancement of drug courts is provided under the U.S. Department of Justice Drug Courts Program Office.

As a well-studied example, the Treatment Accountability and Safer Communities (TASC) program provides an alternative to incarceration by addressing the multiple needs of drug-addicted offenders in a community-based setting. TASC programs typically include counseling, medical care, parenting instruction, family counseling, school and job training, and legal and employment services. The key features of TASC include (1) coordination of criminal justice and drug treatment; (2) early identification, assessment, and referral of drug-involved offenders; (3) monitoring offenders through drug testing; and (4) use of legal sanctions as inducements to remain in treatment.

Further Reading

Anglin, M.D. and Hser, Y. Treatment of drug abuse. In: Tonry M. and Wilson J.Q., eds. Drugs and crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990, pp. 393-460.

Hiller, M.L.; Knight, K.; Broome, K.M.; and Simpson, D.D. Compulsory community-based substance abuse treatment and the mentally ill criminal offender. The Prison Journal 76(2), 180-191, 1996.

Hubbard, R.L.; Collins, J.J.; Rachal, J.V.; and Cavanaugh, E.R. The criminal justice client in drug abuse treatment. In Leukefeld C.G. and Tims F.M., eds. Compulsory treatment of drug abuse: Research and clinical practice [NIDA Research Monograph 86]. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998.

Inciardi, J.A.; Martin, S.S.; Butzin, C.A.; Hooper, R.M.; and Harrison, L.D. An effective model of prison-based treatment for drug-involved offenders. Journal of Drug Issues 27 (2): 261-278, 1997.

Wexler, H.K. The success of therapeutic communities for substance abusers in American prisons. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 27(1): 57-66, 1997.

Wexler, H.K. Therapeutic communities in American prisons. In Cullen, E.; Jones, L.; and Woodward R., eds. Therapeutic Communities in American Prisons. New York: Wiley and Sons, 1997.

Wexler, H.K.; Falkin, G.P.; and Lipton, D.S. (1990). Outcome evaluation of a prison therapeutic community for substance abuse treatment. Criminal Justice and Behavior 17(1): 71-92, 1990.

v Scientifically Based Approaches to Drug Addiction Treatment

This section presents several examples of treatment approaches and components that have been developed and tested for efficacy through research supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Each approach is designed to address certain aspects of drug addiction and its consequences for the individual, family, and society. The approaches are to be used to supplement or enhance not replace existing treatment programs.

This section is not a complete list of efficacious, scientifically based treatment approaches. Additional approaches are under development as part of NIDA's continuing support of treatment research.

uRelapse Prevention , a cognitive-behavioral therapy, was developed for the treatment of problem drinking and adapted later for cocaine addicts. Cognitive-behavioral strategies are based on the theory that learning processes play a critical role in the development of maladaptive behavioral patterns. Individuals learn to identify and correct problematic behaviors. Relapse prevention encompasses several cognitive-behavioral strategies that facilitate abstinence as well as provide help for people who experience relapse.

The relapse prevention approach to the treatment of cocaine addiction consists of a collection of strategies intended to enhance self-control. Specific techniques include exploring the positive and negative consequences of continued use, self-monitoring to recognize drug cravings early on and to identify high-risk situations for use, and developing strategies for coping with and avoiding high-risk situations and the desire to use. A central element of this treatment is anticipating the problems patients are likely to meet and helping them develop effective coping strategies.

Research indicates that the skills individuals learn through relapse prevention therapy remain after the completion of treatment. In one study, most people receiving this cognitive-behavioral approach maintained the gains they made in treatment throughout the year following treatment.

References

Carroll, K.; Rounsaville, B.; and Keller, D. Relapse prevention strategies for the treatment of cocaine abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 17(3): 249-265, 1991.

Carroll, K.; Rounsaville, B.; Nich, C.; Gordon, L.; Wirtz, P.; and Gawin, F. One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry 51: 989-997, 1994.

Marlatt, G. and Gordon, J.R., eds. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press, 1985.

u Supportive-Expressive Psychotherapy is a time-limited, focused psychotherapy that has been adapted for heroin- and cocaine-addicted individuals. The therapy has two main components:

Supportive techniques to help patients feel comfortable in discussing their personal experiences.

Expressive techniques to help patients identify and work through interpersonal relationship issues.

Special attention is paid to the role of drugs in relation to problem feelings and behaviors, and how problems may be solved without recourse to drugs.

The efficacy of individual supportive-expressive psychotherapy has been tested with patients in methadone maintenance treatment who had psychiatric problems. In a comparison with patients receiving only drug counseling, both groups fared similarly with regard to opiate use, but the supportive-expressive psychotherapy group had lower cocaine use and required less methadone. Also, the patients who received supportive-expressive psychotherapy maintained many of the gains they had made. In an earlier study, supportive-expressive psychotherapy, when added to drug counseling, improved outcomes for opiate addicts in methadone treatment with moderately severe psychiatric problems.

References

Luborsky, L. Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive-Expressive (SE) Treatment. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Woody, G.E.; McLellan, A.T.; Luborsky, L.; and O'Brien, C.P. Psychotherapy in community methadone programs: a validation study. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(9): 1302-1308, 1995.

Woody, G.E.; McLellan, A.T.; Luborsky, L.; and O'Brien, C.P. Twelve month follow-up of psychotherapy for opiate dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 144: 590-596, 1987.

u Individualized Drug Counseling focuses directly on reducing or stopping the addict's illicit drug use. It also addresses related areas of impaired functioning such as employment status, illegal activity, family/social relations as well as the content and structure of the patient's recovery program. Through its emphasis on short-term behavioral goals, individualized drug counseling helps the patient develop coping strategies and tools for abstaining from drug use and then maintaining abstinence. The addiction counselor encourages 12-step participation and makes referrals for needed supplemental medical, psychiatric, employment, and other services. Individuals are encouraged to attend sessions one or two times per week.

In a study that compared opiate addicts receiving only methadone to those receiving methadone coupled with counseling, individuals who received only methadone showed minimal improvement in reducing opiate use. The addition of counseling produced significantly more improvement. The addition of onsite medical/psychiatric, employment, and family services further improved outcomes.

In another study with cocaine addicts, individualized drug counseling, together with group drug counseling, was quite effective in reducing cocaine use. Thus, it appears that this approach has great utility with both heroin and cocaine addicts in outpatient treatment.

References

McLellan, A.T.; Arndt, I.; Metzger, D.S.; Woody, G.E.; and O'Brien, C.P. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association 269(15): 1953-1959, 1993.

McLellan, A.T.; Woody, G.E.; Luborsky, L.; and O'Brien, C.P. Is the counselor an `active ingredient' in substance abuse treatment? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 176: 423-430, 1988.

Woody, G.E.; Luborsky, L.; McLellan, A.T.; O'Brien, C.P.; Beck, A.T.; Blaine, J.; Herman, I.; and Hole, A. Psychotherapy for opiate addicts: Does it help? Archives of General Psychiatry 40: 639-645, 1983.

Crits-Cristoph, P.; Siqueland, L.; Blaine, J.; Frank, A.; Luborsky, L.; Onken, L.S.; Muenz, L.; Thase, M.E.; Weiss, R.D.; Gastfriend, D.R.; Woody, G.; Barber, J.P.; Butler, S.F.; Daley, D.; Bishop, S.; Najavits, L.M.; Lis, J.; Mercer, D.; Griffin, M.L.; Moras, K.; and Beck, A. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: Results of the NIDA Cocaine Collaborative Study. Archives of General Psychiatry (in press).

u Motivational Enhancement Therapy is a client-centered counseling approach for initiating behavior change by helping clients to resolve ambivalence about engaging in treatment and stopping drug use. This approach employs strategies to evoke rapid and internally motivated change in the client, rather than guiding the client stepwise through the recovery process. This therapy consists of an initial assessment battery session, followed by two to four individual treatment sessions with a therapist. The first treatment session focuses on providing feedback generated from the initial assessment battery to stimulate discussion regarding personal substance use and to elicit self-motivational statements. Motivational interviewing principles are used to strengthen motivation and build a plan for change. Coping strategies for high-risk situations are suggested and discussed with the client. In subsequent sessions, the therapist monitors change, reviews cessation strategies being used, and continues to encourage commitment to change or sustained abstinence. Clients are sometimes encouraged to bring a significant other to sessions. This approach has been used successfully with alcoholics and with marijuana-dependent individuals.

References

Budney, A.J.; Kandel, D.B.; Cherek, D.R.; Martin, B.R.; Stephens, R.S.; and Roffman, R. College on problems of drug dependence meeting, Puerto Rico (June 1996). Marijuana use and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 45: 1-11, 1997.

Miller, W.R. Motivational interviewing: research, practice and puzzles. Addictive Behaviors 61(6): 835-842, 1996.

Stephens, R.S.; Roffman, R.A.; and Simpson, E.E. Treating adult marijuana dependence: a test of the relapse prevention model. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 62: 92-99, 1994.

uBehavioral Therapy for Adolescents incorporates the principle that unwanted behavior can be changed by clear demonstration of the desired behavior and consistent reward of incremental steps toward achieving it. Therapeutic activities include fulfilling specific assignments, rehearsing desired behaviors, and recording and reviewing progress, with praise and privileges given for meeting assigned goals. Urine samples are collected regularly to monitor drug use. The therapy aims to equip the patient to gain three types of control:

Stimulus control helps patients avoid situations associated with drug use and learn to spend more time in activities incompatible with drug use.

Urge control helps patients recognize and change thoughts, feelings, and plans that lead to drug use.

Social control involves family members and other people important in helping patients avoid drugs. A parent or significant other attends treatment sessions when possible and assists with therapy assignments and reinforcing desired behavior.

According to research studies, this therapy helps adolescents become drug free and increases their ability to remain drug free after treatment ends. Adolescents also show improvement in several other areas, such as employment/school attendance, family relationships, depression, institutionalization, and alcohol use. Such favorable results are attributed largely to including family members in therapy and rewarding drug abstinence as verified by urinalysis.

References

Azrin, N.H.; Acierno, R.; Kogan, E.; Donahue, B.; Besalel, V.; and McMahon, P.T. Follow-up results of supportive versus behavioral therapy for illicit drug abuse. Behavioral Research & Therapy 34(1): 41-46, 1996.

Azrin, N.H.; McMahon, P.T.; Donahue, B.; Besalel, V.; Lapinski, K.J.; Kogan, E.; Acierno, R.; and Galloway, E. Behavioral therapy for drug abuse: a controlled treatment outcome study. Behavioral Research & Therapy 32(8): 857-866, 1994.

Azrin, N.H.; Donohue, B.; Besalel, V.A.; Kogan, E.S.; and Acierno, R. Youth drug abuse treatment: A controlled outcome study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 3(3): 1-16, 1994.

u Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) for Adolescents is an outpatients family-based drug abuse treatment for teenagers. MDFT views adolescent drug use in terms of a network of influences (that is, individual, family, peer, community) and suggests that reducing unwanted behavior and increasing desirable behavior occur in multiple ways in different settings. Treatment includes individual and family sessions held in the clinic, in the home, or with family members at the family court, school, or other community locations.

During individual sessions, the therapist and adolescent work on important developmental tasks, such as developing decisionmaking, negotiation, and problem-solving skills. Teenagers acquire skills in communicating their thoughts and feelings to deal better with life stressors, and vocational skills. Parallel sessions are held with family members. Parents examine their particular parenting style, learning to distinguish influence from control and to have a positive and developmentally appropriate influence on their child.

References

Diamond, G.S., and Liddle, H.A. Resolving a therapeutic impasse between parents and adolescents in Multi-dimensional Family Therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64(3): 481-488, 1996.

Schmidt, S.E.; Liddle, H.A.; and Dakof, G.A. Effects of multidimensional family therapy: Relationship of changes in parenting practices to symptom reduction in adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Family Psychology 10(1): 1-16, 1996.

u Multisystemic Therapy (MST) addresses the factors associated with serious antisocial behavior in children and adolescents who abuse drugs. These factors include characteristics of the adolescent (for example, favorable attitudes toward drug use), the family (poor discipline, family conflict, parental drug abuse), peers (positive attitudes toward drug use), school (dropout, poor performance), and neighborhood (criminal subculture). By participating in intense treatment in natural environments (homes, schools, and neighborhood settings) most youths and families complete a full course of treatment. MST significantly reduces adolescent drug use during treatment and for at least 6 months after treatment. Reduced numbers of incarcerations and out-of-home placements of juveniles offset the cost of providing this intensive service and maintaining the clinicians' low caseloads.

References

Henggeler, S.W.; Pickrel, S.G.; Brondino, M.J.; and Crouch, J.L. Eliminating (almost) treatment dropout of substance abusing or dependent delinquents through home-based multisystemic therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 153: 427-428, 1996.

Henggeler, S.W.; Schoenwald, S.K.; Borduin, C.M.; Rowland, M.D.; and Cunningham, P. B. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press, 1998.

Schoenwald, S.K.; Ward, D.M.; Henggeler, S.W.; Pickrel, S.G.; and Patel, H. MST treatment of substance abusing or dependent adolescent offenders: Costs of reducing incarceration, inpatient, and residential placement. Journal of Child and Family Studies 5: 431-444, 1996.

u Combined Behavioral and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Nicotine Addiction

consists of two main components:

The transdermal nicotine patch or nicotine gum reduces symptoms of withdrawal, producing better initial abstinence.

The behavioral component concurrently provides support and reinforcement of coping skills, yielding better long-term outcomes.

Through behavioral skills training, patients learn to avoid high-risk situations for smoking relapse early on and later to plan strategies to cope with such situations. Patients practice skills in treatment, social, and work settings. They learn other coping techniques, such as cigarette refusal skills, assertiveness, and time management. The combined treatment is based on the rationale that behavioral and pharmacological treatments operate by different yet complementary mechanisms that produce potentially additive effects.

References

Fiore, M.C.; Kenford, S.L.; Jorenby, D.E.; Wetter, D.W.; Smith, S.S.; and Baker, T.B. Two studies of the clinical effectiveness of the nicotine patch with different counseling treatments. Chest 105: 524-533, 1994.

Hughes, J.R. Combined psychological and nicotine gum treatment for smoking: a critical review. Journal of Substance Abuse 3: 337-350, 1991.

American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Nicotine Dependence. American Psychiatric Association, 1996.

u Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) Plus Vouchers

Is an intensive 24-week outpatient therapy for treatment of cocaine addiction. The treatment goals are twofold:

To achieve cocaine abstinence long enough for patients to learn new life skills that will help sustain abstinence.

To reduce alcohol consumption for patients whose drinking is associated with cocaine use.

Patients attend one or two individual counseling sessions per week, where they focus on improving family relations, learning a variety of skills to minimize drug use, receiving vocational counseling, and developing new recreational activities and social networks. Those who also abuse alcohol receive clinic-monitored disulfiram (Antabuse) therapy. Patients submit urine samples two or three times each week and receive vouchers for cocaine-negative samples. The value of the vouchers increases with consecutive clean samples. Patients may exchange vouchers for retail goods that are consistent with a cocaine-free life-style.

This approach facilitates patients' engagement in treatment and systematically aids them in gaining substantial periods of cocaine abstinence. The approach has been tested in urban and rural areas and used successfully in outpatient detoxification of opiate-addicted adults and with inner-city methadone maintenance patients who have high rates of intravenous cocaine abuse.

References

Higgins, S.T.; Budney, A.J.; Bickel, H.K.; Badger, G.; Foerg, F.; and Ogden, D. Outpatient behavioral treatment for cocaine dependence: one-year outcome. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology 3(2): 205-212, 1995.

Higgins, S.T.; Budney, A.J.; Bickel, W.K.; Foerg, F.; Donham, R.; and Badger, G. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 51: 568-576, 1994.

Silverman, K.; Higgins, S.T.; Brooner, R.K.; Montoya, I.D.; Cone, E.J.; Schuster, C.R.; and Preston, K.L. Sustained cocaine abstinence in methadone maintenance patients through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 53: 409-415, 1996.

u Voucher-Based Reinforcement Therapy in Methadone Maintenance Treatment

Helps patients achieve and maintain abstinence from illegal drugs by providing them with a voucher each time they provide a drug-free urine sample. The voucher has monetary value and can be exchanged for goods and services consistent with the goals of treatment. Initially, the voucher values are low, but their value increases with the number of consecutive drug-free urine specimens the individual provides. Cocaine- or heroin-positive urine specimens reset the value of the vouchers to the initial low value. The contingency of escalating incentives is designed specifically to reinforce periods of sustained drug abstinence.

Studies show that patients receiving vouchers for drug-free urine samples achieved significantly more weeks of abstinence and significantly more weeks of sustained abstinence than patients who were given vouchers independent of urinalysis results. In another study, urinalyses positive for heroin decreased significantly when the voucher program was started and increased significantly when the program was stopped.

References

Silverman, K.; Higgins, S.; Brooner, R.; Montoya, I.; Cone, E.; Schuster, C.; and Preston, K. Sustained cocaine abstinence in methadone maintenance patients through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 53: 409-415, 1996.

Silverman, K.; Wong, C.; Higgins, S.; Brooner, R.; Montoya, I.; Contoreggi, C.; Umbricht-Schneiter, A.; Schuster, C.; and Preston, K. Increasing opiate abstinence through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 41: 157-165, 1996.

u Day Treatment With Abstinence Contingencies and Vouchers was developed to treat homeless crack addicts. For the first 2 months, participants must spend 5.5 hours daily in the program, which provides lunch and transportation to and from shelters. Interventions include individual assessment and goal setting, individual and group counseling, multiple psychoeducational groups (for example, didactic groups on community resources, housing, cocaine, and HIV/AIDS prevention; establishing and reviewing personal rehabilitation goals; relapse prevention; weekend planning), and patient-governed community meetings during which patients review contract goals and provide support and encouragement to each other. Individual counseling occurs once a week, and group therapy sessions are held three times a week. After 2 months of day treatment and at least 2 weeks of abstinence, participants graduate to a 4-month work component that pays wages that can be used to rent inexpensive, drug-free housing. A voucher system also rewards drug-free related social and recreational activities.

This innovative day treatment was compared with treatment consisting of twice-weekly individual counseling and 12-step groups, medical examinations and treatment, and referral to community resources for housing and vocational services. Innovative day treatment followed by work and housing dependent upon drug abstinence had a more positive effect on alcohol use, cocaine use, and days homeless.

References

Milby, J.B.; Schumacher, J.E.; Raczynski, J.M.; Caldwell, E.; Engle, M.; Michael, M.; and Carr, J. Sufficient conditions for effective treatment of substance abusing homeless. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 43: 39-47, 1996.

Milby, J.B.; Schumacher, J.E.; McNamara, C.; Wallace, D.; McGill, T.; Stange, D.; and Michael, M. Abstinence contingent housing enhances day treatment for homeless cocaine abusers. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph Series 174, Problems of Drug Dependence: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Scientific Meeting. The College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc., 1996.

u The Matrix Model provides a framework for engaging stimulant abusers in treatment and helping them achieve abstinence. Patients learn about issues critical to addiction and relapse, receive direction and support from a trained therapist, become familiar with self-help programs, and are monitored for drug use by urine testing. The program includes education for family members affected by the addiction.

The therapist functions simultaneously as teacher and coach, fostering a positive, encouraging relationship with the patient and using that relationship to reinforce positive behavior change. The interaction between the therapist and the patient is realistic and direct but not confrontational or parental. Therapists are trained to conduct treatment sessions in a way that promotes the patient's self-esteem, dignity, and self-worth. A positive relationship between patient and therapist is a critical element for patient retention.

Treatment materials draw heavily on other tested treatment approaches. Thus, this approach includes elements pertaining to the areas of relapse prevention, family and group therapies, drug education, and self-help participation. Detailed treatment manuals contain work sheets for individual sessions; other components include family educational groups, early recovery skills groups, relapse prevention groups, conjoint sessions, urine tests, 12-step programs, relapse analysis, and social support groups.

A number of projects have demonstrated that participants treated with the Matrix model demonstrate statistically significant reductions in drug and alcohol use, improvements in psychological indicators, and reduced risky sexual behaviors associated with HIV transmission. These reports, along with evidence suggesting comparable treatment response for methamphetamine users and cocaine users and demonstrated efficacy in enhancing naltrexone treatment of opiate addicts, provide a body of empirical support for the use of the model.

References

Huber, A.; Ling, W.; Shoptaw, S.; Gulati, V.; Brethen, P.; and Rawson, R. Integrating treatments for methamphetamine abuse: A psychosocial perspective. Journal of Addictive Diseases 16: 41-50, 1997.

Rawson, R.; Shoptaw, S.; Obert, J.L.; McCann, M.; Hasson, A.; Marinelli-Casey, P.; Brethen, P.; and Ling, W. An intensive outpatient approach for cocaine abuse: The Matrix model. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 12(2): 117-127, 1995.

v Rate and Duration of Drug Activity Play Major Roles in Drug Abuse, Addiction, and Treatment

When smoked or taken intravenously, cocaine produces a fast, intense high that dissipates quickly, creating a powerful need to take the drug again. In this regard, cocaine provides a perfect illustration of the critical role that a compound's rate and duration of action play in drug abuse and addiction.

Rate of Action