Figure 1

| Contents | Previous | Post-Test |

The demand for fixed prosthodontics has increased significantly over the past 40 years. This increased demand is related to the fact that more people than ever are retaining their natural teeth, and these people are living a longer life span. Over the years teeth that have served a very useful function become discolored, break off, wear down or crack, require periodontal and endodontical treatment, and in general need large restorations and crowns or bridges.

This trend toward retaining natural teeth through the end of life is only likely to become more pronounced. Social, educational and environmental factors are clearly at work. Children and adults are more educated about oral hygiene. Educational campaigns promoting dental health and hygiene have taken roots in schools, workplaces and media. An overwhelming part of the population now receives fluoride in toothpaste, rinses and water supplies. People are eating more natural and healthy foods. All of these factors have contributed to the increase in the demand for fixed prosthodontics.

Along with the increase in the need and demand for fixed prosthodontics there has been a parallel increase in the quality of prosthodontics expected by the patient. Good prosthodontic treatment can transform an unhealthy, unattractive dentition with poor function, into a comfortable, healthy occlusion capable of giving years of further service while greatly enhancing aesthetics. Dental profession faces a challenge in that it is called upon to plan complex treatment, provide restorations that will serve the patient for a number of years, evaluate various prostheses to meet the patient's needs, and choose from a variety of new materials and new devices. This requires meticulous attention to every detail from the initial patient interview through the active treatment phases to a planned schedule of follow-up care.

Patient history and examination are two important steps that should be given proper consideration before initiating any prosthetic treatment.

Chief complaint. Determine the primary reason for seeking treatment which would usually fall into one of the following four categories:

Dental History - This should include all of the following treatments that the patient may have received:

The history-taking-step should be followed by a thorough examination which would consist of all of the following steps:

Fixed prosthesis. A fixed prosthesis is any of a variety of replacements for a missing tooth or a part of a tooth that a dentist cements in place and one the patient cannot remove. Restoration such as inlays, pinledge castings, onlays, crowns, and fixed partial dentures fall into this category. A fixed prosthesis may be constructed entirely from a cast metal alloy, from acrylic resin, or from porcelain. Frequently, a fixed prosthesis is made out of a combination of these materials (for example a complete crown that has a metal substructure and a porcelain veneer).

Die. A die is a positive reproduction of a prepared tooth, made from a suitable, hard substance (improved artificial stone or metal). A die can be constructed from a complete arch, partial arch, or individual tooth impression. Most pf the fixed prostheses are made by the indirect method. The dentist uses the direct method when carving the form of the restoration on the natural tooth in the patient's mouth. The dentist or technician uses the indirect method when forming the shape of the restoration outside of the mouth on a die. Because there is such overwhelming dependence on dies in fixed prosthetic dentistry, a die has to be extraordinarily accurate. And methods of maintaining the positions of dies on casts must be perfectly dependable.

Wax pattern. With the exception of complete porcelain or complete resin restorations, at least part of a fixed prosthesis is cast in metal. Castings are made from wax patterns. A pattern is an exact wax replica of a desired shape. When- the wax pattern is invested and burned out a casting can be made in the resultant mold. If the dentist carves the pattern wax in the patient's mouth, it is a direct pattern. Small inlays and complete crown cores are sometimes done this way. If the dentist adapts and carves the pattern on a die, it is an indirect pattern.

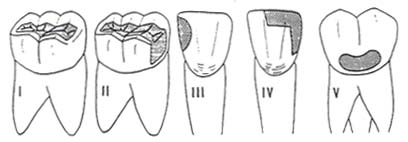

Inlays. An inlay is a dental restoration that fits into a prepared cavity and is held there by its precision fit and by a cementing medium. Because inlays are, for the most part, surrounded by intact tooth structure, they are often called intracoronal restorations. The various forms of inlays are primarily used to restore individual tooth contours and function: In the majority of cases, an inlay is not a suitable anchor casting (retainer) for a fixed partial denture. Inlays are usually cast in medium hard gold, but can be made of other materials (porcelain). There are five classes of inlays, based on the location of the surfaces being restored (Fig. 1)

|

|

|

Figure 1 |

(a) Class I. Located on the occlusal surfaces of bicuspids or molars.

(b) Class II. Located on an occlusal surfaces combined with one or both proximal surfaces.

(c) Class III. Made for the mesial or distal surfaces of anterior teeth. They do not involve incisal angles.

(d) Class IV. Made for the mesial and distal surface of an anterior tooth plus one or both of its incisal angles.

(e) Class V. Limited to the facial surface of any of the teeth.

| A more specific way of naming an inlay is to cite the tooth surfaces it restores. As examples: MO (Mesio-Occlusal) inlay; MOD (Mesio-Occ1usol-Distal) inlay (Fig. 2); DI (Distal-Incisal) inlay; MID (Mesio-Inciso-Distal) inlay. |

|

|

Figure 2 |

|

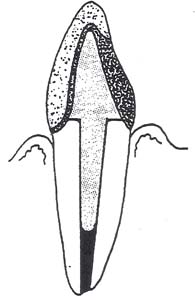

| Pinledges. A pinledge is a thin, cast gold restoration that covers the lingual and one proximal surface of an anterior tooth (Fig. 3). It is usually categorized as a specialized form of inlay. The feature that distinguishes it from a conventional inlay is that it has two or three parallel pins, about 1.5 to 2 mm long, that penetrate the lingual dentin for retention. The thinness of the casting and the small diameter of the pins require that the pinledge be constructed of a hard gold alloy (Type III gold). A pinledge is the most esthetic and the most -conservative type of casting used in the anterior region as a fixed partial denture retainer. It is also the least reliable and most potentially destructive to an abutment tooth. A pin ledge functions best as filling for a cavity and should not ordinarily be expected to do more. |

|

|

Figure 3 |

Onlays. Onlays are cast gold restorations that ordinarily cover the mesial, occlusal, and distal surfaces (MOD) of posterior teeth. Onlays differ from inlays in this respect. An onlay covers the entire occlusal surface of a tooth to include the cusps. An onlay is the smallest of the fixed prosthethic restorations classified as extracoronal. Whereas an intracoronal replacement like an inlay fits into a tooth, an extracoronal restoration fits around what remains of a tooth. Many dentists maintain that an onlay is the minimum restoration adequate to act as a fixed partial denture retainer.

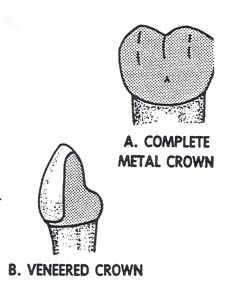

Artificial Crowns. An artificial crown is a fixed prosthetic restoration which covers more than half of the tooth's surface that is exposed to view in the patient's mouth. Onlays are classified as extracoronal restoration, and the various kinds of crowns make up the balance of extracoronal category:

(a) Complete Crown. A complete crown covers the entire surface anatomy of a tooth's clinical crown:

|

|

|

| Figure 4A & Figure 4B |

Figure 5 |

(b) Partial Crown. A crown made entirely from metal that covers more than half and less than all of the tooth's clinical crown. A partial crown is named according to the fractional amount of the clinical crown it covers. Examples are: the half, the three-quarter, the four-fifths, and the seven-eighths crowns (Fig. 4C and 4D).

|

|

|

|

Figure4C |

Figure4D |

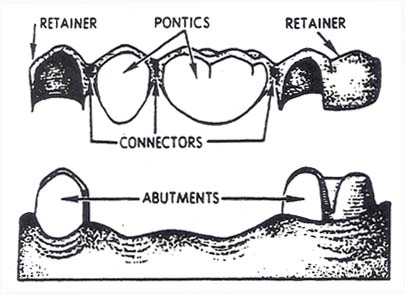

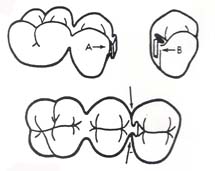

Fixed Partial Denture. A fixed partial denture is a restoration designed to replace one or more missing natural teeth. In contrast to a removable partial denture, the dentist attaches a fixed partial denture to natural teeth or roots by cementation. A primary abutment is a tooth or root used for support and anchorage of one of the ends of a fixed partial denture. An intermediate abutment is a tooth without other natural teeth in proxi-mal contact, situated between two primary abutments. The typical fixed partial denture consists of these pans (Fig. 6):

| (a) Retainers. A retainer is a casting that the dentist attaches to an abutment tooth to secure and support fixed partial denture's artificial tooth or teeth. (b) Pontics. Pontic is the general name for any artificial tooth suspended from a retainer. Pontics are classified according to the kinds of materials used to make them, and according to the way they relate to gingival tissue under them (gingival adaptation): |

|

|

Figure 6 |

a. Complete Metal Pontic. Use of these pontics is limited to the posterior areas of the mouth where they are not likely to be seen.

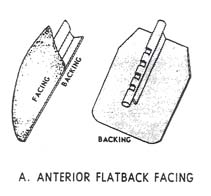

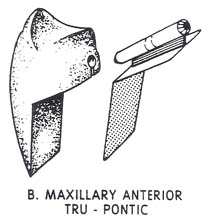

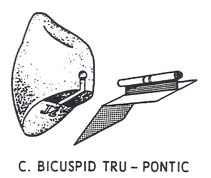

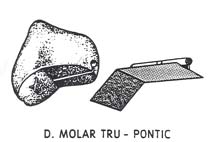

b. Cast Metal Combined with a Prefabricated Resin or Porcelain Blank (Fig. 7) ..The blanks are commercially available in anterior and posterior tooth forms, and in a selection of sizes and shades. The dentist selects an appropriate blank and custom grinds it to fit an edentulous space. The rest of the artificial tooth, whether it be backing for an anterior or an occlusal surface for a posterior, is waxed and cast in metal. The dentist then cements the modified resin or porcelain blank to its retaining post on the metal casting

c. Veneered Pontic. The majority of the pontic's substructure is cast metal, and the balance consists of a layer of acrylic resin or porcelain processed onto it. Acrylic veneers are mechanically retained by incorporating retention beads or loops into the casting. Porcelain is retained by baking and fusing it directly to the metal substructure. The tip of a pontic is usually made to contact gingival tissue. If the part of a pontic that contacts gingival is made from a material that is chemically active or collects debris, inflammation will probably result. Glazed porcelain and highly polished gold provoke minimal tissue reaction. Acrylic resin is second best. Food tends to stick more to a plastic surface, bacteria grow in the debris, and produce toxic products that irritate tissue. In time, resin will absorb oral fluids and acquire an unpleasant odor.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 7 |

||

a. Modified Ridgelap Pontic

b. "Egg" Shape in Contact with a Residual Ridge

c. Hygienic Pontic (Conventional or Modified)

| (c) Connectors. A connector is that part of a fixed partial denture that unites a pontic to a retainer or joins pontics together. Connectors are classified as rigid (soldered joint) or nonrigid (these key-to-keyway arrangements are known as semiprecision attachments). The term stress breaker is commonly applied to nonrigid connectors (Fig. 8). Rigid connectors are by far the most popular option. There are problem Figure 8 situations where a stress-broken fixed partial denture is the restoration of choice. A stress-broken joint is indicated when there is no common path of insertion for the retainers, or when a fixed partial denture includes an intermediate abutment. |

|

| Figure 8 |

Fixed Splints. There are ways to make a number of teeth share a load being placed on one of them. This helps to prolong the life of teeth that are loose or which have lost supporting bone. Stabilizing a mobile tooth or teeth is called splinting. When stabilizing a tooth from adjacent, connected castings that have been cemented to place in the mouth, it becomes a form fixed splinting. Such splints are made in the same way as a fixed partial denture. The only difference is that there are no pontics involved.

NOTE: The overall size of fixed partial dentures and fixed splints is expressed in units. Each replacement tooth or retainer counts as a unit. For example, a fixed partial denture with three retainers and two pontics has 5 units, and a fixed splint with four castings has 4 units.

Interim Fixed Partial Denture This is a rigid, temporary restoration that replaces missing teeth and is generally made from self-curing resin. Its purpose is to protect cut tooth surfaces and hold the abutment teeth in position while the definitive fixed partial denture is being made.

Production of a fixed, cast restoration usually follows this progression: